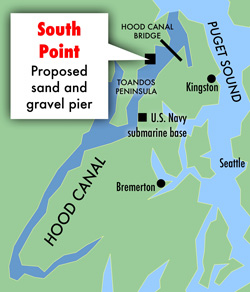

Fred Hill Materials, a Poulsbo-based gravel company, wants to bring the mountain to Mohammed. The company proposes to expand a modest mining operation to meet demand for gravel that is fueled by the explosive pace of West Coast development. Fred Hill wants to construct a four-mile conveyor belt connecting a sprawling gravel mine inland to a 1,100-foot, nine-story-high pier and 900-foot moorage dock. The shipping facility would be on the west shore of the canal, five miles south of the Highway 104 Hood Canal Bridge.

When fully operational, the “pit to pier” operation would mine, transport, and ship an estimated 60,000 tons of gravel 24 hours a day, loading into barges and ships bound for domestic and foreign ports. Each vessel would have to negotiate a dicey passage under or through the opening of the floating Hood Canal Bridge. Cost of the project is estimated at $15 million.

A family-owned company, Fred Hill Materials likes to think big. With construction of the Trident Submarine Base at Bangor in the 1970s and 1980s, the company expanded its truck fleet from seven to 80. Government contracts for an aircraft carrier dock at Bremerton and a replacement Hood Canal Bridge have bolstered its fortunes. Now the company wants to break out of the local market and go coastal, possibly global.

It’s off to a good start. Fred Hill just negotiated the initial leg of a projected three- to five-year permitting process. In a decision finalized July 7, in spite of vigorous local opposition, Jefferson County’s three commissioners unanimously approved a zoning change that allows the company to mine 690 acres of private forest. In their rush to accommodate the development, the commissioners claimed the mining rezone was unrelated to the pit-to-pier project. Opponents promise the decision will weigh heavily this fall when two of the three Republican commissioners stand for re-election.

With a score of state and federal permits still needed, it won’t all be smooth sailing for the would-be gravel giant. The company has allocated $3 million to see the project through its permitting phase. But several recent developments suggest rough seas ahead. This past winter, the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, whose Point No Point treaty area includes upper Hood Canal, announced its opposition to the project. Its fellow treaty signer, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, followed suit.

More worrisome to the company, U.S. Rep. Norm Dicks of Bremerton, the powerful ranking Democrat on the House Appropriations Committee, made it known that he thinks the project is just too big. In May, he wrote the Jefferson County commissioners opposing the zoning change, stating that the project would unalterably change the character of Hood Canal. He promised his constituents, “I will do what I can to oppose it.” Add these influential voices to the activist members of the Hood Canal Coalition, a group formed in 2002 to fight the development, and Fred Hill’s seas assume tsunami proportions.

The tribes’ concerns center around treaty rights. Tribal members question the appropriateness of industrial-scale development on one of the most biologically productive and undisturbed corners of Puget Sound. Says Ron Charles, chairman of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe: “The effects of Fred Hill’s project on Hood Canal’s fragile ecology would jeopardize the tribe’s treaty-reserved hunting and fishing rights. The impacts from the project are simply too great.”

Charles points not only to the pier and loading facility but to the upland mining operation in the Thorndike Creek watershed. Mining activity will remove material down to within 10 feet of the aquifer. “This is a groundwater-fed system and one of the most pristine salmon streams left in Puget Sound,” Charles says. “To the tribe, the mining expansion is as much a concern as the shoreline development.”

Biologists have identified the proposed pier site as important habitat for forage fish, the small sand lance and surf smelt that feed salmon. Adjacent eelgrass beds are nurseries for young salmon, and nearby shellfish beds and crabbing grounds are critical resources for the tribe. Hood Canal produces some $7 million in commercial shellfish annually, and 80 percent to 90 percent of tribal households rely on shellfish and salmon for subsistence or part of their livelihoods. Potential harm caused by invasive species introduced by ship ballast water or from hulls could be devastating.

Washington has designated Hood Canal a “shoreline of statewide significance.” Given the worsening water quality in the southern canal, tribal people are particularly sensitive to new developments that might further degrade Hood Canal’s overall health, Charles says. “These are all valid concerns,” admits Dan Baskins, pit-to-pier project manager for Fred Hill Materials, “but mitigation will cover them.”

Baskins ticks off the safety measures that would be in place to ensure that no harm would come to the canal or its resources: There would be no fueling at the dock; a tender tug and boom would contain any incidental spills. U.S.–flagged container ships would not be available for a decade, and tugs don’t use ballast water, so invasive species don’t pose an immediate threat. Tugs themselves are extremely safe. “They’re the vessels that rescue other boats that get into trouble,” he notes. “And if we spill sand and gravel, it would be beneficial. It’s the same stuff that’s needed to restore Puget Sound beaches.”

The company has made much of its proposed donation of thousands of tons of sand for beach restoration, a claim dismissed by opponents of the project who say that shoreline restoration means removing bulkheads, not building new industrial facilities.

Baskins is more comfortable discussing gravel. He says each one of us in Washington accounts for 12.7 tons of gravel use each year. In 2000, Washington consumed 80 million tons. By 2020, projected consumption will climb to slightly more than 100 million tons. Gravel mines make controversial neighbors—particularly in the urbanizing areas of Puget Sound—and additional truck traffic snarls highways, takes a toll on road surfaces, and pollutes.

According to Baskins, marine transport in barges and ships is far and away the safest, most cost-effective, and environmentally sound mode of gravel transport. And Fred Hill, with its admirable environmental record and generous treatment of its union employees, he says, is the company to do it.

Even the project’s strongest critics concede the company has been an exemplary neighbor. And the promise of 30 new union-wage jobs in an area of chronic underemployment has secured unwavering union support. But the unions have been pointedly unsuccessful in convincing their local Jefferson and Clallam county Democratic parties to embrace the proposal; both adopted platform planks opposing it.

With the notable exception of local elected officials, unions, and business groups, opposition in the normally pro-development rural peninsula counties has been overwhelming. The Hood Canal Coalition currently boasts 2,400 members and 55 supporting organizations.

John Fabian, a spokesperson for the coalition, isn’t buying any of Fred Hill’s claims. He says the project is out of scale with the rural character of the waterway and presents unacceptable risks to the environment, safety, and public health.

“Fred Hill says all the barge traffic will go underneath the bridge, but we find that to be a preposterous claim,” Fabian says. Bridge openings to accommodate large vessels bring traffic on state Route 104 to a halt. “We see 300-ton barges going through the [open] bridge now in rough weather, and Fred Hill is talking about barges up to 20,000 tons.” The conveyor will be capable of delivering three times that amount, or 60,000 tons a day. When bulk carrier ships come on line, the company projects six to 12 bridge openings a month, all during early hours.

But disruption of traffic from bridge openings seems minor compared to the specter of long-term bridge closure in the event of a collision. The economic blow to the peninsula’s economy would be devastating. “To be honest, I’m not sure which could be worse,” says Fabian, “several openings a day or running the risk of a barge hitting the bridge.”

As far as economic benefits to local counties, Fabian sees only costs. And he has little faith that Jefferson County’s current commissioners will give the project the critical review it needs.

For the company’s part, Baskins is sanguine. With a well-financed permitting program and no objections from local pols or state legislators, he seems undeterred by opposing views. “I’m a big believer in public debate and in allowing people to take extreme positions,” he tells me. “There’s a certain group of people that like to tell tall tales in public hearings. That stirs folks up. But in the end, facts matter.”

Fred Hill is betting heavily that its own set of facts will prevail.

Tim McNulty is a natural-history and environmental writer who lives in Sequim.