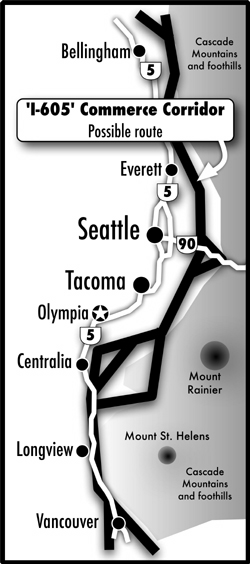

It’s a grand vision, as fresh and exciting as the 1952 New Jersey Turnpike. But our own special turnpike for the toolies would outdo New Jersey’s 148-mile pay-way by a substantial margin. “Commerce Corridor,” as the concept is sometimes called, would be a “north-south, limited-access corridor east of I-405 and west of the Cascades,” says the state Department of Transportation Web site. It would extend from British Columbia almost to Oregon, to “offer additional capacity for truck and passenger traffic as well as accommodate rail and utilities.” In other words, a freeway, minus the “free”—plus some wires, pipes, and a souped-up railroad. With a route extending from Sumas near the Canadian border to south of Chehalis, where it would merge with Interstate 5, the plan calls for creation of a 200-mile commerce conduit of roaring semis, giddy tourists, slurping pipelines, and rocket trains—just the thing to wake up, shake up, and suburbanize some of those way-too-sleepy and far-too-livable rural hamlets out there.

What the Legislature, the state Department of Transportation, and private promoters have in mind is a four- to 10-lane, privately developed, toll expressway, plus rail and utility lines devouring a right of way 350 to 450 feet wide through the heart of rural Western Washington, near and sometimes through the Cascade foothills.

It might be tempting to dismiss the notion of a new expressway out of hand as plainly absurd and hopelessly doomed. However, there are some very determined interests out there, not all of them knuckleheaded, who are more than willing to spend the bucks and do what it takes to move the project forward.

Paving paradise remains very big business in Washington, and freight is an important driver behind the corridor concept. In the 2003 legislative session, 42nd District state Rep. Doug Ericksen, R-Lynden, directed a bill through the House that ordered a study of the idea. Ericksen, a strong ally of construction and trucking interests, is the ranking minority member of the House Transportation Committee. Another strong proponent of the corridor has been Karen Schmidt, a former 23rd District Republican representative from Bainbridge Island, who, like Ericksen, is sympathetic to the Washington Trucking Association. Schmidt is now executive director of the Freight Mobility Strategic Investment Board (FMSIB).

Established by the Legislature in 1998, the FMSIB’s charge is to “promote strategic investments in a statewide freight mobility transportation system” through projects that “soften the impact of freight movement on local communities.” The board forwards its recommendations to the Legislature for funding.

Obviously, others are involved in backing the corridor idea, as well. State Sen. Jim Horn, R–Mercer Island, as chair of the Senate Highways and Transportation Committee, is among the more conspicuous advocates.

In previous iterations, the notion of a freeway east of Interstates 5 and 405 has variously been referred to as Interstate 605, the “outer beltway,” and “boondoggle.” After an initial study in 1968, a thousand angry residents attended a hearing in Bellevue to oppose it. The project was shelved, at least for a time. Similar proposals have come and gone. In 1998, with Seattle’s gridlock ever in the news, the Legislature funded a $500,000 study to stir up the ashes of I-605 and get the fire going again. The study was released in 2000, and while it was supposed to demonstrate that a new Eastside highway would substantially reduce traffic congestion on I-5 and I-405, the actual relief likely to be realized was found to be negligible and temporary, at best. Also, it would have cost $1.4 billion.

Following release of the study in 2000, the environmental group 1000 Friends of Washington said that I-605 “would completely devastate the Cascade foothills and would undo all of the region’s efforts to control California-style sprawl,” adding, “It should be stopped now.” Both Seattle and King County, as well as the Puget Sound Regional Council, have all taken stands against the beltway. The project’s likely contribution to sprawl well beyond the limits of established growth boundaries has remained among the top factors inspiring opposition.

In 2002, after much haggling over a slew of transportation troubles across the state, the Legislature placed Referendum 51 on the ballot, a $7.8 billion road construction behemoth that included funding for more studies of the outer highway and even some construction along parts of the route. R-51 was handily shot down by 62 percent of the voters that November. In reporting the defeat, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer included polling data that found that two-thirds of voters statewide wanted “a higher priority on transit and transportation choices.” More than three out of four voters preferred “a higher priority on safety and maintenance over new road projects.”

Nevertheless, within weeks, the beltway-that-wouldn’t-die was back.

With Horn at the helm of the Highways and Transportation Committee, the Legislature of 2003 offered new hope for shaking awake those sleepy little towns in the boonies. This time, not to be out- maneuvered by voters, the Legislature adopted a $4.2 billion funding package that did not require voter approval and raised the gas tax a nickel to fund a lengthy laundry list of road projects—plus more studies for more roads. Among them, the corridor concept. The state awarded a contract to study the idea to Wilbur Smith Associates, a large infrastructure consultancy. Its report is due at year’s end. (For more on the study, visit www.wsdot.wa.gov/freight/CommerceCorridorFeasStudy.htm.)

Risen from the dead once more, the Commerce Corridor appears to reincarnate practically the same scheme that voters turned down in R-51, this time extended all the way to Canada and most of the way to Oregon. The total price tag could exceed $100 billion.

By emphasizing the benefits to commerce and freight, and slight but temporary reductions in traffic volumes on I-5 and I-405, promoters surely hope to counter some of the worry over extensive and irreparable harm to communities and ecosystems across the affected 200-mile swath of Washington. Yet we have not heard much about the unavoidable impact, nor the mega-project’s inevitable role in promoting sprawl on a potentially disastrous scale. To assuage critics, Horn has suggested that interchanges could be spaced at 10-mile intervals, or more, as a check against sprawl. Critics don’t buy it and worry that scattered nodes of suburbia would be unstoppable, that the battle to stop future interchanges would be endless.

When the Department of Transportation polled residents in the I-405 corridor, 85 percent felt that bus service should be expanded and that steps should be taken to reduce the number of trips people make by car. To Horn and others, however, it’s almost entirely about infrastructure—there’s never enough. So we’ll have another study.

When completed, it might give a better sense as to whether the Commerce Corridor is dead-on-arrival goofy, or whether it truly means the end of life as we know it. Or both. We should learn more when the state holds the first public forum on the project on July 16 in Bellevue, from 9 a.m. to 12:30 p.m., at the state Department of Transportation office at 10833 Northup Way N.E.

Ken Wilcox is a Bellingham environmental writer and consultant.