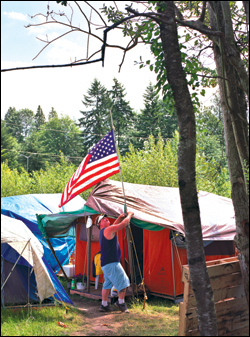

The Woodinville Alliance Church is debating whether to be the next host of suburban Tent City 4, which now calls Bothell home but still faces regulatory hurdles there. Tent City 3, meanwhile, is quietly relocating to St. Joseph’s Church on Seattle’s Capitol Hill. The area’s two roving camps for the homeless, typically moving every three months, consistently have managed to find new ground over the years, despite some angry residents, lawsuits, and nervous politicians. Determining what ground to call home next is an ongoing challenge, though—for the volunteers and residents, certainly, but also for the communities that are reminded of the homeless problem with every move.

Seattle is not alone in addressing homelessness with tent cities. Other places have similarly struggled with how to calm nearby residents and find a satisfactory level of regulation and infrastructure to accommodate homeless campers. Some tent cities have seen success, others have failed, and others have struggled, eventually, to be accepted. Four U.S. cities have faced the same issues challenging Seattle’s Tent Cities 3 and 4. They are:

Aurora, Ill.

Hesed House is a particularly good comparison to suburban Seattle’s Tent City 4 because the tent city there started almost 20 years ago as a ministry on church grounds and, like Tent City 4, is in close proximity to residential areas. During its humble beginnings, the camp moved each night to a different church, round-robin style. In 1985, the city of Aurora leased a piece of public land on the outskirts of the city to establish the shelter in a permanent location, according to Sister Rose Marie Lorentzen, executive director of Hesed House. Hesed House eventually came to be accepted by residents. “Over time, when their worst fears weren’t realized . . . , they realized there were people who were poor, but not necessarily bad neighbors,” Lorentzen says. “They have met their neighbors. . . . People fear most what they don’t know.”

Lorentzen says the support and cooperation of various churches were key, as was the eventual cooperation of elected officials, who, at first, were “a little bit uneasy. But so many of their constituents are volunteering at the shelter, it changes things.”

Los Angeles

In 1993, homeless activist Ted Hayes founded Dome Village with the help of a $250,000 grant. Located in downtown L.A., Dome Village consists of 20 dome structures, some for living, some for cooking, even one for teaching residents computer skills. Like Seattle’s tent cities, families are allowed to stay together, which often is not the case at traditional shelters. “Most facilities are segregated, so when [residents] graduate to society and there are kids and dogs and blacks and everything else . . . , they fail,” says Hayes.

Los Angeles has strict building codes and very partisan politics, Hayes says, and people told him he’d never see a program like Dome Village work in his lifetime. “We’ve had to earn it every step of the way,” he says. “We made everybody mad at us. It was just being persistent and consistent” that led to success.

Portland

Dignity Village was founded in 2000, and initially Portland’s tent city had problems similar to Seattle’s, according to Jack Tafari, a frequent spokesperson for the village. The tent city was given 60 days to find a new site after a community meeting at which angry residents called for relocation. Finally, the city offered to lease a site on the outskirts of Portland, between a prison and a warehouse, and the lease has been extended several times.

Marshall Runkel, assistant to Portland City Council member Erik Sten, says the location on unused land outside the city, with few immediate neighbors, has helped Dignity Village succeed. “It’s rational to have concerns about an experimental homeless camp,” he says. In the two years since Dignity Village moved in, crime in the area has been consistently lower. “Our impact on the neighborhood is not only negligible” in any negative sense, “it’s been good,” says Tafari.

There is a fence around the village and a guarded entrance. Like Seattle’s tent cities, violence, drugs, and alcohol are not tolerated, and the village is not government funded. Dignity Village is its own nonprofit organization, while Seattle’s tent cities are under an umbrella organization, SHARE/WHEEL.

Denver

When Dallas Malerbi, a graduate student at the University of Colorado, heard that the mayor of Denver was creating a commission to end homelessness, he and other advocates for the homeless began drawing up a plan for an officially sanctioned tent city. They researched the needs of Denver’s homeless population, addressed concerns of politicians and citizens, and cited examples in other cities. The result was a 39-page report.

“The bottom line is that we want a safe, legal place for people to be outside,” says Malerbi. However, on May 10 the Denver Commission to End Homelessness voted overwhelmingly against the proposal. “One of the concerns was the safety of women and children,” says Deborah Ortega, executive director of the commission. “The other issue was that Colorado has such frigid temperatures compared to other cities.” The commission is looking at long-term solutions as well as more funding from the state for housing vouchers and increasing capacity at a conventional shelter. Ortega concedes that the city does not have enough shelter for the more than 9,000 homeless people in Denver, although an interfaith group has been trying to fill the need.

Ortega holds out little hope of a tent city succeeding in Denver. “The city charter has to change, city ordinances would have to change, and the political will has to be there,” she says. “I think it would be very hard if they tried it again.”

the tent cities that have succeeded all initially had problems with location. In Illinois, Hesed House moved every night. Dome Village in Los Angeles is the second tent city organized by Hayes—after the first was bulldozed by the city. Even Dignity Village in Portland, which has become something of a national model, moved around until it found its current site. In Portland and Illinois, politicians willing to work with activists have been key.

Community involvement and working to make the area around a tent city safe and clean has proven to be important in assuring concerned residents. Dignity Village leads tours of schoolchildren and community groups through the camp to raise awareness. That’s happening in Seattle, too. In Illinois, Hesed House enlists the help of Aurora residents who volunteer time. They get to know residents and their stories. Strict rules are enforced in all of the successful tent cities. Toronto had a tent city, but it was bulldozed because of rampant drug use. Drug use or overcrowding has led to the breakup of tent cities from Vancouver, B.C., to Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

There is wide agreement among advocates that tent cities are not the real solution—only a short-term one for a serious problem that needs a permanent answer. “These are substandard living conditions,” says Hayes, “and we cannot let this become the standard.” Says Runkel of Portland’s seemingly successful example: “This is a new low. Nobody should mistake this for a victory.”