For Mike Skinner, “keeping it real” means spending 30 seconds rhyming about getting money from a cash point. Skinner’s first album as the Streets, 2002’s Original Pirate Material, was filled with a love for everyday British life that clicked with me immediately. A Londoner, I’d seen scuffles in kebab shops, been on brandy-fired nights out, and sat in greasy cafes the morning after. Here it all was on CD—and Skinner’s awkward rapping just enhanced the everyman appeal. The excellent follow-up, A Grand Don’t Come for Free (Vice), patches Skinner’s running commentaries, internal monologues, bar-stool tales, and overheard chitchat into a single story.

To balance this contrivance, Skinner’s performance this time is even more naturalistic. On “Such a Twat,” the song stops suddenly as the hero’s cell phone cuts out—”Aw, fucking phones, man!”—and then apologetically carries on. “I think we got cut off/Yeah, I got crap reception in my house/I have to stand in a certain spot in my kitchen or it cuts out.” Other songs are dotted with pauses, “um”s and “yeah”s, and interruptions from friends. These are cute, but they also make the album a lot more intimate. Breaking the flow of songs with this lyrical chaff makes you forget you’re listening to “songs,” not conversations. When I first saw A Grand Don’t Come for Free‘s lyrics written down, I was shocked to see that they actually rhyme.

A Grand Don’t Come for Free is something like a fly-on-the-wall documentary: 11 scenes in 50 minutes, edited from the sprawl of Skinner’s life. Skinner is the director as well as star and scorer, adjusting music and flow to suit the action. If that means he needs to sound stupid, he will: “I could not remember what I wanted to order/Which lost me my place in the queue I’d waited for—yeah!” he raps on “Fit but You Know It.” That rhyme sounds as clumsy as it reads, but his staccato delivery over a dumb guitar loop exactly fits the song’s mood of drunken lads on holiday. Come to the Streets expecting traditional hip-hop mike skills and you might draw back in horror if not pity. Mike Skinner was a hip-hop MC in his teens, though, and he understands plenty of the music’s essence: Get the listener involved, use a language they believe in, pile on the detail, and tell the kind of stories that fit your style.

The backing tracks on A Grand are like market-stall fakes of precisely current trends. “Get Out of My House” sets a domestic argument to London’s “grime” sound, an underground music that emerged from hip-hop and house, based on staggering rhythms and PlayStation blurts (see Jess Harvell’s sidebar). “Such a Twat,” with its acid-house squeals and gothic keyboards, is an urchin take on crunk. On more narrative tracks, Skinner likes to use curls of synthetic strings, giving details about borrowed coats or returned DVDs a mock-Hollywood grandeur. The beats can sound rudimentary, but they fit the story elegantly—for the finale, “Empty Cans,” Skinner uses the same rhythm on two alternate endings and lets instrumental color (queasy low bass or soothing keyboards) switch the mood.

A Grand wears its narrative lightly. A man loses some money, meets a girl, and then finds his world falling apart. Mike Skinner doesn’t try to cram too much in, but by telling a story at all, he risks including makeweight tracks that exist only to move the plot along. He partly gets round this by avoiding any kind of bridging—each song homes in on one or two events, leaving you to fill in the gaps yourself. Even so, some tracks are plot heavier than others. “What Is He Thinking?” is the story’s lynchpin—Mike sitting in a room, staring at his friend, waiting for a confession while the rhythm jumps like a guilty heart. “I can’t just deny it ’cause my face shows/Lookin’ at the telly’s not aiding, no.” It’s story specific, but Skinner’s discomfort and suspicion are familiar and give the song urgency and life beyond its moving the action along.

The depth and joy of A Grand Don’t Come for Free lie in how Skinner makes his story universal by building it out of familiar situations. Listening to “Could Well Be In” the first time, you don’t think about where it fits the album’s narrative—you just recognize the nervous wonder of a first date. Mike makes clumsy guesses at a girl’s intentions over a disarmingly tender keyboard figure, and by the end of it I was cheering him on. That sets us up for the gut-knotting comedown of “Dry Your Eyes,” which sketches the narrator’s failed scramble to save the same relationship. These two songs are the record’s loveliest and show off Skinner’s rare eye for detail: Instead of just having Mike wallowing in bliss or agony, he tracks the beginning and end of a relationship by calmly observing a couple’s body language—from “She had her fingers round her hair, playin’/I saw on TV that’s a good indication” (“Could Well Be In”) to “She peels away my fingers, looks at me and then gestures/By pushin’ my hand away to my chest, from hers” (“Dry Your Eyes”). The more specific he gets, the more universal he becomes.

Every track on the album becomes richer by being part of a story—the troubles Mike goes through in the second half of A Grand cut deeper after a glimpse at his happiness in the first. Skinner’s workaday details escape banality by being part of a life we’ve come to know, and their realism helps him avoid melodrama. Until “Empty Cans,” that is, with its ludicrous, glorious twist ending. The first time through, I felt thoroughly manipulated, but by that time I liked Mike Skinner too much to care. I also cried—the first time music’s done that to me in five years, and the first time ever sober. What caused it? A description of a man helping his friend repair a television set.

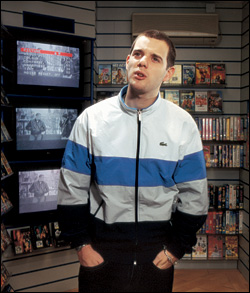

The Streets plays Neumo’s at 8 p.m. Tues., June 15. $15 adv.