Of all the indie-spawned new-rock- revival bands, the ones that stand out have a name that completes their persona. The Strokes denote sensual motion; the White Stripes, dynamic design; the Rapture careen woozily like a suddenly unoccupied car. The Stills, however, are much harder to grasp. Do they remain quiet and motionless? Are their static portraits culled from moving pictures? Is their presence essential to the processing of alcoholic beverages? If band names advertise a certain aesthetic, then the Stills may unwittingly highlight the core of their music: vagueness.

It’s not just the meaning of their moniker that seems hazy and unknowable. Chances are you’re wondering who the Stills are, which is OK, because I am, too. What I know so far: They’re originally from Montreal, though before recording their debut album, they spent some time performing in N.Y.C. There are four members: two guitarists, a bassist, a drummer. Two of them—vocalist/guitarist Tim Fletcher and drummer Dave Hamelin—bought a four-track machine a couple of years back from a friend who needed cash in a hurry. (That’s a win-win situation: One was able to pay his dope dealer or his student-loan officer, while the other two were able to realize their dreams.) But this transaction seems like the only detail that gives the band a three- dimensional history, and what happened afterward is left to the imagination. “A like-minded songwriting aesthetic ensued,” quoth the band’s Web site, though it is unclear whether they mean like-minded between Fletcher and Hamelin or between the Stills and every indie band in New York.

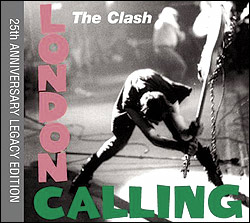

Odds are you’ve seen Interpol mentioned in conjunction with the Stills, which is understandable. Both groups share the subway-tunnel echo, the sharp-suited nonchalant urgency, the chk-chk-boom percussion of a host of ’80s bands whose names have been dropped so often they’re practically on bungee cords. The Stills are missing something: Interpol’s coy precision, the liquid contortions of the post-post-punk groups of N.Y.C.’s DFA label, the feeling that they’re more than just figments of some world-weary Williamsburg scenester’s insufficiently active imagination. Yet they neatly fill the auditory gap in the New York music scene where that smack-shake-rattle groove is supposed to be, evoking more than a tang of the dour, foggy-Sunday-afternoon laments of post-Oasis Britpop.

Somewhere in all the echoes of Bunnymen and Factory-direct rhythms on the Stills’ debut album, Logic Will Break Your Heart (Atlantic), the band acknowledges the Manchester heyday of U.K. post-punk, siphons it through a Coldplay filter, and sweeps the pills, thrills, bellyaches, and belt hangings under the rug. The resulting sound is interesting as revisionist history, if not so much as music. “Ready for It” is the most telling display of this technique: At the halfway point, choppy skinny-tie riffs spar with frontman Tim Fletcher’s undulating melodies as the song’s up-tempo churn knocks out an inspired moment of Devoto-esque guitar lunacy. Then the whole thing collapses into a sleepy, go-nowhere pseudo-waltz that ambles like a mid-fi trash-bin refugee from OK Computer. “Love and Death” has just enough minor-key gloom to pass for a Cure knockoff, though the guitar seems to owe more than a little debt to Albert Hammond Jr. Which isn’t the last of the Strokes parallels: Fletcher’s voice resembles Julian Casablancas warbling through Thom Yorke’s throat—a buzz that mostly resonates as a mumbling series of drawn-out syllables swaddled in overly grandiose melisma.

Every so often, Fletcher remembers that he’s singing words instead of sounds, and he manages to enunciate coherently just often enough to be slightly quotable. Much has been made of the Stills’ attempts to address post–9/11 America, though the majority of their diatribes seem intangible and oblique. Elliptical references to a “comfortable flight” aside, the only thing telling about “Let’s Roll” is the title, and the abstractionist “Lola Stars and Stripes” murkily posits U.S. foreign policy as a fragile romance: “With an M-16 you’ll feel the surge of your American past/But are you afraid/You always said the world would never last.” The band writes gothic permutations of love songs and war lamentations, but one line from “Animals + Insects” only demonstrates the pretend-shock sociopathy of a faux Morrissey: “I throw grenades at a Christmas choir.” Suffer little children, indeed.

Throughout the album, a downward-staring lethargy rides over plodding variations of the same 4/4 beat: Songs like “Changes Are No Good” make for an interesting chorus but a boring mise-en-scène. While the individual songs seethe with jet-engine guitar and deeply reverbed drums, they’ve congealed with one another by the last track. By the end, the Stills sound almost completely static. And if they want to make their name, they’ve got to stop living up to it.

The Stills play Neumo’s at 8 p.m. with Sea Ray. Thurs., June 13. $13.50 adv./$15.