“If you look at the ground right here, you can see it’s fairly easy to see footprints,” Joel Hardin tells me. The 64-year-old Hardin, a former Border Patrol agent based in the suburbs of Bellingham, is an internationally renowned “tracker,” a kind of detective, able to find missing persons, catch fugitives, and identify terrorists all from the subtlest of signs and imprints on the earth. I look at the area he directs me to, a gravel path dotted with inch-high vegetation leading to a wooded patch near Marysville, and see nothing.

Hardin, wearing a flak jacket and jeans, bends down, enjoying the process of teaching people to see what they didn’t see before. “See this little bit of grass that’s been damaged?” He points to a blade of grass, maybe a quarter-inch high, that has a slight kink at the end. That’s the mark of a foot, he tells me, as is the way other blades of grass lean forward rather than stand straight up. What’s more, he says he can tell that the shoe has a heavy lug, like his own hiking boots. Right next to the bent grass are some blades that are standing straight up, apparently untouched because they could fit into the high wells between lugs of such a shoe.

On my hands and knees, I can just make out the kinks and the bends in the grass. But someone like Hardin can take it all in at a glance, seeing a whole trail of footsteps down the length of the path. That skill puts him in growing demand. Hardin, as proprietor of Joel Hardin Professional Tracking Services, teaches classes to various law enforcement, military, and search- and-rescue groups around the country. Hardin is currently working with the Marines to develop a tracking curriculum for their special-operations forces. Since 1987, he’s been teaching the U.S. Army’s special-operations instructors.

But you don’t have to be a warrior, or a cop, to track. Hardin and others teach some classes that are open to the public, upon whom search-and-rescue organizations depend. Another branch of tracking looks at animal footprints and signs as a means not primarily of pursuit but of communing with nature. A national leader in this kind of tracking can also be found locally in the Wilderness Awareness School, located in Duvall. Luckily for Seattle enthusiasts, the school has just moved the meeting spot for its tracking club from Sultan to nearby North Bend.

Back in Marysville, I ask Hardin about his claim that tracking will allow you not just to follow footprints but to understand the mind-set of the person who made them, what that individual’s “purpose and objectives” were, whether that person was “nervous or panicked or confident.” He and his companion Bob Brady, an erstwhile tracking student of Hardin and a volunteer with both the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office and the county’s Search and Rescue team, demonstrate. First, Brady walks like someone who’s confident, someone who knows where he’s going. He strides down the path, one foot following another in a fairly straight line. Next, Hardin follows as if he’s nervous or doesn’t know where he’s going. He walks a few feet, then turns around to check for landmarks. Finally, Hardin meanders down the path as if he’s come out here just to think and be by himself. His feet turn outward as he walks from side to side, gazing at the surrounding plants. It’s easy to see, now, how each mode of walking leaves a recognizable pattern of footprints.

As we gather by a tree to talk more, Hardin tells me that you can even see by our footprints who is the “boss” of this meeting—me. Since they’ve been addressing me all along, the prints of Hardin and Brady are always turned toward mine.

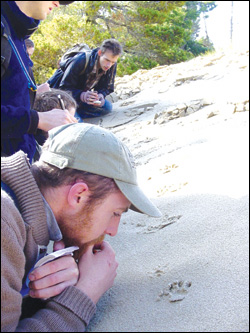

Tracking animals provides a different sort of mystery, with a central question being, what kind of animal made those footprints? One gloriously sunny Sunday morning, I travel with the Wilderness Awareness School’s tracking club to a fork of the Snoqualmie River shaded by towering cottonwoods and banked by sand and muddy soil perfect for tracking. At 7 a.m., staffers and interns with the school came out here and identified six different sets of tracks in various locations that will serve as “stations” for our examination. Each of the six groups will spend time at every station with an expert “stationmaster” who will provide clues while trying not to give too much away.

At one station along the river, we see deep imprints of what we guess to be claws. “If you’re seeing claws, they’re most likely not retractable,” stationmaster Greg tells us. “Animals that use claws for hunting don’t want to waste them on walking.” This animal was a dog, Greg reveals, wanting us to focus our attention on another question: When were these tracks made? He points out what look like pin prints in the surrounding sand but are really the markings of rain. Can we see evidence of rain in the tracks themselves? We can’t. That tells us the prints have been made since the last rain, the night before last. “The next thing to check is whether there are any spider webs in the tracks,” Greg says. Spiders love tracks, and if there are any webs, the imprints couldn’t be that fresh.

Before we have time to age the tracks more precisely, it’s time to move downriver to our next station, where we can see the clear imprint of toes as long and slender as fingers. “What kind of animals have feet like this?” stationmaster Evan asks. We’re stumped. “I’ll give you a hint,” Evan says. He shows us how there are actually two sizes of prints, indicating that the animal’s back feet are bigger than its front. “It’s pretty chunky in the backside,” Evan says. He also shows us tiny lines connecting the toes, telltale signs of webfeet. So it’s a chunky, water-dwelling animal. An otter? A beaver? It is a beaver, Evan tells us, the largest rodent in North America.

Though we quickly learn a lot from these mysteries, the biggest thrill of the day comes without a mystery to solve. We see huge, deep prints obviously from some hulking animal—elk prints, someone lets slip. Newly attuned to the impressions different animals make on the land, I’m in awe of their scale. Stationmaster Dan can tell the elk was probably around 6 and a half feet tall and weighed between 300 and 400 pounds. We follow the prints through some spindly trees, and find a tan tuft from the elk’s hair hanging on a branch. Dan shows us how the hair kinks if you bend it, a distinguishing characteristic of the hair, which is hollow.

At the end of the outing, we sit in a circle on the ground and discuss what we found. Gabe Spence, head of the Wilderness Awareness School’s tracking program, has one more revelation up his sleeve. It turns out that students from the school, which runs an array of programs including one that teaches survival skills, have come out this morning and hidden in the environs as a kind of test. “I can guarantee you that everyone came within eight inches of somebody,” Spence says. Nobody noticed, our awareness skills yet to be perfected.

The Wilderness Awareness School’s tracking club meets one more time, on June 6, before taking a break until September. But during the summer, the school is offering a series of daylong tracker-trainer classes in the field, as well as a weeklong wolf-tracking expedition to Idaho in August. (Register by July 8 for the Idaho trip.) To find out more, see www.wildernessawareness.org or call 425-788-1301. To find out about Joel Hardin’s periodic classes open to the public, call him at 360-966-7707 or see www.jhardin-inc.com.If you’re interested in joining the King County Search and Rescue Association, which maintains a tracking unit, see www.kcsara.org or www.pacificnwtrackers.com. Those in Snohomish County can contact Bob Brady at tracku2@gte.net or see his Web site: home1.gte.net/tracku2/trackingpage2.htm.