Cee-Lo is a young man with an old man’s voice—a 28-year-old who sounds like an old Southern Baptist preacher. When I first heard his raspy, pulpit-rooted tenor on a Goodie Mob album, I thought that either someone had come up with a great gimmick—the gospel rapper in a secular world, the humanist among nihilists—or that someone’s dad had wandered into the studio and commandeered the mike. But while Cee-Lo’s preacher-rapper style isn’t a gimmick, it is an act. Preaching, after all, is a performance, and it’s something Cee-Lo comes to honestly. Both of his late parents were ministers, and they seem to be spiritual guests on their son’s records just as much as Satan was the third wheel at the Cheney-Scalia duck-hunting powwow.

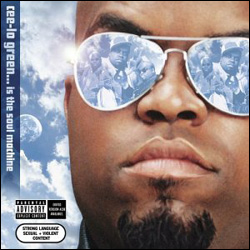

Among the living, OutKast provide Cee-Lo’s obvious benchmark. When the history of genre-jumping ’00s hip-hop solidifies, Cee-Lo’s 2002 release Cee-Lo Green and His Perfect Imperfections might be called Pet Sounds to The Love Below‘s Sgt. Pepper: the sadder album that arrived first but earned less money and initial acclaim. Perfect was meandering, low-key, and deep in that we’re-stoned-and-everything-seems-deep sort of way. Like any good jam album, it offered cool vamps and headphone epiphanies, but few of the hooks that define Cee-Lo Green Is the Soul Machine. The former album was self-produced, strange, and destined for cult status. The latter, a superstar-producer round-robin featuring Timbaland, the Neptunes, Organized Noise, Jazze Pha, and DJ Premier, wants the airwaves, and it wants them now.

To continue with comparisons to albums recorded by chubby hippies, Soul Machine might be Cee-Lo’s Workingman’s Dead—proof that his inherent freakiness doesn’t mean he can’t do pop songs. The album is loaded—larded, even—with hooks imported from near and far: the Jonzun Crew, the gospel classic “Jesus Is on the Mainline,” Steely Dan, the Staple Singers, Oasis, “Pass the Kutchie,” Al Green, even “The Carol of the Bells.” That last reference comes on “Child’s Play,” which spurs Cee-Lo and Ludacris to heights of staccato versifying.

But these days Cee-Lo is a singer as much as a rapper, and among current black pop’s fearlessly limited vocalists, he’s less of a goof than either André or Pharrell. His croon has gotten subtler, more sensuous. On all fronts, he’s easy to love. Though his attempted commercial breakthrough is partly a retreat from his more cohesive and idiosyncratic debut, it’s no sellout, and it just happens to be better.