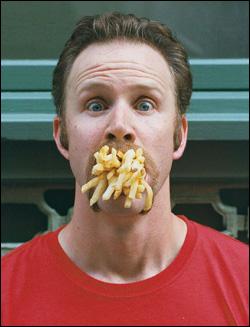

You do not want to eat anything before seeing this movie. And certainly not after. Avoid the snack bar. Empty your pockets of clandestine candy. Fast all day prior to seeing it, if necessary. Then go—this is an important film. Morgan Spurlock’s Super Size Me (which opens Friday, May 7, at the Seven Gables and Uptown) is a must-see documentary, despite its flaws. It’s disgusting, and that isn’t a flaw at all. Disgust is, after all, a communiqué from the stomach to the brain, and this gastric report is long overdue. The writer-director-subject, who sentences himself to a monthlong all-McDonald’s diet, also sentences us to the sight of him vomiting, bellyaching, groaning with nausea, and submitting to a rectal exam by one of his understandably concerned doctors. At the beginning of the Jackass-meets-Nader stunt, he’s a healthy Manhattan hipster. By the end, he’s a Golden Arches addict, a junkie with no pride or dignity left to him. His vegan chef girlfriend confesses to the camera that his lab-rat menu has almost made him impotent. Meanwhile, Spurlock gains 25 pounds during his exercise-free, vegetable-free experiment. He’s got Ronald McDonald on his back, and he can’t shake that foul clown.

Spurlock’s premise is the 2002 suit of two obese New York teens against the McDonald’s corporation that allegedly made them fat. It’s ridiculous, he acknowledges, to deny the role free will plays in the supersizing vs. healthy-eating equation in America today. But he seizes upon this inanity—the saturated fats and sodium made me do it!—with all his teeth, as it were. The teens’ case is doomed for lack of scientific evidence to support it, so Spurlock decides to make himself an entirely unscientific experiment, an affable guinea pig, to the horror of girlfriend, parents, friends, and physicians.

This is the George Plimpton–esque aspect of the film, the director’s willingness to subject himself to total humiliation in the course of participatory journalism. It’s Eric Schlosser (Fast Food Nation) meets Michael Moore.

WHAT’S MISSING, however, is a more genuine connection with the interview subjects Spurlock surveys during the road-trip portion of his documentary. He conducts man-on-the-street interviews with morons who can’t even define what a “calorie” means. The effect is somewhat patronizing to those flyover types—from Iowa to Arkansas, from the Ozarks to the Kitsap Peninsula—for whom the cheap, quick, satiating Mickey D diet is often consumed out of necessity.

No matter how well-intentioned (where opportunism and concern tip at the fulcrum’s point), Spurlock himself is simply less compelling, less interesting, than those he meets on his odyssey—like Subway weight-loss spokesperson Jared Fogel. Spurlock also encounters a 16-year-old teen and her plus-size mom in Texas for whom obesity—and unhealthy crash dieting—aren’t simple issues of choice. Then we watch gruesome portions of a surgery in which a despondent guy has his stomach stapled. These people aren’t making movies for Sundance (where Super was a great hit); they’re fighting for their lives. Spurlock ridicules his own ballooning from 11 percent to 18 percent body fat under a medically supervised experiment (“My body officially hates me!”). But what about those poor souls who start at 20 percent or higher, who lack health insurance at their minimum-wage jobs at McDonald’s and Wal-Mart, who can’t go back to their support groups of dieticians, vegan chef girlfriends, and SoHo M.D.s? Here, Spurlock stoops to commiserate.

I’m not suggesting he lacks empathy for these people, but we know his greasy immersion will eventually end. I had more of a problem with Michael Moore’s early career, when he was mean to the rabbit lady and the fey hotel clerk in Roger & Me, a watershed documentary about corporate responsibility to which Super is heir. Today, though Moore relies too much on his regular-guy persona, part of what makes his compassion more convincing is that he’s fat—he truly is an average American in that regard. Moore would’ve made a better film on the subject. But Spurlock’s just starting out in his career, and I’m glad more muckraking filmmakers are now following the path Moore first waddled.

With a background in the Internet and TV, Spurlock clutters the frame with a battery of depressing statistics and cheap graphics. They do get a little annoying—like footnotes you’d rather read later. He also undercuts the voice of NYU’s Dr. Marion Nestle (Food Politics) and other real authorities by giving equal screen time to some marginal figures. Super is not a very well organized film; its structure and drama are mainly provided by the calendar countdown of Spurlock’s anti-diet. As day 30 nears, his girlfriend and mother grow tearfully concerned for his health. One of his doctors warns, “Your liver is now like paté.” But if he quits, he’ll never reach Sundance.

The challenge is now to see if Super will reach beyond the Sundance elite, beyond the thin, urban markets of coastal sophisticates who’ll laugh and groan at Spurlock’s antics, agree with his points, then go out for tofu phad Thai after the show. Most of those who see the movie—or are reading this review, for that matter—won’t really need to. It’s the less affluent, less educated Americans—the 16-year-old Texas girl, the stomach- stapling guy—who really need to watch. And the problem is that, like the similarly important Fast Food Nation, there’s a certain top-down, preachy liberal dynamic at work here.

America hates scolds and loves indulgence. That’s why it savors SUVs and supersizing and why it voted for Bush, against whom Spurlock gets in a few digs. But he reserves his greatest outrage, as he should, for the way McDonald’s and other food-industry forces target children (the fastest-growing segment of fatties, trapped in suburbs where no one walks or rides a bike to school). Here, too, the problem is how to reach these kids. If Dubya, or Americans in general, really cared about their children, Super Size Me would be playing in every school across the nation—on video monitors sitting right next to the Coke and candy machines in the hallways.