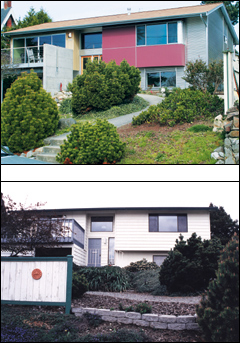

It’s a house only a mother could love. That mother is Laura Logan, who spotted the unremarkable Kirkland structure in 2002, not long after a divorce. She already had an 8-year-old daughter, but here was a foundling that really, really needed some loving care: a modest 1980 split-level home of about 2,000 square feet, sitting on a prime, west-facing lot with views of Lake Washington and the Olympics. Despite its $550,000 price tag, it had “no redeeming features,” Logan recalls thinking. “These houses are just rectangles.”

So, in your ordinary Eastside scenario, you’d expect her to call the bulldozers, then replace it with a brand-new palace that dwarfed her neighbors, maybe even with a helicopter pad out back. Bigger, newer, more expensive, right? Not this time. Even on the Eastside, a new respect for old bones is emerging. As Seattleites slaving over their 1920s Wallingford bungalows well know: Bigger isn’t better, and sometimes you have to work with the history you’re given— even if there’s only 24 years of it.

Most of the Eastside’s older housing stock dates to the building of the bridges: ranch houses and ramblers from the ’50s and ’60s, many of them located in the closer-in neighborhoods with shorter commute times to Seattle. A lot of those properties are now coming onto the market as empty nesters and widows sell the old suburban homestead (especially given property taxes). They’re not architectural gems, but neither are they automatic tear-downs.

But even lower in the suburban pecking order than the ranch house, mocked in a current Century 21 ad campaign, comes the split-level: the even uglier step- stepsister to the ugly stepsister of the cul-de-sacs. Building “on spec” (speculation), developers simply purchased off-the- rack blueprints and threw a house on a lot in order to sell the land. As Logan’s contractor, Jed Johnson, explains of the split-level: “It dominated the spec housing market of the ’70s. It got to be stereotyped [as] not that desirable.” Yet of Logan’s home (built in 1980 but very much a ’70s design), he adds, “The house had held together fairly well—it was just dated.” Better still, because of the split-levels’ inexpensive, ubiquitous simplicity (with no interior bearing walls), they’re relatively easy and affordable to reconfigure. “They open up a lot of design possibilities.”

DETERMINED TO involve herself in every stage of the remodel, Logan did most of the opening up herself, including demolition work. “Basically I took the house down to the studs,” she remembers. “I had strong ideas about what I wanted to do. It’s the little project that grew.” She also kept costs down by serving as Johnson’s contractor’s helper on the project. “I want to be your lackey,” she told him.

Logan subsequently called in architect Brett Burnette. “It is a simple house, and you don’t want it to get too complicated,” he says. “It was a matter of tweaking it here and there.” While Logan, fond of modern and industrial materials, initially wanted to clad the house in corrugated metal, Burnette instead promoted the eventual scheme of mixing that metal with other materials (wood siding, concrete, and red-painted concrete-board paneling) on the front facade and also knocking off a small corner of the same frontage so the home didn’t “read as a simple box.” They also decided to expand the master bedroom into the backyard, pouring a foundation down to the basement level (to be Logan’s future metalsmithing studio). This was the most expensive component of the estimated $180,000 remodel, which added some 250 square feet to the two-person household.

“I’m into renewable resources. I wanted to use as little wood as possible,” says Logan. Outside, the decks were redone with fiberglass strips and metal-and-cable railings. Inside, new flooring in the open kitchen/dining/living/ piano area is carbonized bamboo (an environmentally friendly resource), while the countertops and sink are made of black-colored epoxy resin, a durable material generally used in laboratories.

Above the resulting great room-style space, Burnette had the idea of revealing the overhead trusses, creating a vaulted ceiling in place of the old, low popcorn-finish ceiling. Then Logan found some overstocked fir flooring at Dunn Lumber and had Johnson install it—where else?—on the now-heightened ceiling.

With piano, kitchen, and flop-down furniture facing the commanding front windows (doubled in size), Logan observes, “It’s the way we live. I like the look of a modern house;” i.e., without rigidly compartmentalized living, dining, and cooking spaces—all of them separate and small, as split-levels were originally laid out.

THAT IMPROVISATORY spirit speaks to Kirkland’s increasingly mix-and-match urban fabric. Logan’s house sits on a formerly subdivided orchard, with surviving fruit trees in front and back; next door is the original 1890s farmhouse. Around the corner are trophy homes and cheapo ’40s saltboxes in equal number; down the hill toward Central Way are condos, condos, condos. An Eastsider since 1989, Logan says, “Kirkland is, to me, the only neighborhood on the Eastside that’s like a Seattle neighborhood. The others are too suburban.” (See related story, p. 35.)

Does that mean Kirkland is now leading the vanguard of Eastside urbanization? It’s certainly denser and perhaps more diverse in terms of family structure. Logan points to neighbors who are retirees, single parents, and “standard nuclear families [with] kids playing around from yard to yard. This neighborhood is really mixed.” Yet, she concedes, “There are more tear-downs than remodels.” While an exception to that trend, her spiffed-up split-level says at least one thing about the future of Eastside development for all manner of households: “They don’t have to be the big mega-mansions.”