IN THE BEGINNING of Vessels of Vibe (which continues this weekend at the Broadway Performance Hall, 206-371-8287), Lelavision co-directors Ela Lamblin and Leah Mann sit high above the stage floor on a pair of trapezes, looking down on a landscape full of Lamblin’s signature musical instruments. Over the course of the evening, the pair will “play” each one of them, and the program will finish when they play the last one. As a structural device, this is not high drama, yet each whimsical adventure manages to keep us focused and entertained.

In this new work, Lamblin and Mann establish a relationship reminiscent of music-hall entertainment: He’s a bit goony and lanky, she’s smaller and buzzing around like a mosquito. When they each, like a pair of orchestra conductors, wave their way through different time signatures—he grandly tracing the four sides of a square while she slashes along the three sides of a triangle—they’re stunned to discover that four times three equals three times four and they’ve ended up at the same spot. When he gives her a long look, she answers with a brisk nod, her hair piled up in a Pebbles Flintstone do, playing the Gracie Allen role, adding the rhythmic period to the end of his longer phrases.

Several of Lamblin’s musical sculptures are making a return appearance here, such as the “Rumitone,” which is named after the 13th-century Persian mystic but resembles a kind of spinning nose cone with violin strings, and the “Longwave,” a set of harp strings stretched across the width of the stage. In one black-lighted section, the performers’ white-gloved hands seem to play the “Eensy, Weensy Spider” as they climb up the strings, then are transformed into a white-on-black version of an old Disney Silly Symphony, where the obsessive synchrony of music and movement has a slightly macabre feeling.

Lamblin has added several new pieces. His amalgamation of a playground turntable and a set of metal pipes spins like a prayer wheel, with Lamblin and Mann curled up in the center. As they shift their weight toward the edges of the base, they slow down, and the rumble of the ball bearings seems lower pitched; when they pull back together, the pitch rises as their bodies do. These simple demonstrations of music physics have a hypnotic quality.

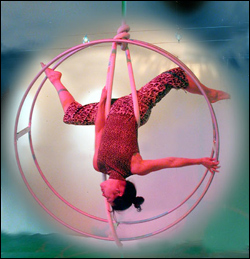

Lamblin’s most recent creation takes momentum on a much wilder ride. Suspended above the stage, an aluminum double hoop hung with bells acts as a trapeze and a gyroscope, spinning in two planes simultaneously. With Lamblin riding in the center, stretched out like da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, he makes music through his dancing in a kind of chaotic balancing act.

Lamblin and Mann call their work “physical music,” and the evening’s most powerful moments are when they are totally involved in making music from a pair of metal bowls or a Styrofoam cooler. When they put down the instruments, they lose that sense of intention as their movement becomes “just” dance. The work doesn’t have the gimmicky feel of Stomp or Blue Man Group, but as section follows section, most of them resolving in a slow deceleration and a blackout, we could use some kind of connecting thread to make sense of the collection of sounds and images.