A former New Yorker, keyboardist Wayne Horvitz had already made a name for himself in that city’s downtown jazz and improv scene when, in the mid-’90s, he relocated to Seattle. Here, he began working with a wide-ranging mixture of local musicians, most notably in the groove unit Zony Mash, which recently disbanded after a decade together, as well as Ponga (featuring drummer Bobby Previte, saxophonist Skerik, and keyboardist Dave Palmer) and the Four Plus One Ensemble, alongside violinist Eyvind Kang, trombonist Julian Priester, keyboardist Reggie Watts (also of Maktub), and on electronics and processing, Tucker Martine. Martine’s résumé is as varied as Horvitz’s; he’s produced or engineered for artists as varied as electro-beatscapists Land of the Loops, jazz cats Kang and guitarist Bill Frisell, and indie rockers Sick Bees.

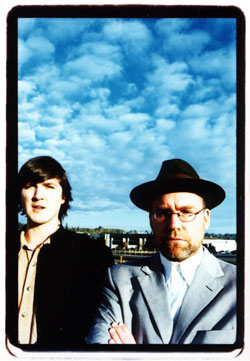

Mylab (Terminus), the self-titled debut of Horvitz and Martine’s new collaborative project, is something of a Seattle all-stars project, utilizing the talents of Frisell, Kang, Previte, Skerik, vocalist Robin Holcomb (to whom Horvitz is married), and Watts, among others in the same orbit. The disc is all over the place stylistically, taking in everything from Afro percussion to laptop glitch to blues guitar, but the disc’s late-night mood and ingratiating, offbeat grooves line it up alongside stoner-friendly fare like DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing . . . as well as jazz-informed hybrids like Marc Ribot’s Los Cubanos Postizos; it’s both a logical extension of Horvitz and Martine’s previous work and an intriguing sidestep. The Jukebox took place at the Weekly offices on a mid-January afternoon.

Radiohead: “Everything in Its Right Place” (2000) from Kid A (Capitol)

Tucker Martine: Radiohead, Kid A. Definitely one of my favorite records of the last five years.

Seattle Weekly: There’s a little bit of that album’s feel on Mylab. I’m wondering if that’s intentional.

Martine: On the 10th track [“Not in My House”], actually, I was kind of aware of the possible similarities.

Horvitz: I didn’t think we had an intent [other than] to do something together. We certainly never had a conversation where we listened to other people’s music or said, “We want to do something like this.” For me, when Kid A came out, I only heard it through my daughter because of my age. I haven’t listened to it that much, and I don’t know it that well, but I felt like it went over a lot of ground that I had heard a lot of people do before, even though I still enjoyed it. I saw it as something that people thought was revolutionary, because they hadn’t heard some of the stuff that might have been 20 years old. But that’s whatever.

World Saxophone Quartet: “I Heard That” (1980) from Revue (Black Saint)

Horvitz: World Saxophone Quartet?

SW: Yes.

Horvitz: I would guess because most of the saxophone quartets I know . . . it would be the vibe of these guys.

SW: How would you describe the vibe?

Horvitz: Well, I think compared to the other saxophone quartets, and it’s a pretty small group, there’s just a more African-American attitude, I think, than Rova or the Your Neighborhood Saxophone Quartet, which is a really nice band. Is this early? [Very high note sounds] Well, there, you heard Julius [Hemphill] right there, on that note. But there’s that sense of, you know, more blues.

Bill Frisell: “Is It Sweet?” (1994) from This Land (Elektra)

Horvitz: Sounds like Bill. Well, we can’t talk about Bill because he’s too close a personal friend, to me for ages, and to Tucker, you know, for a solid age now, and Tucker’s been working with him tremendously. The thing about Bill is that he’s not only a great player, but he actually changed the way people think about electric guitar, and you can’t say that about that many people.

SW: When you were talking to musicians about playing on Mylab, how did you approach them? Obviously, you’re friends with Frisell, but in a situation like that, do you have set parts or ideas? Or was it more improvisational?

Martine: We knew places that we thought he could bring something to what we’d started, but there weren’t parts written out.

Horvitz: For example, Skerik on a couple pieces, I didn’t have parts written out, because it was like a riff, and he laid down some parts. I don’t think Bill laid down any parts, although he could have chosen to. And we did it the modern computer way, you know: Keep recording and worry later. But my favorite Bill solo on the record [on “The Big Crusher”], a lot of people think isn’t a guitar solo, because we messed with the sound so much. And then Tim [Young] takes a solo right after him that sounds more like a regular guitar.

Martine: But it’s Bill, unmistakably.

Horvitz: Yeah, you know, Bill playing keyboard. No one would ever play that way, just rhythmically.

Triple Threat: “Morning Showers” (2003) from Many Styles (Fat Beats)

Martine: [after a few seconds] It’s going to jump into a hip-hop beat, isn’t it?

SW: Yes. This is three scratch DJs from the Bay Area?one of the better turntablist records I’ve heard. Do you consider Mylab more of a cut-and-paste style album than you’re used to doing?

Martine: I’d say to an extent, on the various projects we’ve worked on [together], there’ve always been fairly known boundaries, because it’s either another artist’s work or it’s Wayne’s compositions or something. We’d gotten into little elements of that but never dived completely into it, and we did on this one.

Horvitz: Obviously, Tucker’s worked that way before. Actually, there was an initial conversation we had where Tucker was kind of surprised I hadn’t made another record in a while that was like some of my solo records I made in the late ’80s. This was really pre-Pro Tools and pre-computer cut and paste, so I’ve done a lot of stuff with sequencing and then bringing in people to play over stuff and some tape editing, but mostly it was still constructed that way. Lots of people were doing what I was doing, but not with the kind of music and the people I was. I also used a lot of things where I used drum machine and live drums [together]. I made a couple of records like that, and Tucker had heard those records before we met. I was flattered he liked them, and he said, “You should do something else like that.”

I used the computer a lot, but it proved the adage about computers, too. In one sense, you can do all these things, and, on another level, it’s, you know, unbelievable?it just takes forever. I remember very close to the end of this, I was like, “Forget it, I just want to go play again.” But it’s also this incredible asset, and what a whole generation of people considers the way to approach music, how they make music.

Martine: It’s through that process that Wayne taught me the expression “option anxiety.”

SW: That’s a great phrase.

Horvitz: Which I learned from an engineer in New York even before Pro Tools came along. He was saying even with 24-track recording and how many reverb settings you can have and automated mix-down. Well, that’s about 1 percent of the option anxiety you can get into now with plug-ins and cut and paste. You have to be very patient and a certain kind of person to do that, and I can only spend so long in front of a computer

SW: A few years ago, Brian Eno wrote an essay on that topic, although he didn’t use the term “option anxiety,” talking about how computers have essentially crippled music making because of what you’re describing.

Horvitz: That’s great, because it’s such an irony that he, of all people, would say that. Because, of course, as a kind of initially improvising musician, I almost felt that Eno was guilty of that 20 years ago?it was too thought-through, too produced, even though I enjoyed a lot of his work. It’s also just telling about that at his age he’s like, “Enough already. OK: 48 tracks, 12 sends, I love it.” Look at how he works and Daniel Lanois works?they’ll put up eight different faders each with a different delay time. Well, even to George Martin that would have been option anxiety, but now [Eno has] reached his threshold. Some of these kids who make this stuff, it’s partly just that they’re 21, that they can sit in front of a computer for 12 hours a day. It’s hard.

George Lewis has worked with the A.A.C.M. and is associated with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, but also associated with people like [John] Zorn and Bill?I’ve worked with him, and he’s done a lot of software writing for improvisation. But his position is that by the age of 40 one should stop writing new software because you just can’t handle it anymore. And he’s past 40, and he’s written amazing software.

Jackie Mittoo & Randy’s All Stars: “Jackie’s Theme” (c. 1972) from 300% Dynamite! (Soul Jazz, U.K.)

Horvitz: Is this the Meters? No, it’s pretty obviously Jamaican.

SW: If it gives you any help, it’s the organ player’s record.

Horvitz: Well, It sure sounds great, whatever it is.

SW: It’s Jackie Mittoo.

Martine: Is it all instrumental?

SW: Yes. It’s pretty obviously Meters influenced.

Martine: I need to track this one down.

Horvitz: That’s great. It’s at least worth noting [that] it’s not a jam, you know, and that is so cool that way.

SW: No, it’s just a straight groove with very little embellishing.

Horvitz: And he uses an organ and it’s the lead instrument. This is his record. This period of Jamaican music is the ultimate analog processing, tripping with the sound of the board and stuff. As much as we did with the computer, we tried to keep that kind of spirit, you know, [mixing] stuff on the fly, even with the studio at the end that we worked at, unlike the studios we started the project in, we just kept wanting to put, like, a stomp box in the insert, and the guys were like, “Yeah, we’ll have figure out how to do that.” When it should be the obvious thing to be able to do.

Martine: Well, you spent $300,000 on a studio and you don’t want to use, you know, a crappy spring reverb that costs $40.

Horvitz: And the answer is, yes, we do.

Ornette Coleman + Joachim Kuhn: “House of Stained Glass” (1997) from Colors (Harmolodic/Verve)

Horvitz: [The recording opens with a minute and a half of solo piano] I’m thinking of all the people it’s not.

SW: That’s an interesting list. Who’s on it?

Horvitz: Well, I don’t think it’s Keith Jarrett, and it’s not Paul Bley. It’s a relatively modern recording.

SW: It’s seven years old.

Martine: Is the performer the composer?

SW: Yes, but the composer hasn’t entered yet. [Saxophone enters]

Martine: This isn’t Ornette . . .

SW: It is Ornette.

Horvitz: Right! With the German pianist. The piano throws you off. I’d forgotten he’d done this project?Ornette’s legend is that he’s never used a pianist, and this is the only thing he’s ever done with a piano. [Kuhn] is one of those guys whose style I wouldn’t recognize right off. Ornette, like Zorn and a lot of other alto players, has that kind of sharp intonation, and it’s a little weird with piano, but it’s also amazing, particularly because it makes Ornette sound more in the straight-jazz tradition. I actually heard this duo live in Rome, outside, and it was a really interesting reaction. Italians are really opinionated about American jazz?they were either for it or against it. People were for it and people were against it.

Martine: Was anyone yelling “Judas”?

Aphex Twin: “Flim” (1997) from Come to Daddy (Warp)

Horvitz: Björk?

SW: Not quite. It’s a producer. It’s instrumental. It’s a pretty obvious name.

Martine: That just makes me more scared to guess. [Pause] Aphex Twin?

SW: Right. This is the song the Bad Plus covered on their last record.

Martine: Is this from I Care Because You Do?

SW: No, I think the one after that, Come to Daddy, the eight-song EP.

Martine: Right, where they’re almost songs and there’s way more melodic content. It’s a beautiful record.

SW: You talked about that a little bit with the Triple Threat song, but had you been listening or paying attention to this kind of stuff in relation to Mylab? Obviously, Tucker has worked with Land of the Loops . . .

Martine: Like Wayne said, we really never discussed any sort of specific direction except, you know, we’ll put some ideas in the computer, start chopping them up, making just a rough form and bringing some people in and developing the pieces out of that?but I think some of these influences show.

Horvitz: Well, we really enjoyed, like, all this stuff. We start with cutting up the drum sounds, processing and speeding up the drum sounds. Some of this stuff is kind of up in the air, you know?I don’t go to the store and purchase it, but I hear it on the radio, I hear it other places, or people play me stuff, and then I’m going, “Oh, so that’s how it’s done. It’s great.” So we’d go there in our own way. Basically, in conversation, Tucker and I are essentially sarcastic about all music, and in point of fact, neither of us are that interested in being smart, but in pleasure and emotion. It’s not something we do, say, “Let’s take these influences and put them together.”

SW: No, I can’t imagine any musician really works like that.

Horvitz: Oh, there are a few. I won’t name names. [Laughs]

SW: I also wanted to ask about the Bad Plus. They seem to be dividing opinion among jazz people more than just about anybody in the last few years.

Horvitz: I have a really bad confession to make: I’ve never heard a note they’ve played. I’ve read about them, and I keep meaning to hear them, and I was on the way to hear their gig one night and something came up at home, and I didn’t make it.

SW: That’s much better than either extreme, really.

Martine: When I heard about this new jazz trio covering Nirvana and all that, I was sort of bracing myself to not like it at all, but when I heard it, I must admit, I enjoy that record. What’s a little bit unique about them is that for a jazz record, they really chose to use the studio also as an integral part, and they’re adventurous with their sound?they’re not afraid to manipulate some of their sound. It’s just rare that you have jazz musicians that sense of ability combined with . . .

Horvitz: Well, I don’t quite agree, because it depends on what you mean by jazz musicians.

Martine: Not so much a jazz musician as much as a jazz record. It’s a trio playing jazz songs with a no overdubs, as far as I can tell, but there’s things that will get faded out with, like, delay spilling over, and things get cross-faded in interesting ways or the drum track will be really squashed on one song.

Horvitz: It comes and goes. If you really want to get into it historically, I mean Lennie Tristano overdubbed piano stuff in 1956 and Charles Mingus replaced bass parts on a live Charlie Parker record. Look at Teo Macero, who edited all those Miles Davis things like crazy.

Martine: Not to say that it hasn’t been done . . .

Horvitz: What I think is going on is that there was a real period of conservatism in the ’90s?and the ’80s, even more so?and suddenly the jazz world split into two camps. And then you’ve got the people, myself included, who might end up in the jazz bins, quite obviously, I’m not even sure why. It doesn’t make sense to me.

SW: Another thing that’s been happening that I don’t think has divided opinion at all, but the Thirsty Ear Blue Series that Matthew Shipp has been putting together. Just doing this now, I realize I should have included one of those tracks. Have you paid much attention to those?

Martine: Like the one he did with DJ Spooky?

SW: Yeah.

Martine: That’s the only one I’ve heard.

Horvitz: I mostly know [Shipp’s] work before that and I’ve only heard about it?I haven’t really heard it. And I’ve heard Spooky’s work and I’ve worked with him once, but I think it seems like an obvious collaboration. I think that Sonic Youth deserves a lot of credit because, in a funny way, they came along first. I shouldn’t say first?they came along and said to William Parker and to Matthew and those kind of people, “We’ve been into your kind of music all along, and you may not know it, but it really influenced our music.”

SW: There was an Invisible Jukebox in The Wire magazine a few years ago with Yo La Tengo, and they played him an Albert Ayler cut or something, and the interviewer asked them something like, “How do you account for the American rock underground suddenly being into free jazz?” and Ira Kaplan said, “Thurston Moore.”

Horvitz: Except that I also think that they’ve been into it off and on without people realizing it. You have to remember when the Byrds did “Eight Miles High” (1965), they said they did it because of listening to John Coltrane. To be the old man here, once again it seems like all the stuff just keeps coming around. All the psychedelic bands were listening to Ornette and Cecil and Coltrane in 1967.

Martine: Well, Sun Ra, too. I really, I hear the Sun Ra influence hugely in that Matthew Shipp/DJ Spooky [record].

Horvitz: But in the ’60s [rock musicians] were definitely listening to Coltrane, and they were listening to Ramsey Lewis, too.

SW: I think the punk schism sort of ruptured that, because there wasn’t necessarily a straight line from that stuff operating as an influence on rock for a long time.

Horvitz: Yeah. It’s interesting, there was that whole thing with having the two-minute song, and that wasn’t working with free jazz.

Arto Lindsay: “Erotic City” (1997) from Mundo Civilizado (Bar/None)

Martine: [Immediately] Arto. I know this record. The bass sounds great.

SW: It’s Melvin Gibbs playing bass.

Horvitz: Melvin does great work.

Horvitz: It’s interesting, my daughter loves Prince, and she says that among her friends, a lot of them put him in the same place as, like, a Michael Jackson. It’s too bad: Just from a production point of view, but I mean [in] everything, Prince was like the next Sly and the Family Stone. He just completely reinvented music, producing, you know, his songwriting is great. My wife, for Christmas, gave me the flip side of “1999,” “How Come U Don’t Call Me Anymore?” I’d been looking for this thing. I used to play in this blues band at this bar and it was on the jukebox, and I could remember this song, and it was just so unbelievable. That night I must have listened to it like 50 times.

Arto is one of those guys who . . . not many people know [about Lindsay’s late-’70s no-wave band] DNA. I saw their last two gigs?they played for two nights in a row at CBGB?and, you know, Tim [Wright] actually knows how to play an instrument, but Ikue [Mori] is not a drummer you’re gonna go call a drummer, and Arto’s not a guitar player you’re gonna call a guitar player. There’s the issue of aesthetics as opposed to ability?just that both those people, Ikue and Arto, have such a strong aesthetic and [were] able to use so little to make so much . . . that band was unbelievable, and never recorded well. No one could hear what they sounded like live.

Martine: Really? I was pretty blown away by the records.

Horvitz: Well, part of it was just the sound system at CBGB. But Arto has just gone on to make all this incredible music, with other people’s music, with his music, and his singing is totally unique. I’ve worked with him a lot and he’s a funny guy, just hilarious. The Brazil connection’s there ’cause he grew up there and spent some of his childhood there, and he speaks Portuguese. It’s just such a funny transition from DNA, and yet he made it work. It didn’t sound “eclectic.” It sounded Arto.

Sugarman 3 & Co.: “Funky So-and-So” (2002) from Pure Cane Sugar (Daptone)

Horvitz: Is that another instrumental?

SW: Yes, it’s another organ record. It’s a Brooklyn band who are part of the whole axis around Antibalas Afrobeat Orchestra. The whole thing is designed to sound and look exactly like a late-’60s record, the engineering and everything. They played at the last Bumbershoot.

Martine: I bet they’d be a fun band to see live.

Horvitz: It sounds great. It’s interesting, though, that the thing that’s not like James Brown is, it’s got like a bit of the New Orleans thing and the Memphis thing, but it’s got a bit of the twangy thing in it, you know, in the guitar.

SW: Rather than the hard chanking sound?

Horvitz: Yeah. Something the two of us share a lot, I really like that intersection of?you know, that famous story where Aretha went to Muscle Shoals and thought she would be recording with an all-black band, and it was an all-white band. It’s this kind of intersection, ’cause these guys played country music, too. You hear that in the Meters, that they hear country music.

SW: With Zony Mash, you were doing a version of Meters-style funk.

Horvitz: Why would I bother . . . no, I would [say] the worst thing about Zony Mash is that the Meters ever came up. The point about the Meters was just an indication [that] I was gonna write my music for that instrument, because I had never put a band together around the organ. Originally, I was sitting there and I had two minutes to do a press release, and I thought, “OK, cool.” We covered a Meters tune a few times, but attempting to play like the Meters is a real dangerous thing to do.

that dog.: “Minneapolis” (1997) from Retreat From the Sun (DGC)

Horvitz: Is this Sleater-Kinney?

SW: No.

Martine: I don’t think I’ve ever heard that voice?I really like it.

SW: It’s that dog. Petra Haden was in the band, and Tucker worked on her duo record with Bill Frisell last year.

Martine: Which was a great experience, watching her work. She’ll just kind of lay on the couch until it’s her turn, and then she’ll ask if you have 10 tracks and she’ll go in there in about three minutes with the string section and do her parts. I haven’t listened too much at all to this band. The vocals are right up front, which is a little unusual. She’s not the singer in here, is she?

SW: No, that’s Anna Waronker. They were on Geffen, and I think one reason the vocals are way up front was because they were sort of trying to get on the radio.

Martine: I just realized my good friend?that loves that dog.?is from Minneapolis, too. We’ve got to start writing songs about every major metropolitan area. Mylab perform at the Triple Door at 7:30 p.m. Mon., Feb. 15. $20.