It’s not every national creation story that frankly acknowledges innocents will die in the struggle for colonial liberation. To show a young Algerian shed her veil, cut her hair, paint her face, and dress as a secular Frenchwoman in order to place a bomb in a crowded cafe takes some guts on the part of the filmmakers. Indeed, the reissued, refurbished 1965 The Battle of Algiers (which opens Friday, Feb. 13, at the Neptune) is a great, gutsy film and particularly essential viewing as our troops continue to occupy and die in Iraq.

The Algerian FLN guerrillas who sought to cast off 130 years of French colonial occupation in the 1950s are not exactly equivalent to today’s rump resistance fighters in Iraq. But the anticolonial feelings and resentments engendered by Western occupation, no matter of what duration, are exactly the same.

Directed by an Italian Jewish ex-Communist who fought Mussolini (Gillo Pontecorvo) and funded by the FLN, which has been the ruling party in Algeria since the French finally withdrew in 1962, Battle lays out Algeria’s history step by bloody step, re-created in the style of a tense, breathless, two-hour neorealist newsreel. It begins with a handful of FLN fighters hiding in a wall while French paratroopers prepare to dynamite them in 1957, then flashes back to the roots of the insurrection three years earlier. Titles supply the dates of significant bombings, battles, and brutalities; voice-overs come from FLN communiqués, French government edicts, and journalistic dispatches.

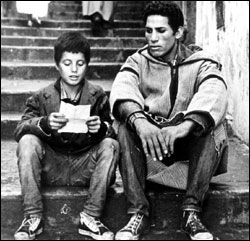

A FLN guerrilla, Saadi Yacef, plays rebel leader El-hadi Jaffar, while his right-hand man, Ali La Pointe, is played by Brahim Haggiag, an illiterate Algerian peasant. Director Pontecorvo spotted Haggiag in a marketplace and cast him for his unforgettably fierce face. When, before joining the FLN, petty hustler Ali is fleeing the cops and tripped by a laughing French youth, his look of contempt and humiliation burns a hole in the screen. He’s not just a future rebel getting off the ground to strike the occupier; he’s all of Africa, all the Third World, all humanity.

Battle is the ultimate cowboys-versus-Indians picture where you root for the Indians, no matter how many cowboys they shoot in the back. It’s history, but it’s history made exciting by chases and shoot-outs among the vertiginous, Escher-like stairways of the Casbah. Even as you dread the rebel bombing of French civilians (children among them), the old movie device of a ticking bomb and an uncertain delivery person makes for Hitchcock-level suspense and guilt. You want these female bombers to succeed, and you don’t. Other FLN strategies are fascinating and foreign, too: Intricate assassinations are aided by veiled women who, at the last second, pass pistols to the hit men—then retrieve them in the chaos, safe from pat-down searches by the clueless French. The score by Ennio Morricone juxtaposes Bach with propulsive North African drumming and ululation; these are two cultures at odds musically as well as politically.

The sole professional actor in the film (Jean Martin) plays Col. Mathieu, who’s completely undeluded about the nature of his mission. Reporters ask whether his men torture FLN suspects for information, and he lays the blame squarely back on the French public, where it belongs. “It’s a vicious circle,” he says. If France wants to retain Algeria, this is the moral price that will be paid: beheadings, bombings, and torture by blowtorch, drowning, and electrode. Vive le republique. Pessimistic professional soldier Mathieu references Indochina and anticipates Vietnam. (“Why are the Sartres of the world always on the other side?” he asks.)

A final coda shows the spontaneous street demonstrations that finally expelled the Gauls five years afterward. Yet what’s saddest about Battle is its unstated postscript: Four decades later, Algeria is a mess, not a democracy; the FLN has deteriorated into a fascist ruling party that opposes free elections and only empowers Islamic fundamentalism. The revolution has succeeded, then failed, just as it will likely do in Palestine and Iraq. (Iran supplies the best bellwether of such discontent, as the Muslim gerontocracy of ’79 teeters ever closer to obsolescence.) Like it or not, Israel remains the only democracy in the region; though, like the French seeking to cordon off the Casbah, the Israeli effort to seal the West Bank and Gaza Strip is also futile. Meanwhile, France worries about immigration from its impoverished, unhappy former colonies. And America worries about getting fat—never mind the suburbs and SUVs that make us that way and tie us so inexorably to the Middle East. (Car . . . bomb—funny how those two ideas are related.)

Here are some of the final realities that stick with you from this brutal, uncompromising classic. Terrorism works. Torture works. Free societies will always give in to violence—either by acquiescence or by responding in kind. Nobody’s hands are ever clean, on either side of the conflict. A woman will kill a child, then later even forfeit her own life, for the sake of a cause, however imperfect. Worse, her life—and many others—will have been spent in vain. No cause is worth it, but there will always be another cause to die for, plus a long line of martyrs waiting for the glory of joining that eternal procession. The actual Battle of Algiers may have been a Pyrrhic victory, so far as French history is concerned; as a movie, it’s the future.