Like a visionary archeologist, Ellen Gallagher digs up dirt on the past, exhuming racial signifiers and cultural artifacts; then, through her art, she transforms them into new systems of layered meanings. Moby Dick, African mythologies, magazines, and minstrel acts are some of the inspirations for this process of metamorphosis. She has been quoted as saying she is “interested in the way materials manifest meaning.” At the Henry Art Gallery, her “Preserve/Murmur” exhibit is composed of three separate yet obliquely related series of work. In each, she employs distinct materials in ways that give new meaning to the term “skin deep.”

Upon entering the gallery, the disconcerting sounds of “Murmur,” a set of five films, strikes one immediately. Endless loops revolve on each projector with a mechanical buzz, like the whirring sound of cicadas in the Southern summer night. Four of the five films are hand-drawn animations; one involves spiritlike female figures who spin and glide in sync across the screen in a process of perpetual evolution. Their cloud-shaped afros unfurl into wings, which morph into tapering, mermaidlike bodies.

The fifth film is a clip of a found and altered black-and-white sci-fi movie about alien possession. The alien, a giant cyclopean eye, overcomes each victim by pointing its gaze with a power akin to Medusa’s. Gallagher comically conveys each character’s experience of alien possession by collaging wild sulfur-blond hairdos onto their heads and blank zombie stares onto their gaping eyes. Humor mitigates the melodrama of the film and allows Gallagher to make a serious point about self-alienation caused by outside forces. All five films are roughly executed and grainy; as with all of Gallagher’s work, they usually assert that they, like all cultural codes, are constructions.

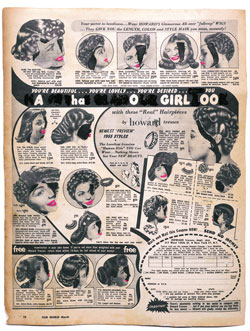

Alienating conceptions of beauty, particularly female beauty, were dispersed through mid-20th-century wig and skin-lightening ads found in African-American publications like Our World and Ebony. In a series of collages titled “Preserve,” Gallagher uses old pages from these and other magazines, then vandalizes them with toy eyes and plasticine lips (suggesting the exaggerated facial features of blackface and minstrelsy), pomade, and pencil and ink.

In pieces like A Ha O Girl Oo, Gallagher galvanizes the absurdity inherent to wig advertisements that promoted the sale of over-the-top, often straight hair. Though manifestly directed at blacks, such ads carry a latent message that whitewashes race. Gallagher then disfigures the models whose smiling faces were meant to sell products of literal disfigurement. (In the same way, the artwork’s title comes from altered mid-’50s ad copy that once read, “You’re beautiful . . . you’re lovely . . . you HAVE that GLAMOUR GIRL LOOK.”)

As the underlying ad places the word “real” in quotation marks, Gallagher effectively puts sarcastic quotation marks around the entire ad by defacing it. All the collages in this series similarly use satire to examine the racist notions of beauty revealed in these advertisements.

The exhibit’s third section, “Watery Ecstatic,” is my favorite—so why is it omitted from the exhibition title? It consists of a series of carved drawings in which Gallagher uses a knife on heavy sheets of paper to etch a realm of sea creatures and submarine terrain. They’re embedded like scars or fossils into the paper. Some of these sliced drawings include washy watercolor stains and lines that tangle and flow like seaweed or coiled snakes. The intricate patterned scales of Gallagher’s fish and eels are as precisely rendered as those found in Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which depict a “floating world” of idle, everyday pleasures. Gallagher’s world floats, too, but in a space that is fathoms deep, where pleasure is flayed with pain.

The exquisite delicacy and implied violence here are sublime and, from a distance, subliminal. That Gallagher’s imagery must be approached and discovered upon close inspection is conceptually brilliant. It subtly expresses that most things in life, from history to the everyday, must be examined up close in order to be understood. Moreover, Gallagher’s work shows how varying perspective and proximity constantly change one’s vision of the world. That glamour girl has come a long way.