THE SLOGAN on the Web site of Dr. Kevin Elliotts private practice is no judgment, no guilt. But the medical director of the recently closed Seattle Gay Clinic is about to be judged, and he has pleaded guilty in a court of law. Elliott, 50, is under investigation by the state medical board and has a criminal history of domestic assault. But he is still a licensed doctor with an office on Capitol Hill that is listed on a Web site called Kink Aware Professionals: We want to hear what you have to say and cannot be shocked. If you do [shock us], then we might try it too. At least until recently, when Seattle Weekly inquired at the Gay City Health Project, Elliott was a candidate to be medical director of that organization, too. Meanwhile, the doctor faces possible loss of his medical license, or other sanctions, for allegedly assaulting four people, three of whom were former patients.

In late November, the Washington Medical Quality Assurance Commission, more commonly known as the state medical board, brought charges against Elliott that included the assaults and other alleged violations. In each assault, Elliott is accused of injuring the victims, one of whom was a boyfriend at the time and another of whom was his father, according to the medical board. Elliott pleaded guilty to two of the assaults last summer in criminal proceedings. Simply having been convicted of a gross misdemeanor could be a violation of state regulations. The medical board also is alleging that Elliott verbally threatened another person, whom the state will not identify, in 2001. I cant recall another case like this one, says Lisa Noonan, disciplinary manager for the Medical Quality Assurance Commission. She has worked for the medical board for 13 years. It regulates the licensing and standards of practice of medical doctors in Washington and each year fields about 1,000 complaints. More typically, the board investigates allegations of negligence, keeping improper patient charts, and sexual contact with patients.

Elliott is still free to practice medicine, pending a hearing before the medical board April 30 in Tumwater. He did not respond to repeated requests for comment or to questions faxed to his office.

Seattle Gay Clinic, where Elliott was medical director, closed on Dec. 31. Founded in 1979, it provided HIV and sexually transmitted disease screeningservices that were absorbed by Gay City Health Project, according to Fred Swanson, that organizations executive director. Swanson says that Gay City had been in discussions with Elliott about signing on as medical director, but he says he was unaware of the criminal and medical-board charges against Elliott until Seattle Weekly inquired about them. He declined to comment on whether they would affect Elliotts job prospects. Many AIDS and HIVpositive patients, Swanson says, are satisfied with Elliotts private practice.

Medical board regulations governing the conduct of physicians in Washington open a doctor to potential discipline if he or she commits an act of moral turpitude, is convicted of a gross misdemeanor or felony, or abuses a patient or client, among other things. Among the states charges against Elliott, outlined in a public record of the case, are alleged violations of the doctor-patient relationship. They cannot have any kind of contact with patients except in a patient-physician relationship, says Noonan.

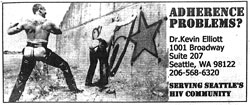

ONE OF THE more bizarre allegations against Elliott involves an advertisement for his practice that ran in the Seattle Gay News in 2000. The state medical board record describes the ad as depicting Elliott in a sadomasochistic scene with a patient. Says Kelly Fryer-Edwards, a medical ethicist at the University of Washington School of Medicine: Wow, involving patients in your adsthats really crossing some boundaries. Fryer-Edwards and other medical experts say that the reason for limits on contact between doctors and patients is to prevent against physicians exerting undue influence over vulnerable people.

As for the other charges, the medical board does not name the alleged assault victims in the publicly released version of the record, although it does say that three of the four were former patients. One incident, however, involving two of the former patients, is a well-documented King County Superior Court case in which Elliott pleaded guilty. According to documents filed by the King County Prosecuting Attorneys Office, on the evening of Dec. 6, 2002, Elliott and his then-boyfriend, Joel McClanahan, 37, were drinking and discussing their relationship at a condominium. They had an argument. McClanahan left the residence and went to visit a friend, Bruce Martin, 48. At approximately 12:30 a.m. on Dec. 7, Elliott went to Martins home and knocked on the door. Martin opened it, and Elliott forced his way into the house without invitation, the court record says. Martin was slammed against a wall by Elliotts entry, and he suffered a contusion to his left elbow. Elliott then went upstairs to the kitchen, where McClanahan sat on a barstool. Elliott knocked him off the barstool and onto the floor.

The doctor, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, next began punching [McClanahan] repeatedly in the head while McClanahan was on the floor, according to the court filing. Martin tried to call police, but Elliott knocked the phone to the floor, breaking it. Elliott left the house, with McClanahan following. Elliott pushed him up against a fence and then punched McClanahan in the left side of the head. Seattle police later reported that McClanahan had a cut nose, a cut on the left side of his head, and numbness and a loss of hearing in his left ear, according to the court filing. Later treated at a hospital, McClanahan was diagnosed with a ruptured eardrum.

Arrested later that morning by police, the doctor told police that McClanahan and Martin must have injured one another. Elliott was held five days in the King County jail for investigation of second- and fourth-degree assault involving domestic violence. He pleaded guilty last June to two counts of fourth-degree assault, a gross misdemeanor. Elliott was given a one-year suspended sentence and two years of probation and was ordered into a state-certified domestic violence program.

Kevin Elliott as medical director of the now-defunct Seattle Gay Clinic. |

That wasnt the first time Elliott was accused of assaulting someone who turned out to be a former patient. In 1996, he allegedly caused significant injury to someone who did not file a police report, according to the medical boards records. Noonan, the boards disciplinary manager, declined to identify the injured party, citing confidentiality laws, but the boards record says this person, too, had been a patient.

And on Feb. 8, 2003, Elliott allegedly committed another assault, again causing injury, according to the boards charges, although it was not a patient this time. Noonan says the victim was Elliotts father. She declined to provide his name, citing confidentiality laws. The person declined to press charges after contacting police, according to the boards charges.

IN LIGHT OF all this, Pat Kuszler, a law professor at the University of Washington with expertise in medical licensing, says Elliott might have a hard time keeping his license. If its a criminal act perpetrated on another human being, thats going to have a negative impact on his ability to maintain a license, she says.

Noonan says the board initially received a complaint about some of the assaults in December 2002. Asked why a doctor who later pleaded guilty to assault would be allowed to continue practicing medicine, Noonan says the medical board investigation was not completed until last fall and that the board was unable to take up the case until this spring.

Sidney Wolfe, a longtime critic of medical boards around the country and of Washingtons in particular, says thats nonsense. A physician, Wolfe is director of Public Citizens Health Research Group, a Washington, D.C.based watchdog. If you were on a medical board, this might rise to the level of some sort of emergency, he says, speaking of doctors committing crimes in general. It would seem like this should be something that would require urgent action right away instead of waiting while the person is practicing with no restrictions on their license and possibly continuing to do damage to patients. This sends out a strong signal that the Washington medical board is not doing a good job of protecting the public.

THE CHARGES LODGED by the state are not the only recent trouble for Elliott. On Oct. 23, he settled a lawsuit for medical negligence. Delmar Adkins, a patient of Elliotts, had alleged that the doctor improperly handled his case of prostate cancer. Noonan reports that Elliotts insurance carrier recently filed notice with the board indicating that it had settled the case and paid an undisclosed amount of money to Adkins.

Elliott also ran into legal trouble in 1995. That year, his marriage to a doctor named Valencia Elliott, with whom he shared a practice in Federal Way, was dissolving. In a proposed protective order, his wife alleged repeated domestic violence. Elliott denied most of her allegations but did admit to once punching his wife on the arm and to physically throwing her out of their Federal Way home, according to court documents.

Noonan says Elliott faces a range of potential discipline, including loss of his medical license, suspension of his license, fines, or simple censure. She says that the medical board commonly orders doctors to undergo training and pay fines as high as $2,000 per charge. This case, she says, might be different. They may have to get creative here, she says.

With reporting by Virginia Donald and Zana Bugaighis.