Every obituary tells a story, but architect Louis Kahn’s 1974 death made the front page of The New York Times without divulging much about his life at all. His modernist works spoke for themselves. That’s how a designer wants to be rememberedeach building serves as a monument to its maker. But there’s more to a man than bricks and mortar, as demonstrated in the documentary My Architect: A Son’s Journey (which runs Friday, Jan. 30, through Thursday, Feb. 5, at the Varsity). As you’ll gather from the title, it’s directed by Kahn’s son, Nathaniel, previously a filmmaker but not a guy who knew his father much better than the average Times reader.

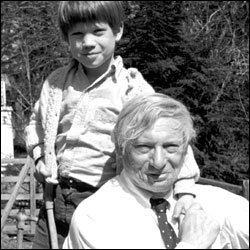

The reasons for this are both simple and complicated. Louis Kahn dropped dead of a heart attack when Nathaniel was only 11. They didn’t live together because Louis wasn’t married to Nathaniel’s mother. He had a wife and daughter, then another daughter with a girlfriend, then Nathaniel with another girlfriend. You’d call the famous Yale and Penn prof a Don Juan, only he was so clearly anything but: short, rumpled, chronically broke, and facially scarred from burns suffered during his childhood in pre-World War I Estonia.

If you’re unfamiliar with Louis Kahn’s work, the Oscar-nominated Architect serves as an adequate primer on the subject. Though the film’s putatively about him, it’s more about Nathanielas the subtitle implies. The documentary represents his five-year quest to learn more about his itinerant dad, with Nathaniel as narrator, interviewer, and tour guide from Philadelphia to California to Bangladesh. In this way, unavoidably, Nathaniel becomes the movie’s star. What with all the Ken Burns-ian photomontages (Ellis Island, the shtetl, famous buildings, etc.), and Nathaniel saying things like, “I felt I was getting closer to my father,” I almost walked out of the screening at SIFF last year to avoid the expected final swamp of hugs, healing, closure, tears, and twinkly, heart-tugging piano music.

BUT I STAYED PUT, and Architect keeps at least one foot out of the sap because Nathaniel, too, is aware of the film’s (and his own) mawkish tendencies. He hugs, but sheepishly. And though Louis is more of a ghostly presence here (seen and heard only in a handful of clips), he helps haunt away any easy reassurances and resolutions. He refuses to be known, in a sense, beyond his workwhich is perhaps why he gamboled between his three families and often slept at his office or on the road. “A nomad,” one colleague calls him, and another”a mystic.” Selfish is more like it. “He could juggle people’s lives, and it didn’t bother him,” says a co-worker.

Among these high-level talking heads are architects Philip Johnson, Frank Gehry, Robert A.M. Stern, Vincent Scully, and I.M. Pei. But Nathaniel also grills his mother and seeks out his two half-sisters, then stages a genteel, Geraldo-style sit-down where he asks them, “Are we a family?” And inevitably, after a lot of reverential gazing at buildings, Nathaniel’s pilgrimage leads him to the East, where he consults with gurus who declare Louis could “discuss matter in spiritual terms.” Perhaps those were the only terms he understoodthe abstract, not the personal or the familial. To his credit, Nathaniel seems by far the nicer, more well-adjusted guy, even if he insists on reconciling himself with a man who resisted every embrace.