“You have to decide. You have to convince yourself: ‘This is for me. This is what God wants for me.'”

It’s a September evening at the Christian Faith Center, a large evangelical church in SeaTac. The room is cavernous and bland, with a 1970s look about its green carpeting and green chairs. The preacher, though, is anything but bland. With his image broadcast on four screens above him, Pastor Casey Treat is a live wire: His thin frame, lit from above by bright red hair, is bursting with the energy and charisma that have made him the Northwest’s best-known televangelist. If the room needed any further enlivening, it is found in tonight’s topic for discussion. What Treat is saying God wants for usthe subject that has brought hundreds here for the $15-a-person “Kingdom Builders” seminaris prosperity.

“If you don’t have the right attitude,” Treat singsongs, “you can’t live a prosperous lifestyle. So we’ve got to get right in us. First of all, you have to believe, receive, and embrace the principles of prosperityfor you.” While the process he describes is spiritual, linking personal prosperity and God’s plan, it is also exceedingly practical. Treat talks about behaving like a winner just as successful football players do, talking on the phone with self-assurance, dressing for success by ironing your shirts.

Prosperity is a recurring theme in Treat’s ministry, and tonight the pastor has brought in a heavy-hitting speaker to back him up, someone with Old World authority: Rabbi Daniel Lapin. The Mercer Island rabbi, who preaches conservative politics along with Judeo-Christian ethics through his syndicated radio show (based at Seattle’s KTTH-AM) and his national, nonprofit group, Toward Tradition, has recently penned a book, Thou Shall Prosper: Ten Commandments for Making Money. In it, he writes that “God wants humans to be wealthy because wealth follows large-scale righteous conduct.” A polished performer who sprinkles his talk with one-liners like a scholarly Borscht Belt comedian, the suited, yarmulke-wearing Lapin explains to tonight’s crowd that money “is God’s gift for human interaction” because acquiring it requires people “to connect with as many people as possible, to be obsessed with the needs of as many people as possible.”

They’re a seductive duo, the charismatic preacher and the worldly rabbi, but their get-rich, self-help messages strike an odd note. Even if you see nothing wrong with making money, isn’t religion supposed to be about a higher purpose?

THE CHURCH AND YOUR CHECKBOOK

Perhaps, but the mixing of religion and money has a long tradition in this country, according to Patricia Killen, professor of American religions at Tacoma’s Pacific Lutheran University. She cites 19th-century preacher Russell Conwell, who became famous with a talk called “Acre of Diamonds.” Preaching on financial success has become ever more prevalent in the past decade or two and seems to be finding particular resonance in these tough economic times. Witness the runaway success of The Prayer of Jabez, a little book published a couple of years ago by an obscure Christian publisher in Oregon. Centered on a prayer that envisions a life of abundance, the book set a record for the number of copies sold in a single year.

Though its preachers don’t like the term, some call this notion that religion will lead the righteous to riches the “prosperity gospel,” or the “gospel of wealth.” It finds particularly receptive ears in the Northwest, according to Killenperhaps no surprise, given the strike-it-rich mentality that launched this former frontier. While she thinks Treat is probably its best-known practitioner, similar teachings can be found in a number of evangelical churches, where God is understood to be, in Killen’s words, “real and intimately involved in our life,” including our financial life.

Accordingly, there is a growing movement to offer financial ministries in church, not just to preach the gospel of wealth but to teach nuts-and-bolts tools for financial management: how to balance your checkbook, save for retirement, avoid debt. A foundation tied to Overlake Christian Church, the powerhouse of evangelical churches in Redmond, has spent many months planning a national financial conference set for next spring that it hopes will attract as many as 7,000 people, spur similar seminars across the country, and inspire new financial ministries among churches. Despite the religious overtones, such practical education has been deemed a public service by a host of government agencies and nonprofits that are working with religious leaders on the conference. Among them: the Social Security Administration, the U.S. Department of Labor, and the American Savings Education Council.

THESE RELIGIOUS TEACHINGS about finance aren’t always congruent. Ask David Bragonier, executive director of nonprofit Barnabas, which conducts financial seminars for churches, what is causing the financial crisis he thinks afflicts so many Americans, and his answer is succinct: “Greed.” Doesn’t that belief conflict with the prosperity gospel’s inducement to get rich? Bragonier, who has been reading Rabbi Lapin’s book, doesn’t think so. “There’s nothing wrong with wealth. It’s just how wealth is used,” he says, meaning that wealth used for God’s work is admirable.

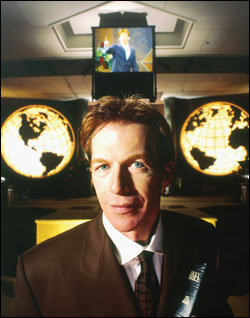

Rabbi Daniel Lapin doesnt shy away from the association between Jews and money.

(Tim Johnson / Strode McGowan Photography) |

Others find the prosperity gospel deeply troubling. “It’s a gross misreading of scripture and tradition,” says Robert Stivers, professor of Christian ethics at PLU. “It misses the whole center of Christianity, which is trust in God, not the acquisition of wealth.”

Ron Sider, a nationally known figure who critiques the evangelical community from the inside, heading a Pennsylvania-based organization called Evangelicals for Social Action, similarly thinks the prosperity gospel overlooks crucial passages in the Bible, such as those espousing the danger of wealth. “It’s a half-truth,” he says, “and half-truths are heresy. It’s seriously, fundamentally misleading Christians today.”

THE BIBLICAL BLUEPRINT FOR WEALTH

It is no less controversial in the Jewish community. When the University of Washington’s Martin Jaffe, a Jewish professor of comparative religions, is asked for his reaction to Lapin’s teachings on wealth, he replies, appalled: “He’s putting a Protestant gloss on Judaism.” Jaffe refers to Max Weber’s seminal book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which explains how influential Calvinist attitudes toward wealth stemmed from a belief in predestination. According to Calvinists, God chose the saved or the “elect” from the beginning of time, independent of any good acts people performed during their lifetime. The important question, therefore, was: Am I among the saved? And one crucial sign was your wealth. When the Puritans settled this country, that belief, combined with a determined work ethic, helped to create a rich soil for the rise of capitalism’s most successful society, one that reinforced a sense of self embedded in Protestant notions of personal salvation.

Yet whatever the influence of Protestantism on Lapinand it wouldn’t be surprising if there were some, because Toward Tradition is devoted to building bridges between Jews and Christians in Protestant-shaped Americait’s also true that Jewish scripture and teachings are less conflicted about wealth than those of Christians. The rabbi might have something when he presents himself as endowed by his heritage to teach positively about wealth, although his approach is anything but traditional.

“I don’t need to tell you that, historically, Jews have been pretty good with money,” Lapin says as an opening gambit to the Christian Faith Center crowd, which erupts in laughter. He acknowledges that some might think such a statement is anti-Semitic, but jokes, “If you’re circumcised, you can say anything.” More seriously, he knocks down long-held, often truly anti-Semitic explanations for supposed Jewish wealth. (Others argue that most Jews have not, in fact, been rich through much of their historythink of the shtetls of Eastern Europe.) It’s not that Jews cheat or belong to a secret network, Lapin says. Rather, “There is a Biblical blueprint” for wealth, “and Jews followed it year after year, century after century.”

THE BIBLE itself figures little in Lapin’s talk. More generally, the rabbi refers to God’s vision for a “life that is fulfilling and joyful and wonderful,” one in which God rewards those who interact with others in a positive way. And, he maintains, “Wealth is created when one person does something for another person.” He uses the example of a shoe-store owner who bends his knee to serve his client. “Don’t you think the good Lord is smiling?” Lapin asked. The client hands over $20 for the shoes (either Lapin must know of some bargain shoe stores or he hasn’t been shopping lately) and leaves happy. The store’s owner is happy. Everybody wins.

In his book, though largely devoted to self-help sections like one called “Control Your Physical Movements to Show Self-Assurance,” Lapin delves a little more into Jewish theology. He writes, for example: “The Bible emphasized the wealth of the Patriarchs; and along with other requirements, being rich was necessary for being chosen as a prophet during Biblical times.” He brings up the Exodus. Yes, the ancient Israelites were in a great hurry to leave their lives of slavery in Egyptbut not in so much of a hurry they couldn’t make time for the Lord’s instruction to gather silver and gold to carry with them to freedom.

Strangely, Lapin makes little of God’s covenant with the Israelites promising earthly rewards for righteousness, but it is a repeated theme in the Old Testament. A prime example is in the Book of Leviticus, when God tells Moses: “If you conform to my statutes, if you observe my commandments and carry them out, I will give you rain at the proper time; the land shall yield its produce and the trees of the countryside their fruit . . . you shall eat your fill and live secure in your land.”

So it’s not surprising that Rabbi Yechezkel Kornfeld, among other Jewish scholars, agrees with Lapin up to a point: “He’s absolutely correct.” The Torah, which is what Jews call the Old Testament, “does talk about material rewards for a righteous life.” However, Kornfeld, who leads Shevet Achim, the Orthodox synagogue on Mercer Island to which Lapin belongs, quickly adds that Jewish tradition holds that such material rewards are meant to enable people to continue the righteous way of life. That gold and silver that the Israelites brought out of Egypt? They were supposed to be used for instruments in building the Temple, Kornfeld confirms. “Clearly, the Talmud says the only reason God created gold is for the Temple,” Kornfeld says, referring to the ancient rabbinical commentary on the Bible that, for Jews, offers authoritative interpretation. Not literally the Temple, he notes, but “what the Temple represents: spirituality, nonmaterialism. . . . ” Gold, he continues, is to be used “so people’s lives will become better.”

Dave Bragonier assails the evils of greed. |

Though it primarily has positive associations, gold is also pictured in the Torah as a danger to one’s spirituality, Kornfeld says, mentioning a passage where the Israelites become “fat” and rebel against God. Moreover, Kornfeld asserts, while it’s true that the Talmud says material comfort is a prerequisite for being a prophet, it also says that “in order to be successful in Torah study, you should live a very simple material life.” Kornfeld suggests that the two statements are complementary: A modicum of material well-being allows concentration on higher matters, whereas too many material things can prove a distraction.

IN THE nondescript Mercer Island office building from which Lapin runs Toward Tradition, the rabbi takes a rather different tack from his own rabbi on the subject of materialism. “What exactly is this materialism that the world complains about?” he asks in his genteel accent, the product of his South African roots. If it means being able to travel by car rather than horse, to have a choice of different soaps, to go on the Internet and buy a book, then he says he’s all for that. Of course, he concedes, “if materialism is an ideology that things matter most, then that’s completely contrary to Judaism.” He doesn’t seem to think that’s a pressing problem.

And what of using one’s wealth for the symbolic Temple? Lapin does make a point of stressing the biblical injunction to charity, noting the tithe one is supposed to make, equivalent to 10 percent of one’s income. But clearly that’s not his primary concern, or the raison d’괲e of money, in his viewhe didn’t, after all, call his book “How to Help Others.” He called it Thou Shall Prosper. In fact, in his book, Lapin urges people to give away money, “because it is one of the most powerful and effecting ways of increasing your own income,” in part because it increases your network of people with whom you can later do business.

Lapin is on a mission to debunk what he calls the “mushy indictment of Western traditions of capitalism” that he thinks have been fueled by “conventional rules of religion” hostile to wealth. The rabbi’s version of religion is that making money is inherently good, and it has made him a popular guest lecturer at both synagogues and churches. That Lapin himself has had serious money problemshe declared bankruptcy after a real-estate finance company he ran in California hit the rocksis ironic but history. He says he’s recovered financially, “thank God.” And with that, he takes off his yarmulke, puts on a fedora, and dashes off to an appointment in his BMW.

TAKING WHAT GOD PROMISES

If Jewish theology presents some obstacles for the prosperity gospel, Christian theology presents even more. Like their Jewish counterparts, Christian scholars say it is true that the Bible speaks of material blessings. “This created world is a good world, and the creator wants us to delight in the bounty and beauty of the material world,” says Sider of Evangelicals for Social Action, who received a Master of Divinity degree from Yale University. “Further, God has made us stewards, to create civilizations and to create wealth. And the Bible does say more than once if we live the way the creator tells us we should live that, other things being equal, we will experience material well-being.

“The problem is,” he continues, “the Bible says a whole lot of other things, too.” Every bit as often as it talks about material rewards, he says, “it says that some people are rich because they have oppressed others.” Moreover, Sider says, “there are literally hundreds of Bible verses about God’s special concern for the poor.” So God’s favor doesn’t always seem to lead to riches.

“The meek shall inherit the Earth,” agrees PLU’s Professor Robert Stivers, paraphrasing the famous quote from the New Testament. “You have to give up everything that is a false center.”

While Stivers recognizes that the Bible periodically describes God materially rewarding the faithful, he argues, “You’ve got to look at the main themes of Christianity.” One, he says, is a “heavy suspicion of wealth.” He refers to the often-quoted passage in the Gospel of Matthew, in which a wealthy man asks Jesus how he can obtain eternal life. Jesus tells him to sell his possessions and give to the poor, whereupon he issues the immortal words, “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” There is some debate about whether the “eye of a needle” refers to an ancient gate in Jerusalem, which camels could get through only by kneeling down and being stripped of their baggage, or whether it is a literal image. In either case, wealth is portrayed as an obstacle to salvation, and the sentiment has led as far as asceticism in some strains of Christianity.

“Be careful, you’re quoting scriptures that you don’t finish,” Pastor Treat tells me by phone when I ask him about that passage. He refers to the Gospel of Mark’s version of events. As in Matthew’s version, after the rich man walks away deflated, Peter turns to Jesus and says, essentially, what about us? We’ve given away everything to follow you. Jesus then declares that the faithful will be rewarded “in this age” with 100 times or “fold” what they have given up. (Matthew, in contrast, talks about a reward in “the world to come.”)

Treat continues: “So the end of the story is, if the rich man would have followed Jesus, he would have received 100 fold. . . . So that story is exactly the point we’re talking about now. Jesus is teaching the rich man: If you think your money is going to make your life good or successful, you’re wrong. But if you’re generous with money, it can be a blessing, and it can add to your life.

“I don’t think you should prosper so you can have more and more stuff. I think you should give.” For example, Treat says, “Last year, we took over 10 tons of foodthat’s over 20,000 poundsto the Federal Way food bank. Now the only reason that our church could give is because we had more food than we needed to eat.”

IT’S TEMPTING to view this rationale for wealth-promotion cynically. It’s hard to believe that self-interested concerns don’t account, at least in part, for the popularity of Treat’s prosperity message. He has a weekly show on KTWB-TV, he just took over another church in Everett, and his SeaTac center, which draws about 5,000 worshipers, boasts a K-12 school and a Bible school for adults.

But it’s hard to feel too cynical when talking to some of Treat’s followers. They aren’t avaricious sleazeballs trying to excuse their behavior with religious pabulum. They’re ordinary folks, trying to get ahead and looking for a Christian context in which to do it. “Some preachers will tell you that the world is evil and all that comes from it,” says parishioner Aidan Amaechi, a Nigerian immigrant. “You kind of wonder, should I even watch TV? Should I invest in the stock market?” An accountant with his own firm, Amaechi says Treat’s prosperity teachings offer “an assurance that I’m doing what is right in my own world, in the business world. . . . You don’t have to feel guilty taking what God has promised you.”

You can read this as justification. “It’s a marvelous way to simply enable materialistic people who also claim to be Christians to feel fine about themselves,” says Sider of Evangelicals for Christian Action. Or you can read it as an attempt to reconcile faith with the world most of us live in. PLU professor Killen says she suspects that many of the people drawn to the prosperity gospel see it “as a sign of hopehope that there’s a place for them, hope that they’ll be able to provide for their family.”

Several of Treat’s parishioners are strikingly generous, like Jeff Green, a founding member of Treat’s “Kingdom Builders,” a group that meets once a month after Sunday services to swap business advice. The 42-year-old runs a family business selling meat and seafood at a couple of markets in South King County. Blond and boyish, he radiates sincerity. He says he sees himself as finding “the provision for the vision,” meaning the finances that allow the church to do its work. He contributes 10 percent of his income. And he says he looks for ways to help people not in church as well. One time he gave a friend the down payment on his housenot as a loan, as a gift. “We do it and we forget all about it,” he says of the help his family gives. “We do it for the joy of it.”

“To me it’s like a law of gravity,” says Green’s friend and fellow parishioner, Dan Wingard, a real-estate broker who also tithes. “The more you give, the more you receive.”

Wingard unwittingly raises a question: Do some people give because they believe it will lead to prosperity? Not exclusively for that reason, of course, and perhaps not expecting direct business results in the way that Lapin suggests, but because they believe it is part of the package that leads to God’s favor. J. Lee Grady, editor of the national evangelical magazine Charisma, affirms that one reason the prosperity gospel is controversial is because its slimiest preachers frequently encourage followers to “give, give, giveand it usually means give to me.” The hook, he says, is that God comes off like a “slot machine. If you give enough in offering, then you might strike the jackpot.”

Maybe it doesn’t matter, as long as people aren’t getting swindled out of money they need. As Lapin recalls, an old Jewish saying holds that you should do the right thing for the wrong reason, because later you’ll do it for the right one. The link between giving and prosperity does help explain, however, why churches are increasingly moving into the arena of financial education.

THE BEAST OF GREED

It is June, and a planning session for next spring’s financial-literacy conference is under way in the sprawling suburban complex constituting Overlake Christian Church. On a stage decorated with gift-wrapped packages, motivational speaker and writer Mary Hunt remarks, “I’ve been getting a lot of calls from churches on the subject of giving and how important that is.” She means how important that is for one’s financial health. Hunt’s inspiring story, which launched her current career, is that she climbed her way out of devastating debt in part through a commitment to charity. “I tell people that we gave and saved our way out of debt,” says the ardent Californian. “Giving brought the same kind of rush that spending money had.”

You can understand why churches might be eager to have parishioners hear her message. Church donations are way down, according to others who have come here today. As a pamphlet for participants describes it, the impetus is a “national emergency” fueled by the tough economic climate and manifest in chronic money problems among the populace that threatens core institutions like churches. “It can cost your church or ministry in the form of declining membership, decreasing gifts, forced cutbacks in program and staff, reduced outreach, and uncertain funding for mission projects,” reads the pamphlet.

Speaker after speaker at the planning forum drives home the point that the purpose of this financial literacy work is not riches for its own sake. “We want to help you have more so you can give more,” says Mark Biller, an editor for a Christian financial newsletter called Sound Mind Investing. There’s another motivating factor for churches, tooone familiar to anyone who has seen the way missionaries operate in Third World countries. “See, money’s just the hook to get to their life,” says Bragonier of Barnabas, the organization that conducts financial seminars for churches. “I wait for them to say, ‘Why are you doing this for me?’ That’s the time that I can say, ‘Let me tell you about the savior.'”

None of this means that the desire to help people get control of their finances isn’t genuine. Meeting for coffee one day at a Bellevue Starbucks, Bragonier arrives directly from the home of an elderly, bedridden woman with multiple sclerosis whom he visits every so often to balance her checkbook. Not in performance mode now and looking relaxed in a print shirt and slacks, Bragonier explains how he used to work for a consumer finance company as the head of marketing for eight states. As his Christianity deepened, he began to want to do something about all the consumer debt he saw around him and the havoc it created in people’s lives. That’s when he heard that a group of people was forming Barnabas to teach the principles of a pioneering figure in the Christian finance movement, Larry Burkett. A longtime resident of Bellevue who recently moved to California, Bragonier has led the 19-year-old Barnabas group to become the dominant teacher of Burkett curricula on the West Coast.

A large part of the curricula concerns the evils of debt, which is seen not only as bad financial management but as an impediment to spirituality. If people are consumed with worry about how they’re going to pay off staggering credit card balances, the logic goes, they can’t concentrate on what really matters. “People are in servitude, they’re in bondage to debt,” Bragonier says. “Christians should only be in servitude to Christ.” And so he exhorts Christians to beat back the beast of greed for things they can’t afford.

An even more important principle, Bragonier says, is the distinction between ownership and stewardship. It’s the latter concept that should govern our relationship with money, he maintains. “It’s not our money, it’s God’s money.” The implication is that we should be responsible with it and, again, give rather than hoard our profits.

IT’S NOTEWORTHY that Bragonier operates in a sphere that places the responsibility for people’s financial state squarely on the individual. This is a particular Christian response to economic hardships, whereas other Christians read in the Bible a mandate for social welfare and economic reforms. To Bragonier, giving does not mean handouts. He believes God’s design for welfare can be found in the Bible, which has rich farmers leaving the outside edges of their crops to be gleaned by the poor, thereby enabling them to work for their food.

Bragonier’s teaching of frugality and humility strikes a different note than either Treat or Lapin, though, a harder one to listen to. It’s the flip side of the same coin, perhaps, but it leads to different places. Bellevue financial planner Gary Koontz, for example, says that attending a Bragonier seminar many years ago changed his life. Before, he was simply trying to sell a product. Now he carefully considers whether a client can really afford it.

He’s struck by how many people come to him thinking they don’t have enough money to retire, when in fact they have plenty. “It never seems to be enough. I say, ‘Why don’t you take a trip, see your daughter in Georgia?'” He encourages people not so much to make money, but to spend it. His overarching advice: “There are a lot of things in life more important than accumulating wealth.”