You are excused for thinking that Seattle was on the verge of another WTO meltdown last week. Local media went out of their way to portray animal-rights advocates as extremists who would use violence to disrupt a conference of the American Association of Laboratory Animal Science (AALAS) at the Washington Convention and Trade Center. Not only did nothing happen, reporters missed a tectonic shift in the never-ending conflict between researchers and activists over the use of animals in biomedical research.

It’s a debate that’s always framed in absolutes. Researchers insist that animal research is the crucial test bed for advancing human health. Animal-rights advocates shout that such research is not applicable to humankind and smacks of slavery, and worse. No wonder, then, that the shouting on both sides of the argument stopped when a senior National Institutes of Health official said that one day there might be a ban on the use of chimpanzees in research in the U.S.

Thousands of animal researchers and technicians, as well as federal agencies that fund their work and exhibitors showing off the latest in cages and anesthesia systems, had gathered for the annual symposium. During a session on Oct. 14 on the use of chimpanzees in biomedical research, Kathleen Conlee, a primate specialist with the Humane Society of the United States, asked John Strandberg, the NIH official, about the likelihood of a future ban on experimenting on chimps. Strandberg, director of comparative medicine for NIH’s National Center for Research Resources, effectively guides NIH policy on what animals are used in research. NCRR, among other things, funds America’s eight national primate centers (including the one at the University of Washington in Seattle), two of which use chimps, and a few other chimp facilities around the country.

“It wouldn’t surprise me,” Strandberg carefully replied, “that at some time in the futureI don’t want to get into whenthat chimpanzees are not used” in biomedical research.

No matter how considered his language, Strandberg’s comment represented a global shift. In a later interview, Strandberg explained that the recent bans on chimp research by European Union countries and New Zealand, coupled with pro-chimp public sentiment in this country and intense congressional pressure from U.S. Rep. Robert Greenwood, R-Pa., had nudged NIH’s thinking away from its usual absolutist line: that all animal species should be available for research. “The public perception of this is evolving,” Strandberg said.

THE BAN, if enacted, would be the first time the federal government stopped the use of any species in biomedical research, according to officials at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which regulates the use of animals in research, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, which regulates endangered species and research on wildlife. “This is definitely a first, and it is significant in that respect,” says Peter Singer, a bioethicist at Princeton University and author of Animal Liberation, a book credited by many as launching the modern animal-rights movement in the U.S. “I think what it signals is that there are changes of the sort that people in the animal-rights movement have been talking about for 30 years,” Singer says. “It’s not going to be an all or nothing thing. It’s a matter of making steady progress in changing peoples views.”

Animal-rights advocates contacted by Seattle Weekly say they have never heard such talk out of NIHthat the government would actually consider banning the use of any animal in research.

Researchers were less willing to talk about the issue. Suzette Tardif, associate director of the Southwest National Primate Research Center in San Antonio, Texas, declined to comment on Strandberg’s statement itself. Her center uses chimpanzees in research. Asked what effect a ban would have, Tardif said that chimps are the only species, aside from humans, that contracts Hepatitis C, the leading reason for liver transplants in the U.S.

TRUE, CHIMPS SHARE upwards of 99 percent of human DNA, making them our biological next of kin. In the wild, they make tools and occasionally engage in human-like violence, as opposed to huntingthe only animal species known to do so. They can learn sign language. They are complex, social animals. They create communities and politics within those communities. In effect, they are us and we are them in a way that rats and mice, which animal-rights absolutists insist be freed, probably never will be in the public mind.

Although the research community has decreased its use of chimps in recent years, an estimated 1,325 remain in the NIH research system, according to Strandberg. (None of them are at UW’s Washington National Primate Research Center.)

Research advocacy groups often cite polls showing that Americans favor the use of animals in biomedical research. But last year, a Zogby poll found that a majority of Americans believe that chimpanzees deserve rights equal to those of young children, presumably including the right not to have research performed on them without their informed consent. Clearly, the public at large sees the animal-research issue in far more conflicted terms than do the warring parties.

Some researchers do, too. Says Ajit Varki, a professor of medicine who uses chimps in his research at the University of California at San Diego: “There is a middle path that would be best for all concerned. Change the rules to accommodate our latest appreciation of the ethical status of great apesencouraging excellent medical care for them, from which we can learn a lot, as we do from human patients, and allowing research of the kind that would be generally acceptable in humans.”

As battle-ready and absolutist in their arguments as the researchers and protesters seemed before the conference, the media setup for the conference was ugly and unfair. On Oct. 5, The Seattle Times ran an op-ed piece by UW’s Cynthia Pekow, who serves as the AALAS president, headlined, “Standing up to animal terrorists.” Of course, there are animal-rights extremists who have engaged in arson, property damage, and harassment of researchers and businesses connected with researchers over the past 20 years. Such acts typically have been the work either of the underground Animal Liberation Front or, more recently, the Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) campaign. SHAC’s efforts have mostly been focused on other parts of the country.

What Pekow did was lump the extremists of the animal-rights movement in with what she called “locally based animal-rights groups.” That’s a clear reference to the Northwest Animal Rights Network (NARN). For two decades, the group has been a constant in Seattle, whether protesting fur coats in front of Nordstrom or picketing at UW researchers’ homes, performed with nary a hint of violence or terrorism.

Three days later, Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist Susan Paynter ignorantly predicted that the animal-rights crowd would throw objects”a drink, or something less pleasant”at researchers during the conference, and that those protesters would be from the universe of animal-rights extremists. According to NARN, which was the only group organizing protests during the conference, Paynter never contacted them. Local TV newscasts quickly framed the issue as Mayhem in Our Streets. Even Susan Adler, executive director of the Northwest Association for Biomedical Research and a long-time opponent of animal-rights activists, said Seattle’s media had lost their compass and were ignoring the science that researchers were discussing at the conference.

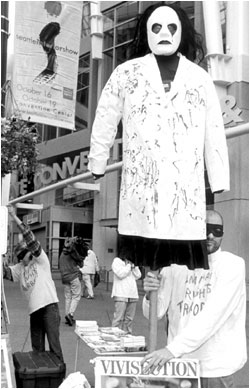

THERE WERE NO acts of terrorism. Andrew Knight, a veterinarian who recently took over as the effective day-to-day head of NARN, led 11 protesters in a “home demo” in front of the Northeast Seattle home of UW AIDS researcher Charles Alpers, who uses monkeys in his work. They stood in the cold on the sidewalk and held signs. Through a bullhorn, Knight announced to neighbors that after at least 15 years of using monkeys, chimpanzees, and mice in pursuit of a vaccine to prevent HIV, science had come up largely empty. That’s further proof, Knight said, of the false promise of the animal model.

At the Convention Center, upward of 30 Seattle police officers kept a watchful eye on protesters, who numbered 17 at the most. Cameras from all four Seattle news stations were there, eager to capture the clash of absolutes. Instead, NARN turned the media circus to its comic advantage. On Oct. 12, the demonstrators stood before the Convention Center wearing hand-lettered T-shirts reading, “Animal rights terrorist, arrest me!” complete with a smiley face. They also wore Zorro masks, purchased from a toy store. Not everyone got the joke. During its 11 p.m. newscast that night, a KIRO-TV anchor, in recapping the day’s events, said in a concerned, parental tone, “Some wore masks,” as if the demonstrators were a collection of window-smashing anarchists.