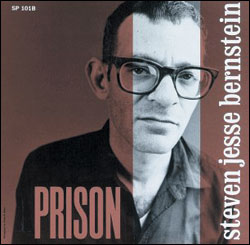

Though I’m a habitual list-maker, I never even thought of trying to count down the top five records to come out of Seattle until I heard Steven Jesse Bernstein’s Prison and immediately decided it was one of the best this town has ever made. Released on Sub Pop in April of 1992, Prison, the poet’s only proper album, simply arrests you. Scored by notable composer, experimenter, and producer Steve Fisk, Prison matches Bernstein’s acerbic, razor-sharp cadence with gorgeous and illustrative jazz, hip-hop, and rock-based sonic fixations. But what makes Prison especially poignant is that the majority of it was completed after the poet died. What will make the EMP exhibit especially poignant is that Fisk will perform a skewed sonic retreatment of the record at the exhibit’s opening night party (6-9 p.m. Friday, Oct. 10).

Upon meeting me in the back room of Second Avenue Pizza, Steve Fisk, the guy who recorded all those weird Screaming Trees records and had a couple of his own rather strange releases out on highly esteemed punk labels like SST, begins with a blunt disclaimer about Bernstein: “He was a really sweet, sweet guy. But we weren’t really good friends.”

He doesn’t mean to disassociate himself from Bernstein, just to clarify their relationship. “I was Bruce’s buddy,” he says, referring to the founding father of Sub Pop, Mr. Pavitt. “Bruce hired [me] to make his record sexy when it wasn’t sexy.”

And Fisk got the job done. Insofar as synchronous trip-rock and spoken-word song/stories about demonic, drug- addled societal misery can be sexy, Prison is the most beautiful hard-core porno flick you’ve never seen. But it didn’t start out that way.

In the late ’80s, around the time William Burroughs was collaborating with people like Sonic Youth and ex-Velvet John Cale, Pavitt, Jon Poneman, and others at Sub Pop thought it’d be cool to record Bernstein in the style of Johnny Cash’s At Folsom Prison. So they recorded Bernstein spewing his modern-day Beat poet songs for a bunch of convicts at Monroe, only it didn’t really work. The performance and recording were done fairly early in the morning and the prisoners, though by all accounts quite taken with Bernstein’s recitations, were quiet and reserved. The recording lacked the raucous audience participation that makes At Folsom Prison so captivating and real. But the dream lingeredit just needed some rethinking. Eventually Sub Pop put the two accomplished eccentricsFisk and Bernsteintogether.

“The idea was to take fixed material and score to it,” explains Fisk. “The thing was, [Bernstein’s] got such a wonderful voice that if you wanted to do what everyone does with Burroughstake four measures and cut it to a hip-hop loopwell, Jesse’s telling stories.”

And Fisk, whose history also includes Ellensburg’s underground literary scene, was committed to keeping the stories intact. He was given cassettes of some spoken song-stories that Bernstein had self-recorded and he started doing what he does best: slinging samples and composing offbeat scores. And then, after only one track had been completed, something awful but not entirely surprising happened. On Oct. 22, 1991, Bernstein killed himself.

A few months later, Fisk went back to work. “I finished it because I knew it was going to be good and I knew it was going to be strong,” he says, “and I knew the context was going to be unbearably sad.”

The two had finished working on “No No Man (Part One),” a song that Soundgarden would later frequently use as intro music for their live shows, and Fisk had played Bernstein early versions of the definitive track “More Noise Please” and the poet fully endorsed the composer’s pulsing, shimmering, stomping sonic accompaniment. In fact, Bernstein had given Fisk “complete permission” to do exactly what he wanted with all the tracks.

Not that he always wanted to do a lot. “With a piece like ‘Face,'” Fisk explains, referring to Prison‘s longest track, a 12-minute discourse that brutally defines Bernstein’s tormented, illness-ridden youth, “you want to stay out of the way.”

“Face” begins with the poet stoically and sarcastically stating, “The following is pure fiction. Actually I have been handsome and popular all my life,” and then goes on to proclaim, “There has always been something wrong with my face.” No music is heard for the first minute and a half of Bernstein’s narrative, and then a building buzz begins. A whirling, squishy hum accompanies the poet as he dryly explains how, as a boy, he wanted to cut off one of his ears but ended up with only a pathetic dribble of blood. True to Fisk’s guiding inclinations, “Face” is one of the album’s least musical tracks.

And yet, Fisk explains, “there’s more hokum in ‘Face,’ actually, than on any other tracks. There are two places where he’s surrounded by his peers and they’re ganging up on him, one [of the background sounds] is lions slowed down and the other is bees slowed down. It’s subtle, it’s very, very quiet, but the ambience gets bigger and creepier.”

BACK WHEN I first heard Prison, I had guessed that Fisk must have had to make extensive notes or perhaps even build a complete map with graphic relief in order to guide himself through the pained sea bottoms and hilarious, sarcastic, jesting mountain peaks of Bernstein’s vocal work. But he says that wasn’t the case at all.

“No, I just lucked out,” he insists. “Seriously, it was like rowing two boats down a river and hoping they could stay in synch with each other. And it was easy to do. The actual finding of [sounds] to work with the text was simple. He’s just musical all the time. When it’s off and it still works, that’s because he’s like a singer.” Fisk completed the record with his “arthritic little sampler” and a few other toys, and after a few more weeks of mixing and mastering with Stuart Hallerman, Prison was released in April ’92.

With his jaundiced deadpan, Fisk recalls the atmosphere in Seattle at that time. Here he was, about to see the release of some really heavy shit that had, just nine months prior, become even heavierand Belltown, where he was living at the time, was an idiot’s zoo.

“That time in the early ’90s was like some horrible collage of Silver Lake and Green Acres,” reminds Fisk. “Your best friend is having lunch with the heavy metal band who came to have lunch with Kenny Laguna because Kenny Laguna is working with Bikini Kill. You couldn’t walk out your door without seeing Tabitha Soren or AT&T using the Cyclops as a backdrop for young people drinking malts while talking on their cell phones. There are good things about having people move to Seattle, but there’s dumb shit, too. It was so fucking Green Acres. Anyone with a tap dance or a folk band or a juggling routine was going to have their five minutes and if they couldn’t get real MTV, they’d get French MTV. It was disgusting.”

And on his own begrudged corner of the meat market, Fiskwho, it should be noted, moved to Seattle after doing a bunch of cool stuff like recording the

first Beat Happening records and working with bands who had yet to be labeled with the dreaded G wordsays that by the time the record was complete, he couldn’t go anywhere without people asking him about it. By April of ’92, those people could hear it for themselves.

Bernstein has been gone for a little over 12 years now, and EMP’s multifaceted portrait of him is a long overdue. And maybe, considering the venue, even a little strange.

“Yeah, Jesse would say something very poetic about what a rich man does with his money,” says Fisk. “A museum about rock? He would have thought that was the funniest thing in the world. A part of him would’ve loved that he was a figure there and that people would show up, but I think he woulda pulled a bomb threat.”

Fake bomb threats, random knife pulling, and targetless bottle chuckings were part of the Bernstein persona, and while that chaotic anarchy had its bizarre charms, hopefully there won’t be any hazards getting in the way of Fisk’s aural rearrangments of Prison at the opening event.

FOR FRIDAY NIGHT, Fisk says, “I’ve made a little series of atmospheric vignettes that are from micro-portions of the Prison readings, and I set them up to go for long periods of time and turn into different things. I’m doing this in a quadraphonic environment, which is actually a ’70s thing, No one does quad anymore but the Experience Music Project is setting up a system for me. I’ll be set up in front of that guitar sculpture. Anyone who’s ever seen my live set knows it’s not very theatrical. I’m going to be holding keys down and turning knobs. This is not about me being clever or entertaining.”

Luckily, Fisk, who in 1980 opened for angular post-punk legends Gang of Four with a tape deck and a friend and was booed off the stage, is no stranger to other people’s aversionsand you get the idea that he couldn’t care less.

“I’m supposed to be pumped into the upstairs party room, and I’m sure they’ll turn it off. What I want to do is create a sonic environment that’s about his voice, it’s, like, incessant repetition, and I’m sure it’ll bug some people,” he says.

Which is of course, completely in keeping with the spirit of Steven Jesse Bernstein.

I bet he and Fisk would have grown to be great friends.