THEY MAKE THEIR way not armed with bombs or verses from the Koran (though they do stop occasionally to pray), but bearing only the simple hope for a better life. Is that such an unreasonable objective? Is that such a threat? To view Michael Winterbottom’s bleakly pessimistic film In This World (which opens Friday, Sept. 19, at the Uptown), the answer is “Yes.” The West doesn’t want such illegal immigrantsnot as busboys in Paris restaurants or vendors on the streets of Prague. Nor does it want to shell out the expensive foreign aid required for law, order, sanitation, and fundamentalist-averse education in their homelands. As Dubya is belatedly admitting, that costs a lot of money.

World isn’t a political film that makes such explicit political points, but they come inevitably to mind as Fortress Europe and our own Department of Homeland Security are confronted with the ceaseless tide of Third World want and desperation. Winterbottom is fundamentally a humanist filmmaker who wants to humanize the headlines of Mediterranean drownings and asphyxiated Chinese stowaways that jaded Westerners ordinarily flip past to reach the stock tables and sports pages.

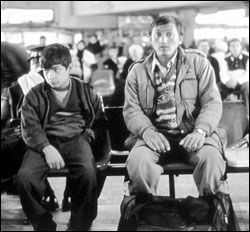

This rather clunky docudrama follows solemn Enayat and his younger, jokester orphan cousin, Jamal, on their four-month westward journey from Pakistan. Sent by their family to earn and learn in London, money stashed in the liners of their tattered shoes, preyed upon by smugglers on every stop of their overland passage, they have a kind of quiet, heroic perseverance. Winterbottom is as sympathetic to these refugees as he was to the Bosnian orphans of Welcome to Sarajevo, and World‘s stir-your-conscience tone is furthered by periodic, disruptive voice-overs, maps, and graphicslike bulletins from a hectoring BBC special. The punctured plot, such as it is, is that of a road movie: Get from point A to point B, whatever the cost.

Jamal and Enayat do reach the West, but at a profound cost. In World‘s most brutal sequence, the two are locked inside a pitch-black cargo container aboard a ship crossing the Adriatic. The entire movie is shot in DV and handheld, using only available light, and here the v鲩t頰roduction values make for scenes that are like The Blair Witch Project in Pashto: You can’t see anything, can’t hear anything but the moans and groans of terror. Even in its more benign moments, as the boys ride in the backs of Toyota pickups plying ancient caravan routes, you feel the jarring springs and taste the yellow dust. World is a travelogue without pleasure, a trip no tourist would willingly endure, like an issue of National Geographic that burns your fingers and eyes.

WORLD CERTAINLY succeeds in rousing pity and alarm; but like a CARE commercial or a Bush speech, the effect only goes so far. A real documentary might have been better able to address the bigger questions in Jamal and Enayat’s journey: Would the West’s freely accepting these immigrants do anything to rectify the disparity between the two cultures? How much would the modernized West be willing to spend to bring the Third Worldcurrently akin to medieval Europe, except with AK-47s, explosives, and flight-instruction manualsinto at least the 19th century? I don’t have the answers, nor does World offer anywhich speaks to its narrative limitations. The story is often dramatic but also tedious, like the voyage itself, I suppose.

As Jamal and Enayat are variously packed between boxes, oranges, and sheep, they literally become cargo: products of a polarized system of economicsnot of religion, politics, or culturein which supply and demand are forever imbalanced. Meaning that no matter how many fences we build, no matter how many port inspectors we hire, all roads lead here.