BOB DYLAN

BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 5: THE ROLLING THUNDER REVUE

(Columbia/Legacy)

In a dark period of five hundred years Rome was perpetually afflicted by the sanguinary quarrels of the nobles and the people. . . . When every quarrel was decided by the sword, and none could trust their lives or properties to the impotence of law, the powerful citizens were armed for safety, or offense, against the domestic enemies whom they feared or hated.

—Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

In retrospect, one can hear it in Dylan and The Band’s 1974 shows, documented on the double album Before the Flood—a tension just beneath the surface, a sense that the fuse is smoldering, on songs like “It’s All Right Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” and “Gates of Eden.” “Even the president of the United States/Sometimes must have to stand naked,” Dylan sang, and the place went nuts. Those words were, after all, a lot more loaded in ’74 than they had been in ’65.

Dylan had been through some changes by that time. He hadn’t played in public for six years following his motorcycle accident and hadn’t been on the road as an extended commitment for closer to eight. During his time away from touring, he’d released albums like Nashville Skyline and John Wesley Harding, the former a country-shuffle set nobody knew what to do with at the time, and the latter a brooding collection of inscrutable songs that might as easily have been written in 1768 as two centuries later.

The country had been through some changes, too—changes like My Lai, the Tet Offensive, Watergate, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, race riots in Watts, political riots in Chicago, and the shootings at Kent State. Throughout the early ’70s, it seemed as though the state had become more and more efficient, while the protest movement was enduring the slaughter or exile of its most important figures. The America in which Bob Dylan returned to touring was not the one from which he’d receded in 1967.

The tension on the ’74 recordings with The Band seems to emerge from Dylan feeling his way along, testing old songs in a vastly changed context; to complicate matters, The Band’s music had gotten cleaner and more intricate during the same period. As a result, Dylan sounds tightly coiled during his solo numbers, while The Band sound freshly professional and polished in theirs; the collaborative performances come off like an extremely tentative cease-fire. It was a tension Dylan was to resolve—in spades —just a year later.

THE CONCEPT BEHIND the Rolling Thunder Revue was part gypsy caravan, part traveling hootenanny: Collect a bunch of musicians and artists and writers, some of whom are friends and some of whom are random selections, take the whole mess out to the people in the hinterlands, and record what happens

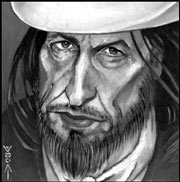

It was the M.O. Dylan had used to assemble Desire, one of his bloodiest and most unique albums in years (he’d literally pulled violinist Scarlet Rivera off a street in New York and directly into the studio); he kept bringing people into the recording sessions, wild aggregates of instruments, until he found the sound he wanted. Immediately, he began conceiving a tour of appropriate size and spectacle.

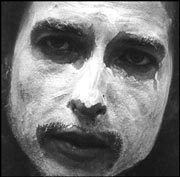

The Rolling Thunder Revue shows were as legendary for their internal drama as they were for the blazing performances they delivered. This was the tour on which (1) Dylan’s marriage to Sara fell apart, (2) Joan Baez finally decided to hell with him, (3) the epic film Renaldo and Clara was assembled, (4) Dylan painted his face white and wouldn’t explain why, (5) writers Allen Ginsberg and Sam Shepard were on board for no reason anyone could name, and (6) the effects of dope, booze, and pills (as documented in Don’t Look Back) could be scientifically contrasted with the growing impact of cocaine among the public in general and within the entertainment industry in specific. The Bootleg Series Vol. 5: The Rolling Thunder Revue captures Dylan’s performances in these high-tension shows perfectly, with a clean sound taken directly from multitrack source tapes that even the best bootlegs have never been able to approach.

Dylan’s songs had never sounded this ferocious—the opening guitar run on “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You” could have been taken from Lou Reed’s contemporary Rock and Roll Animal (and was, in fact, performed by Reed’s axman on that recording, Mick Ronson)—and the man himself had rarely sounded this invested. The music Dylan performed on this tour was, by and large, angry and visceral, and the set list on Rolling Thunder is pitch perfect in this regard.

Desire provided vivid material like “Idiot Wind,” “Hurricane,” and the towering “Isis,” but he also reached back into his catalog nightly, for “Just Like a Woman,” “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”—a song that walked a perfect line between sorrow and blind rage even in its acoustic version, and only sounds more incendiary here.

Throughout the Rolling Thunder tour, Dylan was updating old material and wedding it to the new—drawing the line, in essence, from the frustrated protest of “Blowin’ in the Wind” to the angry prophet of “Hurricane.” The immediacy of that project seemed to fire the performances of the other players, as well; the bonus DVD packaged with initial pressings includes a performance of “Isis” so flatly terrifying that my lady friend backed away from the television as it played. (I poked fun at her, largely to mask my own horror.)

One crucial element of the Rolling Thunder concerts, however, is missing from The Bootleg Series Vol. 5. These were essentially collaborative shows, whose overall structure was important to the artistic vision. Kinky Friedman, Joan Baez, a young T-Bone Burnett, and Bobby Neuwirth all took center stage at various points in the evening; you won’t find those moments here. Also, there was an awareness of American folk music history that’s sorely missed on the official release. You won’t hear Woody Guthrie’s “Plane Wreck at Los Gatos” and “Gotta Travel On”—the traditional show closer that featured rotating lead vocals on each verse—”Railroad Boy,” or Burnett’s own ghostly “Silver Mantis,” unless you score a bootleg of a full performance.

As a document of Bob Dylan’s own mid-1970s cosmic workout, however, The Rolling Thunder Revue is essential. Later explorations would try to achieve the same scope—the underrated Street Legal, for instance—but this was the one moment when the spark caught and held—and then burned down the house.