SINCE ENGLISHMAN Josiah Spode made the first bone china in the 18th century, it’s been known that adding finely ground, calcinated cow bone to clay increases translucence and strength. Charles Krafft has found that human bones work just as well.

“I ball-milled Larry’s dad in this,” says Krafft, standing next to the basement machinery where he ground up the cremated remains of Fred Reid (father of his friend and collaborator Larry Reid). Krafft added the remains to clay and used the mixture to make a full-scale porcelain army helmet to commemorate Reid, a WWII veteran.

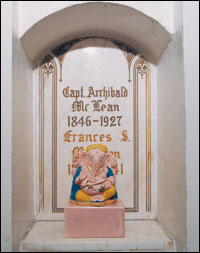

The army helmet is part of Krafft’s line of “Spone” commemorative china (the word is an amalgamation of “Spode” and “bone”) that also includes a bulldog figure made from the remains of veterinarian Dr. Robert Thornberry, an Absolut bottle made for (and from) Krafft’s late friend David McCann, and a figure of the elephant-headed Hindu god Ganesh for the late Seattle photographer Joseph Fitzgerald. The pieces, all of which were commissioned by the friends or families of the deceased, also function as reliquaries for the excess ash not used in their creation.

Krafft has become well known as a provocateur since he started working in ceramics in the early ’90s (before then, he labored for almost two decades as a painter in the Northwest Mystic tradition). His “Disasterware” collectible plates depict not triumphs but tragedies, from the Hindenburg to the Wah Mee massacre, and his “War Museum” series offers true-to-scale porcelain AK-47s, hand grenades, and missiles, all painted in the curlicue patterns of your grandma’s china. No doubt he is gratified when anyone is shocked by his work, but there is in the Spone series something more than sensationalism at work, something wonderful and large-spirited. For all his gruffness and morbid humor, Krafft is seriously devoted to the business of commemoration. The Spone tributes to the departed are no less sincere for being a product of Krafft’s unsentimental, matter-of-fact acceptance of death.

Krafft, who has been on the Seattle scene since the 1970s, famously hates the stuffy atmosphere of art galleries and has not been represented by one since he left Davidson Galleries more than 10 years ago. (He occasionally appears in group shows at the lowbrow Roq la Rue). “Ring of Spone” (the name is derived from Beat poet Lou Welch’s poem “Ring of Bone”) will be on view this weekend in the Queen Anne Columbarium at Mount Pleasant Cemetery on the north end of Queen Anne Hill (520 W. Raye St., 206-282-1270), and will feature a video Krafft shot of funeral pyres in Benares (a Hindu pilgrimage site in India), with live accompaniment on opening night by electronic noise duo the Golden Climax Twins. And no, it’s not a coincidence that opening day is Friday the 13th. (See calendar for details.)

Besides the bulldog, Absolut bottle, and other commissioned pieces, “Ring of Spone” will include eight shovels with porcelain blades made using a stash of anonymous, unclaimed cremated remains that were given to Krafft by a former mortuary worker (and which were otherwise going to be thrown away). The shovels, decorated with pine cones in the same blue-on-white Dutch style of porcelain painting known as delft that Krafft mastered while working on his Disasterware, have obvious associations with death and burial, and will stand like sentries in the eight points of the octagon-shaped columbarium to complete the Spone circle.

SPONE DIFFERS FROM true bone china in that Krafft uses every bit of the remains, not just the bones, allowing the bodies of the departed to express individual quirks. “This is dental bridge particulate,” he says, pointing to a big silver blotch and other blemishes on an alternative version of the Reid army helmet. “And this is some other kind of shit that came out of the bone matter that I can’t control. It’s exuding contaminates.”

To make them even more complex and chunky, some of the pieces have had bits of bone added to their slip (the liquid clay mixture used in the casting process) to give the final product a gravelly texture. Krafft hands me odd bits of dental fillings and bags of ash and bone chunks as he explains all this, and while part of me is going, Holy shit! This is dead people! I feel compelled to adopt his casual attitudean attitude I see as somewhat disingenuous on his part, but only somewhat. Krafft may take an eccentric’s pride in taboo breaking, but he is a craftsman, and intimacy with his materials has been earned over countless hours of labor.

“It’s important to realize that this is not illegal. It’s not even creepy,” says Larry Reid, Krafft’s logistics man and co-author of Charles Krafft’s Villa Delirium (Last Gasp, 2002), a retrospective of Krafft’s ceramic work. A scruffy, smiley guy in a Gas Huffer baseball cap, Reid has an encyclopedic knowledge of contemporary art, ran the “punk rock/dada” gallery Rosco Louie from 1978 to 1982, and was also the director of CoCA back when it was actually interesting to go there. “Who wouldn’t want to be immortalized as a work of art?”

Says Don Thornberry, son of the veterinarian who ended up as a bulldog: “My dad’s ashes were just sitting in a box, and I thought he would approve.” Thornberry knew Krafft slightly in the ’70s when the artist was living in Fishtown, an artists’ colony along the Skagit River. He says Krafft at the time was a “semi-mythical hermit character.” He commissioned the piece after seeing a story in Salon.com that mentioned Krafft’s Spone project. The original bulldog from which the Spone was cast was made by Thornberry’s mother in a hobby class and sat on her husband’s desk for 20 years. “It’s not great art or anything,” says Thornberry of his mother’s original, “it’s really more like something you would find in a gift shop. But it adds another layer of meaning.”

Krafft has been written up in highfalutin Artforum magazine but is more closely associated with the journal of hot rod/tattoo/comic book art, Juxtapoz. Disdainful as he is of fancy art talk (his Tortures and Torments of the Postmodern Masters, painted on a plate, shows a bound man being pecked to death by ducks), Krafft’s latest work is extraordinarily rich in subjects for eggheaded pontification: There’s his recasting (literally) of found images, the undermining of his own creative authority through collaboration with clients, and an expansion of what fine art can be (sculpture, transubstantiation, reliquary, and kitschy appropriation all at once). The stunning thing, though, is the utterly unpretentious way he accomplishes all thishis work is so direct, so clear, so boldly readable, it makes the typical obscurity of most other current art look positively sissified by comparison. Spone, however, is not the result of trying to bring to life some preconceived theory, but of letting the materials themselves act as muse. Krafft speaks about “flowing, snowlike bone matter below the surface of the clay” in a hushed, far-off voice, as if he has been momentarily hypnotized.

After Disasterware, porcelain weapons, and Spone, what’s next? One thing is certain: “Tell the people out there in art land that I don’t want to do their pets!”