BEACHCOMBER

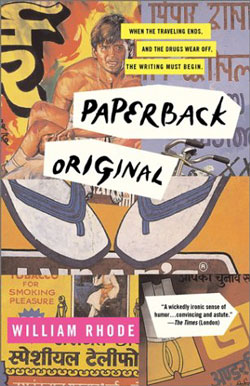

IT SEEMS BOOKS and movies depicting the creative struggles of writing are all the rage these days, from Michael Chabon’s Wonder Boys to Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation. Add to that list Will Rhode’s winking postmodern debut, Paperback Original (Riverhead, $14). The Brit author’s flashy 454-page effort finds protagonist Joshua King attempting to pen the great novel—not for the sake of art, it turns out, but for money. Specifically, the inheritance his late father—victim of a tragic Viagra overdose—wills him on the condition that he write a best seller (with pops as a character) in less than five years’ time. Unfortunately, King isn’t really the type to be bothered with such a mission, holed up as he is in the down-and-out Delhi district, working as a scruffy staff writer for Hindu Week magazine, and immersing himself in a seedy Indian underbelly of drugs, drifters, and down-and-outers.

While Rhode successfully establishes this Brewster’s MillionsmeetsFear and Loathing in Las Vegas scenario, his delivery isn’t as strong as his setup. The book soon suffers from a serious lack of character development. Still, there is a certain louche charm to Rhode’s prose, enough to carry readers to the end of a twisted travelogue that manages to pack in a comely Dutch tourist, a notorious drug lord, and plenty of Bollywood-inspired action along the way.

Although Paperback has been frequently compared to Alex Garland’s The Beach (allegedly for its potential to become a “generation defining” novel), Rhode displays his own unique voice and style. He’s already being pegged the avatar of “backpacking lad lit” for his off-kilter tale—part earnest travelogue, part On the Roadstyle adventure. The book is already a hit in the U.K., and it should attract younger readers on this side of the pond with its hip Anglo sensibility and crafty charm.

Bob Mehr

Will Rhode will read at Elliott Bay Books (101 S. Main St., 206-624-6600), 7:30 p.m. Wed., April 9.

THE DECISIVE MOMENT

“CLARITY IS WHAT he needed. He felt mired,” John Murray writes of one of the characters in his debut short-story collection, A Few Short Notes About Tropical Butterflies (HarperCollins, $24.95). As Murray shifts from first-person to third-person narration in the other seven tales, jumping between protagonists who are men and women, immigrants and WASPs, he keeps returning to that craving for self-definition. In “All the Rivers in the World,” a chubby Maine hardware-store salesman travels to Key West to retrieve his runaway father. There, his dad’s girlfriend says of life, “When you boil it down, it is all about 15 minutes here and 15 minutes there, the moments when you are really tested. . . . Everything else is just biding your time for when you’re needed.”

It sounds a bit like Hemingway—a man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do, in as few terse words as possible—although Murray’s women feel the same need. An Australian who washed up on the shores of the Iowa Writers Workshop (where he now also teaches), Murray makes his stories echo and overlap thematically; they’re full of doctors (his own background), entomologists, dying parents, and adventurers who risk their lives in Third World countries. There’s a certain highIQ, overachiever vibe reminiscent of Andrea Barrett (Servants of the Map), with frequent references to Darwin and natural selection. In other words, we’re all being tested for fitness, biding our time until the big test arrives.

Unlike in Hemingway, however, not everyone gets his elephant. A nurse abandons her colleagues to guerrillas in 1994 Rwanda; a teenager betrays his older brother in 1968 Iowa; both mothers and fathers flee their own families in Murray’s stories, most of which are set in the near past. He gives his characters a certain dated, shopworn stoicism—”Perhaps you have to become nobody to understand who you are”—that might’ve seemed profound to undergraduates in the ’70s. He employs clean, effective prose in the service of characters who, M.D. or no M.D., aren’t always so smart. But they’re still struggling toward their tests, uncertain of the outcomes, and Murray makes you respect that struggle.

Brian Miller

John Murray will read at University Book Store (4326 University Way N.E., 206-634-3400), 7 p.m. Thurs., April 10.

FAST GIRL

AH, THE MODERN coming-of-age memoir and its holy trifecta: crazy and/or abusive parents; wayward teen experimentation; and, of course, credit for time served in parochial school. Kathy Dobie’s The Only Girl in the Car (Dial Press, $23.95) bats a clean two for three (her parents are genuinely loving and generally sane), but it’s her sharp, clean prose that elevates an otherwise familiar story above the self-mythologizing therapy-speak of a thousand similar works.

Growing up in a large, affectionate Catholic family in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Dobie is a typical eager-to-please middle child. But when her teen years hit, so do the hormones; even though she isn’t quite sure what sex is, she knows she wants to have some. More proactive than most 14-year-olds, she decides to put on her halter top and hip huggers and pose herself seductively on the front lawn until somebody stops. The man who does—an oily, nervous 33-year-old named Brian—takes her to the drive-in and promptly separates her from her virginity. That unremarkable experience only feeds her hunger: “Men ushered me into sexuality,” she writes, “but I wanted boys, boys with light in their eyes, hoarse voices, hard arms, silky chests, bodies that were my size. And the boys I wanted were the bad ones—confident, aggressive, dirty-minded ones.”

And bad boys are just what she gets. Easy-cursing, cigarette-smoking Rumblefish delinquents pass her around until one, Jimmy, gets her heart. But he also finally inflicts the most damage—leading to an ugly, devastating turning point for Dobie, until then young and naive enough to believe her brand of sexuality would be the currency of freedom, not self-loathing.

A contributor to Harper’s, The Village Voice, and Salon, Dobie writes about her life without self-pity or excuses. Anyone who’s ever been—or known— a teenage girl will relate completely. And anyone else who’s flung epithets at the school slut or written nasty words on the bathroom wall will be a little wiser for reading this memoir.

Leah Greenblatt

SOB STORY

READING A BOOK is generally a selfish act. One reads to escape, to learn, or to be entertained. Rarely does one read as a courtesy to the author. But Sue Miller’s The Story of My Father: A Memoir (Knopf, $22.50) is a different story, penned as a sort of therapy for its author. Her deliberately cathartic and deeply personal book forces the reader to become a benevolent listener—a semicaptive audience—even if that’s not her intention. At least for this reader, this added responsibility stunts the enjoyment garnered from an otherwise thoughtful, intimate memoir.

Miller portrays her father in life and in the years leading up to his death, when she was his primary caretaker during his descent into Alzheimer’s-induced dementia. The book’s about him, but it’s also very much about her: her relationship with him; her struggle to care for him in his illness; and how the experience has changed her feelings both about her father and her own life.

It’s a difficult, often grueling read, as with any emotionally charged endeavor, but it has its rewards. It’s informative—you may feel guilty when you find yourself most interested in the morbid, scientific sections on Alzheimer’s effect on the brain. It’s touching, too, and Miller’s memory of her scholar-minister father is rendered with love and sensitivity. Still, that feeling of dutiful sympathy can be daunting at times—like listening to your best friend keep mourning the death of her cat years after the fact. Except this isn’t your best friend, and the subject of Miller’s grief is significantly heavier. These 192 pages are beautifully written, but a shorter essay would’ve worked just as well for the reader— although perhaps without being so therapeutic for Miller.

Katie Millbauer

Sue Miller will read at Third Place Books (17171 Bothell Way N.E., 206-366-3333), 7 p.m. Thurs., April 10.