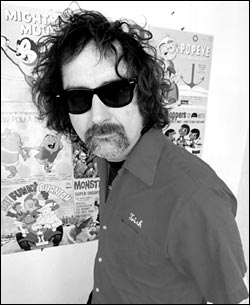

If you could peer behind his pitch black Ray-Bans, you might see Scott McCaughey’s eyes light up. The leader and one constant of the revolving-door collective known as the Minus 5not to mention linchpin of the Young Fresh Fellows, catalyst for Tuatara, and sideman to R.E.M.McCaughey is well-known for his unbridled excitement when it comes to all matters musical. An unapologetic rock geek, he’s the sort of fellow who can plumb the depths of pop arcana and come up wanting more.

So when he’s handed a copy of Would You Believe, a hard-to-find record by little-known late-’60s Britpop auteur Billy Nicholls, his excitement is hardly surprising.

Back in 1968, Nichollsmuch like McCaughey was a well-regarded if under-the-radar figure. Signed to Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham’s Immediate Records label, for his one stab at rock immortality, Nicholls joined forces in the studio with modfathers the Small Facesthen coming off their masterpiece, Ogden’s Gone Nut Flake, and at the height of their powers. Together with them and a handful of other like-minded compatriots, Nicholls fashioned what some consider the era’s great “lost” album, a British equivalent to the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds.

As McCaughey continues looking over the disc, it’s not much of a stretch to find a certain cosmic symmetry, a near-perfect parallel between the Nicholls/Small Faces team-up and his own recent collaboration with Chicago “it” band Wilco. The result of that union, the just-released Down With Wilco, may not have achieved cult classic status just yet, but one pass though its 13 songsa quirky collection of deft, melodic laments and snappily written candy flossmakes you believe it might be well be on its way.

And if you look again, closely, the gleam in McCaughey’s eyes probably has less to do with the CD in his hands than the thought that somedayperhaps 35 years from nowmusic fans might be passing one of his records between themselves with the same sort of glee.

The idea for a Scott McCaughey/Wilco pairing had been incubating since 1999. “[Wilco frontman] Jeff [Tweedy] and I banged a few songs together when they were on tour opening some shows with R.E.M,” says McCaughey. “Then I played a gig in [Chicago], with them backing me as the Minus 5that got us really going, too. But it was so hard to get a chance to [make an album] because of their schedule. Then, all of a sudden, when the release of their last record got delayed, they had some time, so we just rushed to do it.”

With Wilco fresh off recording their own meisterwork, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, the group joined McCaughey at Chicago’s SOMA studios for two sets of rapid-fire sessions in the fall of 2001.

McCaughey brought a wide mix of material to the studiosome songs had been written just weeks before, while others included bits and pieces that dated back decades (“There’s a chorus in one,” notes McCaughey, “that I’ve had kicking around since 1978”).

Historically, McCaughey’s m鴩er has been decidedly tongue-in-cheek, and while Down With Wilco does revel in its fair share of blithe moments, there’s an undeniably elegiac quality to the bulk of the record. Certainly, it’s hard to recall anything as mournful as the album’s valedictory, “Dear Employer,” in his catalog. It’s a conscious shift that McCaughey credits Tweedy for helping bring about.

“Jeff definitely seemed to have a vision for what kind of a record it should be. He could feel which songs would hold together best. And I played him a lot of stuffprobably 25 different things. And most of the things we left off or didn’t do were the more rocking songs.” (Much of that uptempo material appears on the limited edition Minus 5 disc, In Rock, while a handful of others may turn up on an M5/Wilco EP later this year.)

As the two sides settled into the confines of SOMA, a strange alchemy began to take place, a charmed collision of McCaughey’s grinning left-field compositions and Wilco’s audacious arrangements. The groupTweedy, drummer Glen Kotchke, and multi-instrumentalists John Stirrat and Leroy Bachset to work on the songs, mutating tempos, switching styles, shifting and changing things until the best approach finally revealed itself.

“They’re no strangers to trying things a number of different ways,” observes McCaughey, and the band proves it convincingly, taking a song like the “The Old Plantation”which began as simple two-chord dirgeand unexpectedly turning it into a soulful Al Green pastiche. “Unfortunately, we didn’t get Al Green to sing it,” jokes McCaughey, “but it came out pretty cool, regardless.”

Musically, much of the album draws from Wilco’s recent playbook. “Where Will You Go” finds the group mining Steely Dan territorythe drawling, jazzy riff and insistent marimba hook unfolding like an outtake from Aja. Elsewhere, the moody, dissonant swirl of opener “The Days of Wine and Booze” and the minimalist bass ‘n’ drum exercise “Life Left Him Here” are set firmly in the avant-pop direction the band has been forging of late.

Perhaps the group’s influence can be felt most in McCaughey’s singing, as Tweedy encouraged him to keep as many rough and first-take vocals as possible. “He didn’t want me to redo them, or make them too perfect . . . not that my vocals could ever be perfect, by any means,” laughs McCaughey. While he’s sometimes been derided for his reedy midrange, there is a casual, almost offhand warmth to McCaughey’s voice herebest characterized as Apples in Stereo’s Robert Schneider doing a George Harrison impression.

Predictably, familiar figures crop up all over Down With Wilcofrom the Beach Boys (“That’s Not the Way It’s Done”) to the Beatles (“View From Below”). Yet other cuts resemble nothing so precisely; “The Town That Lost Its Groove Supply” a loopy, kiddie-song noveltymay only have its antecedent among Nilsson’s more skewed renderings.

“Like a lot of stuff on this record, we couldn’t figure out what that sounded like when we were done,” chuckles McCaughey, “but we loved it anyway.”

After completing tracking in Chicago, McCaughey brought the tapes home to Seattle. Sitting with the songs for a month or so, he then enlisted longtime Minus 5 conspirators Peter Buck and Ken Stringfellow for a series of hit-and-run overdubs, their final touches turning the already ambitious sonic scope of the album into a full-on kitchen-sink affair.

“We did it all so fast,” says McCaughey. “Ken came over to my house two afternoons for, like, three or four hours. He hadn’t heard the songs at all.”

The fingerprints of the Posies player are evinced in an array of plangent organ fills, and his angelic croon crops up at various points, notably on the catchy answering line of “I’m Not Bitter” Stringfellow and McCaughey bringing it on home with an Anglo-pop take on the old Sam Cooke/Lou Rawls gospel call and response.

Meanwhile, R.E.M.’s Buckwho also recorded his parts in similarly quick fashioncomes up with a series of small yet typically tasteful contributions: the 12-string Merseybeat lick that crops up in “Life Left Him There”; the fleeting snatches of mandolin on “Retrieval of You.”

“He’s amazing at banging stuff out like that,” enthuses McCaughey. “As Robyn Hitchcock often says, he likes the way Peter plays a song the first time when he’s never heard it before. Peter is so good at instantly tuning into a song, that the first thing he does is usually really, really great.”

(If Stringfellow and Buck had a tough task approaching the songs cold, violinist/ cellist Jessy Greene was truly flying blind; she was only given song titles and keys to play in and forced to improvise. It’s her odd, discarnate voice that counts off several tracks.)

Ultimately, the small army of instru-ments and overlapping soundsfrom Moog to mellotron to Moroccan horncreate a kind of mosaic effect, the sort of aural artwork that can be appreciated for both its intricate detail and big-picture beauty.

If a seat-of-the-pants aesthetic guided the recording, a more measured and utilitarian approach was taken for the album’s postproduction. “It’s funny, every part of this record was made under superweird situations, especially the mix,” McCaughey says. “I was in London to testify in Peter [Buck’s] air-rage trial; I’d already gone there once to testify, and they threw the first jury out. And I’d been so stressed waiting that I couldn’t sleep. So when I went back the second time, I thought, ‘I’m gonna freak out unless I’m working every second.'”

Using the decidedly unusual downtime to work on the mix with English engineer Charlie Francis (High Llamas, Ultravox) at London’s Studio 86, the pair somehow managed to merge the myriad elements into a single, seamless stretch of sound.

Of course, even during these final moments, the ever-enterprising McCaughey sought some additional layers of noise, enlisting High Llamas headman Sean O’Hagen to bring some twisted banjo to the proceedings.

“Yeah, that was pretty last minute,” admits McCaughey, laughing at his own well-intentioned excess. “My whole thing with the Minus 5 is to go with whatever opportunities, coincidences, and disasters come along. That’s just the way it happens with this band . . . it’s the way it always should be.”

At the time, McCaughey’s decision to title the album Down With Wilco was intended as a show of solidarity with the group, which had endured a much publicized battle with Warner Bros. Little could he have guessed that he was soon to find himself in similar record company limbo, as the Disney-owned Mammoth Records imprint the Minus 5 signed to ceased operations abruptly last spring.

Minus 5: McCaughey (center) flanked by (from left) Rieflin, Ramberg, Stringfellow, and Buck.

photo: Bootsy Holler |

“The record was supposed to come out last June, but as [Tweedy] said, it’s the ‘curse of Wilco’which I don’t really believe,” says McCaughey. “When the plug got pulled on Mammoth, [Disney subsidiary] Hollywood Records had the option of putting the album out, which they didn’t. But luckily, they were cool about helping me get it back. They could’ve hung me out to dry.”

With the rights to the album secured, McCaughey was eagerly courted by a half-dozen indie imprints, eventually signing with Southern roots-pop label Yep Rocchiefly, he confesses, because the company’s roster included one of his heroes, Nick Lowewhich finally released the album last week.

While the Minus 5the live version of the band features McCaughey, Buck, Stringfellow, John Ramberg, and Bill Rieflinwill support the record with a series of appearances this month, including a clutch of gigs at Austin’s South by Southwest festival and a potential April slot on The Late Show With David Letterman, the album won’t be given a long-term touring/promotional push. As it turns out, McCaughey’s stuck for the foreseeable future working his “day job” as a sideman for R.E.M. The groupwhich has spent much of the New Year in Vancouver with producer Pat McCarthy cutting tracks for a best-of collection and a follow-up to 1999’s Revealwill start a world tour in the summer before resuming work in the fall on the new album, slated for an early 2004 release. All of which, unfortunately, means that Down With Wilco probably won’t get the full exposure it deserves. But don’t expect McCaughey to complain.

“Playing with [R.E.M.] is really what’s kept me going the last seven or eight years. I knew I’d always be writing and recording songs in some way or another and maybe playing shows around Seattle, but R.E.M. is what’s allowed me to do stuff like Minus 5. Otherwise, I’d have to have a real job, because I found I couldn’t be scraping by anymore with a family,” says McCaughey, who’s married and has two kids with singer Christy McWilson.

The financial security of the R.E.M. gig also means McCaughey is able to indulge his passions as a small-time mogul, putting out records by friends and locals like the Model Rockets (see sidebar) and generally keeping his fingers in a number of musical pies.

And for a man who lives, breathes, and loves rock ‘n’ roll, there’s nothing quite as important as that.