In Don DeLillo’s 1985 novel, White Noise, a professor of “Hitler Studies” says of the Fhrer: “He’s always on. We couldn’t have television without him.” Since then, Hitler has annexed ever more cultural Lebensraum: the upcoming CBS miniseries Young Hitler; last year’s controversial “Prelude to a Nightmare,” an art show including Hitler’s own work; Ron Rosenbaum’s brilliant 1998 nonfiction Explaining Hitler; next week’s documentary Blind Spot: Hitler’s Secretary; and now, the wildly fictional film Max (which opens Friday, March 7 at the Metro). Written and directed by Menno Meyjes (who co-wrote the Nazi fable Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade), Max depicts Hitler as a starving young artist who only goes into politics because his rich Jewish dealer, Max Rothman (very loosely based on Josef Neumann and Hitler’s several other Jewish art dealers), doesn’t give him a promised art show.

As Hitler, Noah Taylor (the true mad genius of Shine) crafts a darkly glowing performance inspired by a childhood photo of Hitler with arms crossed and footage of his shrieking adult speeches. And John Cusack is solid as Max, a World War I vet who thinks Hitler might be great if he could channel his own war-vet rage into anti-conventional art. But the trouble with the film is that Max and Adolf seem to occupy two skew planes of existence that do not convincingly intersect. Cusack plays a grown-up version of his familiar intellectual rebel hepcat; and though the 1919 Munich milieu is evocative (Max was filmed in Budapest), Taylor’s Hitler seems to be from some eerie parallel universe.

Still, the film is the most important failure of the year, raising mind-rattling questions about the nature of art and evil.

Like the cbs series and “Prelude to a Nightmare,” Max has provoked a chorus of recrimination from Jewish groups and others who haven’t seen it. Critics of art about Hitler have two big fears: trivialization and humanization. “Why do we need to know when he dated, how he dated?” railed an Anti-Defamation League spokesperson. “[The CBS miniseries] will be Hitler as a preteenwe’ll find out he’s a bed wetter. We know who he is, we know what he didwhat are we going to learn?” The Jewish Defense League said of Max: “There is no moral justification for making such a movie.” Shoah director Claude Lanzmann goes further, saying any attempt to represent the Holocaust in art or to explain it analytically is evil, because (as Rosenbaum paraphrases it) “any answer begins to legitimize, to make ‘understandable’ that process.” Lanzmann blasted Schindler’s List; Spielberg liked the script of Max but refused to direct it because it would offend the Shoah Foundation.

Actually, we don’t know who Hitler was, and art is a way to inquire, not to legitimize. How Hitler dated is relevant: Some say the Holocaust originated with the suicide or murder of Geli Raubal, the love of his life; this heartbreak marked his final break with human reality. The CBS script (adapting Ian Kershaw’s landmark bio) shows Hitler as a kid playing cowboys and Indians and Boer War. This is not trivial: He was rehearsing for war, forming a worldview, forging a moralityjust as I was when, as a child, I re-enacted D-Day daily with my best friend, the son of German refugees. We got new D-Day toy-soldier sets from Sears every Christmas and Hannukah. The concentration camps his parents barely escaped were inspired by the mass murders of Boers and Indians, which Hitler began studying in his childhood play.

Max has been pilloried for dialogue that sounds trivializing: Max says, “C’mon, Hitler, I’ll buy you a lemonade.” In fact, in context, this is serious. Max, a liberal libertine, is teasing Hitler for his ascetic avoidance of alcohol, trying to win him over to the hootch-swilling, dame-smooching, transgressive art-making, humanist side. Max is an aesthetic and moral debate between modern artmostly Dadaismand reactionary politics, as expressed in Hitler’s own anti-modern art.

In published interviews, Cusack’s real-life father voiced the essential objection to Max: “I don’t want to think of Hitler as human.” Cusack replies, “How dare we not?” Similarly, Holocaust avenger Elie Wiesel asked Robert Jay Lifton if the Nazi doctors were humans or beasts when they did what they did. Lifton said they were rather ordinary. Wiesel cried, “But it is demonic that they were not demonic!”

Hitler was human, not demon; yet he was not quite one of us. It is virtually impossible to ignore, as Max mostly tries to do, the gesticulating politician Hitler and concentrate on his brooding human side. His best biographer, Alan Bullock, says, “Subtract politics, and there’s nothing left.” Another called him an “unperson.” Max keeps exhorting Hitler to stop being lazy (as his real dealer did) and “go deeper” into his own soul, but Hitler’s heart was a cavity. He had few true connections with humans, except as objects of manipulationa loner as a kid, he was a solo courier in World War I and a lifelong artist with zero sense of fellowship with artists of his time. His pianist pal “Putzi” Hanfstaengl said Hitler “could only play on the black keys.” Something in him was missingnot the apocryphal lost testicle, but some brain function involving human contact.

Noah Taylor and Max convey some sense of this, but fail to make Hitler seem fully human. Maybe he should be understood as partly human. Explaining Hitler puts it this way: “Consider first seeing evil as incompleteness . . . not an alien, inhuman otherness.” Or consider the devil in C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters, who complains that it’s hard to be a devil, because evil is a nullity, it gives you nothing to work with: “Everything has to be twisted before it’s of any use to us.”

There’s a clue to Hitler’s twisted nature in his thousand-odd paintings and sketches, collected in Billy Price’s 1984 picture book Adolf Hitler: The Unknown Artist (available on Amazon for $274the originals fetch millions). Though he was talented at sketching buildings, he was rejected by art schools because he couldn’t draw the human figure. The contrast between his expert drawing of a building and the inept, out-of-scale, puppetlike figures he drew on the adjacent street is startling. He apparently was defective in seeing people, except as part of a larger inhuman pattern. In power, he championed Arno Breker, a better draftsman, who turned people into forms very like the vast, impersonally heroic buildings Hitler drew. (After the war, Breker got rich painting vast, impersonal business moguls.)

Max gets all excited when he sees Hitler’s sketches of flags, uniforms, and citieshe thinks they’re a futurist fantasy. But they were his true art form. Even though many people, including the curator of the show “Prelude to a Nightmare,” believe the premise of Max, I do not share their belief that a Hitler art show would have prevented the Holocaust. From this point of view, the Holocaust was Hitler’s art show.

“It’s possible to see his vision of inferior peoples and degenerate races as perverted artistic judgments,” writes Rosenbaum. “Inferior races were the ‘degenerate art’ of biological creation.” Hitler promulgated this analogy in the notorious “Degenerate Art” exhibition, which I saw excerpted in a New York Public Library show. Stunningly, it juxtaposed the distorted figures of German avant-garde art (the kind seen in Max’s gallery) with actual photos of people with disfiguring diseases. They look strikingly alike. Hitler had fathomlessly ghastly taste in art, but the “Degenerate Art” show was a horribly, brilliantly effective artistic statement.

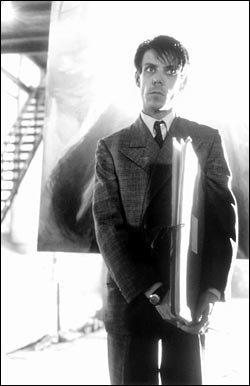

Ready to burn: one of Hitler’s architecture-minded drawings.

photo: Bundesarchiv |

The point of a slave labor camp is to enrich the enslavers, but Auschwitz sapped the Nazi economy. Its sole “success” was eliminating the labor force, which was, impossible as it sounds, Hitler’s artistic statement: a monument to a demented metaphor of cleansing and a sardonic jest, a bizarro-world mirror of Hitler’s ideal society, with its orchestras and the motto over the gate, “Work Makes One Free.” The SS is thought of as brutally efficient. In fact, like Hitler’s entire government, it was brutally inefficient, a pack of squabblesome stumblebums, satanic Keystone Kops. Some elite. The SS only succeeded aesthetically: Susan Sontag points out that it was meant to be “not only supremely violent but also supremely beautiful.” The Nazi flag, uniforms, and runic symbols were stunningly, superbly designed (as a child playing D-Day, I felt guilty that the coolest, scariest gun of all was the Luger). Hitler’s ideas were a brainless mishmash of others’ ideas, but he dramatized them with an artist’s genius. Who else could have thought of fusing Wagner, Vienna mayor Karl Lueger’s racist rallies, Wall Street, Hollywood, and

the Harvard fight song into a masterpiece of propaganda art?

Hitler’s true artnot the postcard art he scribbled as a youth to survive, but his attempt to destroy and restage societyattempted to thrust upon others the dehumanization his own nature imposed on him. Rosenbaum calls the “selections” at Auschwitz “a kind of demonic connoisseurship, [an] almost curatorial ritual . . . a kind of artistic process in reverse, a de-creation, in which humans are reconfigured, resculpted into subhumans.” It was an art that fused individuals into a howling architectural mass in rallies or inert architectural masses in death; an art of sadomasochismwhich is, as Sontag notes, “severed from personhood, from relationships, from love.” It was as if Hitler managed to take the passersby he incompetently drew, turn them into puppets, and remake them into cityscapes.

Critic Rachel Polonsky insightfully compares Hitler to Sept. 11 architect Mohammed Atta. Like Hitler, Atta was obsessed with city planninghis code name for Sept. 11 was “The Faculty of Town Planning”and with visions of New York in flames. Albert Speer said Hitler ecstatically envisioned Manhattan “skyscrapers being turned into gigantic burning torches, collapsing upon one another.” Unlike Atta, Hitler was also ecstatic to see Boeing’s Flying Fortresses burning down his own country’s cities. It saved him the trouble of burning them himself to make way for his master plan.

Even after half a century’s inundation of historical and artistic commentary, it’s still hard for us to grasp the scale and perversity of Hitler’s artistic imagination. Max is audacious and on the right track, but when Taylor growls at Cusack, “Politics is the new art, Rothman! I am the new avant-garde,” it doesn’t do justice to the immense, strange reality. Hitler’s fragmented personality and devious machinations, and the huge, mysterious holes in the historical record, call for a film with some multiple narrative form: like Rashomon or Reversal of Fortune, perhaps, presenting many contradictory versions of Hitler. That might capture in fiction the state of attempts to capture Hitler in fact.

Holocaust documentarian Lanzmann insists that only a bare factual technique is acceptable when capturing Hitler’s handiwork on film. No fancy camera angles; no art. I disagree. Facts would suffice only if he were intelligible in terms of reason. He personified unreason, and can best be apprehended in art, the less documentary the better. Max is a start, but I would ask for something farther out, like a film of George Steiner’s speculative Hitler-escaped drama, The Portage to San Cristobal of A.H., or Gravity’s Rainbow, with its lurid Geli Raubal character and doomsday vision of humans made mechanistic, its Wagnerian hallucinations. Young Hitler tried to finish an opera Wagner had left partly written; his war against humanity was militarily insane and only made sense if seen as his true Wagnerian epic.

The real missed opportunity was when the penniless Hitler was given a letter of introduction to the leading Wagner stage designer of his day: He went three times to meet him but was too cowardly to knock on the door. If only he could’ve become a stage painter, maybe he wouldn’t have gotten the idea to make Europe his stage.

We can only comprehend and thereby conquer Hitler through a conscious, successful attempt at what he spent his life failing to achieve: an act of creative imagination.