Our goal for this Spring Books issue is to read beneath the text of war. The surface plot is obvious enough: Bush is going to invade Iraq, and nothing will stand in his way. What, then, is the subtext? Why is our nation so war-bent and ready to fight? Where did all this bellicose determination come from? It doesn’t matter that most Seattle Weekly readers, and most of Seattle, are against the conflict. Bush’s America, Red America, will have its way. Iraq will fall at great cost, and the world will tremble and howl in protest. What follows are the slips, the clues, and the inferences our writers have drawn from the past year’s worth of war books.

Chessmen

Let me distill all 496 pages of Kenneth M. Pollack’s The Threatening Storm: The Case for Invading Iraq (Random House, $25.95) to a single image: Saddam is a chess piece, and America should knock him down with a flick of its mighty finger to make the game easier to play. Published last fall by a Democratic-leaning former CIA analyst (a Yalie, no less!), the book boils down to thatlet’s make chess into checkers. The world is too complicated. The Middle East is too confusing. People can’t be bothered to think about it. But after we take out this despot, everything will straighten itself outIsrael, Palestine, and those fickle Arab states with their strange customs and festering grievances whose oil we need so badly.

Absent Saddam, Pollack writes, “We would be truly free to pursue other items on our foreign policy agenda.” Items. Like a grocery-store list. Bread, milk, toilet paper, world domination. Check.

Pollack begins his book with a foreboding poem from Yeats”The Second Coming,” couldn’t he show more imaginationand concludes with John Stuart Mill, the father of utilitarianism. In other words: The inescapable ends justify the ineluctable means. And there’s no time to lose after Sept. 11, Pollack acknowledges: “[P]olls demonstrate that with each passing month, the willingness of Americans to use force to remove Saddam from power declines a bit further.” So we have to dumb down our foreign policy to achieve quick, easily apprehensible results. They have to neatly fit within a headline, a sound bite, a CNN crawl, or a photo.

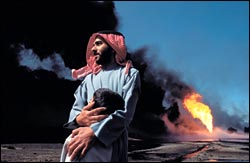

So leave it to photojournalist Peter Howe, the editor of Shooting Under Fire: The World of the War Photographer (Artisan, $35), to provide some essential context outside the tidy 35mm frame. He selects the words and images of 10 important combat photographers to show everything Pollack leaves out of his white paper. Here are scenes of what Baghdad might become: Berlin, Saigon, Hue, Belfast, Beirut, Sarajevo, Grozny, Ramallah, Kabul, and lower Manhattan on Sept. 11. The images may scorch your retinas, even if you don’t recognize all the place names.

Howe will visit the University Book Store on Thursday, March 20, and he can tell you about the scenes he’s witnessed in Northern Ireland and El Salvador. I hope he’ll show slides, since words can’t compare to such pictures. It’s the best way to honor the men and women who risk their lives to portray the horrors of war.

Although they’re also an articulate lot. Says James Nachtwey (himself the subject of an entire documentary, War Photographer), “When I was photographing the wars in Lebanon, the war in Afghanistan against the Russians, the Afghan civil war, and both Palestinian uprisings, I thought I was covering separate stories. But on September 11, 2001, I realized that I had actually been photographing one story, and this was its latest phase.”

And now it will be continued. -Brian Miller

The Three Faces of George

If you think Bush is stupid, you are. If defenders of democracy and the life of the mind don’t quit treating him like a joke, the society-shattering joke will be on them. So it’s high time to brush up on Bush with three important books that help explain why he’s so intent on taking us to war.

First and most fair-minded is Shrub: The Short But Happy Political Life of George W. Bush (Vintage, $10), by Molly Ivins, who has hung out in Bush’s circles since high school, and Lou Dubose. It gives Bush his due as an education reformer and political adept who recruited Hispanics and bridged the hate-filled cultural gulf between country-club Republicans and the Christian right. He’s also been stunningly lucky: The $2 billion tax cut on which he ran for president was paid for by the tobacco lawsuit won by his b괥 noir, trial lawyers. “This guy is not just lucky; if they tried to hang him, the rope would break.” Which explains Bush’s no-plan, faith-based strategy for Iraq: “Hey, trust me; it’s always worked out for me before!”

Mark Crispin Miller’s The Bush Dyslexicon (Norton, $24.95) is often found in bookstore humor sections, and it’s packed with rib-tickling Bush quotes, like “More and more of our imports come from overseas.” But it’s also a close, angry analysis of a coldly calculating mind. “We misunderestimate him at our peril,” says Miller. Part of that peril, for Iraqi troops, the U.N., and anyone who disagrees with his bellicose extremism, is a stunning lack of compassion.

Asked about the words addressed to him by his fellow sinner-turned-born-again-Christian Karla Faye Tucker just before her execution, Bush repeated them mockingly”Please . . . don’t kill me!” Representing the most powerful one percent of Americans, Bush finds the mortal fear of powerless people hilarious.

Miller is most noted as a critic of TV, and he ably shows how Bush’s telegenic chumminess and sly, wriggly nonanswers play brilliantly in an era of right-wing dominance of the only news medium that counts. He’s a TV pitchman, the Ron Popeil of war.

The most ambitious Bush book is the most problematic: Michael Lind’s Made in Texas: George W. Bush and the Southern Takeover of American Politics (Basic Books, $24). Lind sketches two Texan political traditions: a progressive, essentially Midwestern one based in the Hill Country, leading to LBJ, and another, essentially Southern one based in Bush’s West Texas “oillionaire” region, “the heart of the historic Texan lynching belt . . . the most reactionary community in English-speaking North America,” that gave us six Confederate generals; modern white supremacism; murderous Protestant fundamentalism; crony capitalism; a primitive, oligarchic tyranny; and Bush.

Lind is a lively writer and my favorite political type, a member of the Silenced Majority: the centrists. But he paints with a too-wide historic brush, writing: “Today’s Southern right combines the political economy of plantation owners with the fundamentalist religion of hillbillies.

So which is the real Bush? Is he the cunning, lucky fuckup (Ivins and Dubose), the dyslexic bully (Miller), or the atavistic savage (Lind)? I’d say all three. And as a Christian who could hogtie Bush’s ass in any Bible competition he cares to propose, let me pose a question: What would Jesus do? Not what Bush does. His is the Wrong Testament. -Tim Appelo

The Right War

Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman famously said war is hell, but he knew, perhaps first and best, that a short stay in hell was preferable to living in the purgatorial mosh pit of barbarism, or the eternal crucible of hell’s hot corners. War is not the antithesis of civilization; it is civilization’s nasty business. The freedoms and values of the West are preserved only by waging just wars that put evil back in its cage. Warriors like Sherman, George Patton, Ulysses S. Grant, and Curtis LeMay are the blue-collar stiffs we unleash to do civilization’s dirty work. In times like these, against enemies like bin Laden and Saddam Hussein, we need them.

This is what is argued by Victor Davis Hanson, a classics professor and war historian at the University of California, Fresno, in his remarkable collection of essays, An Autumn of War: What America Learned from September 11 and the War on Terrorism (Anchor, $12). The book is an intellectual diary of the four months immediately following Sept. 11, an almost stream-of-consciousness set of postings to National Review Online and essays for other mostly conservative magazines. Naturally, as an expert on the Greeks, Hanson has a tragic sense of man’s lot: Like it or not, evilthat great human flawis here, and we must deal with it. His essays frequently return to this theme as he sorts out the implications of Sept. 11. What results is a kind of window, and a prescient one at that, into the mentality and intellectual underpinnings of the Bush-Cheney-Rumsfeld regime in war mode. In fact, one could argue that this book is the best speech Bush never gave.

Refreshingly, Autumn lacks the president’s messianic rhetoricthough Hanson defends such zeal as necessary in a war leader. But he more broadly defines and extols the democratic and humanitarian values that America embodies. They rest on a commitment to rationalism, which has allowed the West to thrive. The events of Sept. 11 have given us more than ample reason to retaliate in Sherman-esque fashion; in fact, they mandate that we do. Civilization requires that we march to the sea via Afghanistan and Iraq, because the alternative, not doing so, is even less civilized.

For all his classical scholarship, Hanson finds more resonance in our own young nation’s history, especially the two “good” wars we fought and won: the Civil War and World War II. It is often said that armies fight the prior war. In this case, Hanson and the Bushies can only explain the ongoing war against terrorismand looming invasion of Iraqin WWII terms: Islamic fundamentalists are “fascists.” We’re fighting an “Axis.” Sept. 11 was “Pearl Harbor.” Saddam and bin Laden are Hitler or Tojo. Peace activists are “appeasers.”

The analogies are arguable, but one senses that men like Hanson and Bush, baby boomers (with WWII-veteran dads) who likely played D-Day in the backyard, have been waiting for their just war, for a time whenin the full flush of middle agethey could tap their inner Churchills. (This might be especially cleansing for Bush, whose grandfather, Prescott, was tainted by his cozy relations with Nazi financiers.) Hanson’s well-articulated and refreshingly blunt essays seem almost as if they were pre-written, waiting for the great turn of fate to bring the boomer generation its own defining moment. Well, it has, and that is a tragedy. -Knute Berger

Beltway Warriors

For months, I’ve encountered bits and pieces of admiring buzz regarding Bob Woodward’s holiday gift-giving hardcover account of the Bush administration’s first 100 days after Sept. 11. And now, I understand why.

Bush at War (Simon & Schuster, $28) is useful as insta-history, a meticulous attempt to narrate, with a pop historian’s eye for detail, what may eventually be considered a key period in Americanif not worldhistory.

Woodward, however, is no historian. He’s a celebrity journalist who got famous as an aggressive young Washington Post reporter who helped bring down Nixon. Boat rocking, however, is out these daysstenography is in. It’s become Woodward’s gravy train. For 30 years, he’s exploited his reputation to gain access to powerful men. In return for that access, he dutifully, credulously writes whatever his subjects tell him. (The book’s telling climax is his trip to interview Bush on his Texas ranch: Celebrity meets bigger celebrity!)

The result is a disservice to its subject matter, especially now. For all the narratives of Cabinet and Security Council meetings, moving from Sept. 11 through the invasion of Afghanistan, domestic security measures, and, always, the obsessions with Iraq, War is astonishingly claustrophobic. We read about what the protagonists say and do. We don’t read about the impacts of their decisionseven ones that, for better and for worse, affect millions of lives.

Just as Washington, the Bush administration, and War can’t see outside the Beltway, those of us outside the loop aren’t allowed to see back in. Woodward doesn’t help here, either. We learn that Rumsfeld has a temper, that Cheney doesn’t talk much but is a hard-liner, that Bush “leads from his gut.” That’s all. When Bush, Rumsfeld, Rice, Powell, or any of the other central players make assertions that others might consider either ignorant, open to question, or demonstrably untrue, the reader gets nothing to counter or even balance the assertions. Nowhere does Woodward use his enormous public credibility to state any of his own actual conclusions, like, “This policy was bad,” or, “That decision was effective,” or, “Their incompetence went unpunished.”

It’s not so much the book’s buzz-generating D.C. equivalence to Entertainment Tonight that galls as Woodward’s own disconnect with the outside world. As the United States slipsor hurtlestoward international isolation by attacking Iraq, War neatly illustrates the problem of unilateralismnot by writing about it but by being an example itself. Woodward became an icon of journalism 30 years ago as the consummate outsider, just as Bush came in from Texas. Whether those images ever bore any resemblance to realityhow can a president’s son be a D.C. outsiderreally doesn’t matter. Today, both are smug insiders. They deserve each other. But we deserve better.

No matter what happens in Iraq, this fall’s hardcover Bush at War II , if written, will read just the same. -Geov Parrish

High, Tight, and Angry

They may be few, but they aren’t proud. “Like most good and great Marines,” writes Gulf War veteran Anthony Swofford in his brilliant new memoir Jarhead: A Marine’s Chronicle of the Gulf War and Other Battles (Scribner, $24), “I hated the Corps. I hated being a Marine. . . . ” In Swofford’s world, the “jarhead” (named for his high, tight haircut) is an object of scorn and self-hatred, driven by a rapacious, undirected violent energy, trying to overpowerwith whoring, drinking, and extreme feats of physical and mental disciplinethe knowledge that he’s just, in the end, a dispensable grunt. The Corps supplies a channel for rage and a place where rage feedsrage at “the tragedy of our cheap, squandered lives,” at not being something more.

Suddenly made timely by the prospect of war with Iraq, Jarhead is receiving more attention than it otherwise might, which is perhaps one sliver of a silver lining in the current political climate. You can’t watch the gushy news coverage of troop buildups and tearful military farewells the same way after reading Swofford’s hellish and brutally funny account of his platoon’s months-long deployment in the deserts of Saudi Arabia 13 years ago during Operation Desert Shield.

With clear-eyed angry bemusement, Swofford describes marches in 125-degree heat, sleeping in sand holes, the obsession with pornography, and, most vividly, burning the shitter barrels. The combination of fear and boredomendlessly cleaning and reassembling their M-16s hour after hournearly drives Swofford to suicide. One irony, of course, is that the men and women charged with defending freedom and the cushy American way of life enjoy no such privileges themselves. Jarhead portrays a world of capricious and dictatorial Marine commanders whose wrongheaded decisions, in one horrific scene, nearly destroy Swofford’s unit with friendly fire.

Obviously, the military can’t operate according to the rules of a free society. But as a result, Swofford and his mates feel far more kinship with the unseen enemythe poor Iraqis also dug in against meaningless death in the middle of fucking nowherethan for the alien civilians and leaders of the country they serve. Swofford’s Marines are not rah-rah America; they are rah-rah blood and rah-rah survival. “We are soldiers for the vast fortunes of others,” Swofford writes, cynical from the beginning about what became Desert Storm. “[We] know that the outcome of the conflict is less important for usthe men who will fight and diethan for the old white fuckers and others who have billions of dollars to gain or lose in the oil fields.”

Yet it would be foolish and facile to read Jarhead as just an anti-war book. No honest portrayal of a war experience is going to be pretty. As Swofford writes, “The warrior always fights for a sorry cause.” Part of what his memoir conveys so vividly is that the causewhatever it might begets lost in war’s epic yet utterly mundane horrors. This quietly profound book manages to portray the Marine as not just a mercenary sent to do our dirty work, but as the most raw and profane carrier of a more universal human uneasethe futile urge to rise to something greater than ourselves. -Mark D. Fefer

Anthony Swofford will read at Ravenna Third Place (6500 20th Ave. N.E., 206-523-0210), 7 p.m. Tues., March 11, and at Borders Seattle (1501 Fourth Ave., 206-622-4599), noon, Wed., March 12.

How Words Made War

For a certified conservative, David Frum has earned surprisingly high praise from the notoriously left-wing American print media for The Right Man: The Surprise Presidency of George W. Bush (Random House, $25.95). As a writer by trade myself, I can see why. You have to admire a journalist/academic who could join the White House staff as a junior speechwriter in January 2001, leave in a tornado of controversy just 13 months later, and see his book about his experiences there on the best-seller lists less than a year after that. The boy’s a mover, no question about it.

Frum was hired by the White House to write on economic issues, but his claim to a place in American political history rests on his coinage of the term “axis of evil.” Asked in December 2001 by chief presidential speechwriter Michael Gerson to “sum up in a sentence or two our best case for going after Iraq,” Frum came up with a kind of tortured analogy based on the geopolitical situation in 1941, and stuck the label “axis of hate” on it. Once loosened into the memosphere, it morphed under the massaging hands of Condi Rice and Bush himself into a lunatic justification for destabilizing the entire global balance of power.

As Frum sees it, war with Iraq became a serious option because none of Bush’s other initiativeseducation, Medicare reform, you name ithad a hope in hell of going anywhere. Then, once war became an option, the imperatives of the economy and the political process narrowed his range for action even further. We’re going to war, in short, because Bush couldn’t find any other way to show he’s a leader.

Frum’s portrait of his former boss is admiring, sympathetic, always respectful, and absolutely appalling. The leader of the free world emerges as ill-informed, incurious, unimaginative, obstinate, suspicious, vindictivebut redeemed, indeed transformed into “the right man” for the job, says Frum, by his unshakable conviction that God is on his side. (Or vice versa; as Frum tells it, the distinction is irrelevant.)

If this characterization of GWB strikes you as not all that different from your own, I particularly recommend Frum’s book to your attention. (How this damning tome ended up a “Main Selection” of the Conservative Book Club I’ll never know.) You won’t learn anything you didn’t already fear you knew about Bush; but you’ll learn a lot about the sheer seductiveness of powerhow, like a black hole, the Oval Office radiates a force that distorts everything that comes within range of its influence. Watch in fascinated horror as fine minds turn to jelly, convictions bend and buckle, facts and figures turn inside out!

If you ever thought that history was a rational process, a reading of Frum’s skimpy little memoir will set you straight as effectively as plowing through War and Peace. And a lot more quickly. Since you may not have much time. -Roger Downey

Axles of You-Know-What

PRESIDENT BUSH has made it clear that reducing dependence on foreign oilthe latest Republican euphemism for weakening environmental regulations and despoiling Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refugeis among his top priorities. The prospect of invading Iraq, and the spike in gasoline prices that will inevitably follow, has heightened this sense of urgency. But if the White House and Congress really want to cut down on Arab oil imports, they need look no further than their own driveways.

According to High and Mighty (PublicAffairs, $28), New York Times correspondent Keith Bradsher’s comprehensive look at sport-utility vehicles (or, as the Sierra Club likes to call them, “suburban assault vehicles”), some 20 million SUVs are now prowling America’s streets, each guzzling gasoline at twice the rate of a compact car.

As Bradsher documents, SUVs are among the greediest, most fuel-wasting vehicles ever dreamed up by Detroit. They’re also among the least-regulated vehicles on the road, thanks to a long chain of loopholes that started back in the 1970s, when Congress exempted “light trucks”a category that includes SUVsfrom fuel-economy and environmental regulations.

Meanwhile, as stricter regulations have made cars smaller, lighter, and often less comfortable, SUVs have been allowed to evolve into veritable luxury liners. Today, they’re the vehicle of choice for well-heeled suburban Americans in search of comfort and prestige (covered by the fig leaf of off-road practicality). Even as hybrid vehicles like the Toyota Prius offer improved fuel economy, ever-bulkier SUVs are pulling down the industry average to just over 20 mpg.

Despite the rhetoric about reducing dependence on foreign oil, recent administrationsDemocrat and Republican alikehave been loath to offend Detroit by pushing for changes that could accomplish exactly that. Since 1980, the light-truck category has risen from 20 percent to 52 percent of U.S. vehicle sales. Cheap gasolinekept that way because states and the federal government are unwilling to raise gas taxes to a level commensurate with the actual costs of roadshas also contributed to SUVs’ growing hegemony on the highway. Adjusted for inflation, gas would have to be $2.62 a gallon to match its 1981 peak of $1.35. (In Germany, it’s now more than $7.)

And now, before the first bomb falls, Americans are whining because it’s around $2.

Well just wait for the war to start. -Erica C. Barnett