Adrift somewhere in all the intense scrutiny over ACT’s perhaps fatal $1.5 million debt seems to be ACT itself and its place in our community. What-ever the source of its woes, whatever the inattentiveness or perhaps even downright willful ignorance of whomever we eventually find responsible, the most galling facet of ACT’s potential closure is that we’ll be losing something of value. Not just a theater that may have let its ambitions blind its common sense, but a place that had something to contribute to what had been a thriving arts scene.

No, it has never quite gained the identity that comes with the kind of playful aesthetic reinventions of artistic director Bartlett Sher at Intiman or the who-needs- Broadway-when-you’ve-got-us? orgasmics going on over at the Rep. But ACT had found a respectableand, you might have said before these recent revelations anyway, carefulhome somewhere between the two, a catchall balance that has perhaps made it easy for pundits to dismiss the theater.

In considering the art form from every angle, ACT has played a modest role in showing how many different ways theater is being done today. It opened its various stages to readings, personable solo pieces, and festivals (including FringeACT, four days of staged readings that premiered last year with a plethora of engaging new works and will start again this Thursday, March 6). It has grabbed both intimate, pre-sold prestige piecese.g. Donald Margulies’ Pulitzer-winning Dinner With Friends (a particularly fine staging by then-artistic director Gordon Edelstein)and the premiere experiments of big names like Philip Glass (whose misfired but not uninteresting opera In the Penal Colony played a few seasons ago). Better, its keen-eyed Bullitt cabaret space welcomed up-and-coming names that continue to be small forces in American theater: Pamela Gien’s The Syringa Tree has met with adoring crowds in New York, and a relationship with lush lyrical playwright Dael Orlandersmith (The Gimmick, Yellowman) has added immeasurably to local theatergoing.

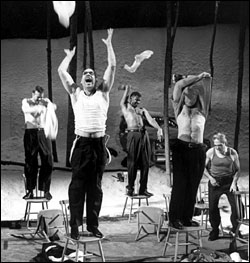

Maybe ACT’s multistage vision was too much to take onyes, it overreached. Looking back, its lavish devotion to cult figure Charles Mee, the idiosyncratic playwright behind wild love-’em-or-hate-’em talk-fests Wintertime and Big Love, probably cost a pretty penny better spent elsewhere. And maybe an expensive endeavor like O’Neill’s melodramatic epic Mourning Becomes Electra (another Edelstein effort I personally loved) wasn’t a wise choice for a company still trying to offset the $30 million downtown home it acquired after moving from its old Queen Anne digs. But at least it reached, and in all directions.

When it misfired, obviously, it really misfired. The Education of Randy Newman, its new musical based on the songs of the esteemed pop composer, was a big show meant to appeal to mass audiences; the sight of bright-faced actors tarting up Newman’s dark gems wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea, though, and certainly didn’t score points in the innovation department. Whatever the relative value of the Newman musical, however, the fact that ACT threw dollars at it is hardly a sinand if it is, it’s one that many theaters are committing and for a worthwhile purpose: generating money for less marquee-friendly ventures. Big shows can bring in big funds, and it’s naive to suggest that any company should be able to operate solely on impassioned $2 affairs created in somebody’s basement. Newman had the potential to bring in even more revenue and fund the appearance of even more Pamela Giens and Dael Orlandersmiths. That ACT may no longer be able to do so is our loss.