Many of the world’s fine-wine regions provide scenic window dressing for their pricey products: Germany’s Mosel offers real castles on real crags, France’s more bourgeois Bordeaux chⴥaux (mostly faux) among the vineyards; California’s Napa makes up in architectural overstatement for what it lacks in history.

Washington’s Walla Walla Valley, home to many of the most admired and most expensive Northwest wines, is distinctly lacking in the trappings of romance. The view, at least along eastbound U.S. Highway 28, is drab: flat farm fields on your right, low hummocky hills on your left, and nothing on the horizon ahead but a grain elevator or two.

In fact, there are scenic beauty spots in the Walla Walla AVA (the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms acronym for a federally recognized American Viticultural Area); there’s even a chⴥau of sorts: the Italianate Leonetti estate on Foothills Lane east of town. But the estate’s not open to the public, and you won’t find most of the beauty spots without a good map and diligent looking.

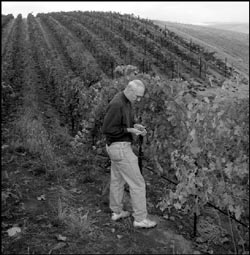

It’s not that Walla Walla winemakers are hostile to visitors, exactly; but many if not most of them were farmers before they were winemakers, with generations of farmers before them. And farmers, while friendly folk on the whole, don’t go out of their way to encourage strangers driving up to the homestead.

A HUNDRED YEARS before wine grapes appeared on the scene here, the Walla Walla Valley was growing wheat and peas, onions and fruit. A lot of the families that put down roots then are still a presence today, at least as names on title deeds to the land, and often as working farmers as well.

When pioneers like Gary Figgins of Leonetti (the name honors his Italian immigrant maternal grandparents) and Rick Small (fourth generation of the name) showed that a few well-grown grapes could produce a handsome profit, their neighbors took note; when wheat and apples ceased to provide a sure return on investment, some of those neighbors saw the virtue of “diversification” and began planting grapes in a small way themselves.

After three or four generations of prosperity, the old established farm families of the Walla Walla Valley were pretty diversified themselves, with bankers, attorneys, educators, physicians, and other professionals salting the ranks at family reunions. By the late 20th century, keeping at least some of them “down on the farm,” the root of family prosperity, was becoming a serious concern. Grape growing and winemaking came along at just the right moment: Here was a branch of farming cool enough to attract a generation that had gone to university, backpacked the world, and found the thought of a future devoted to mere grain, fruit, or cattle a bit lacking in pizzazz, not to mention peer cred.

All the will and calculation in the world won’t make grapes grow well where they don’t want to. But it soon transpired that the notable early vintages produced by Small’s Woodward Canyon Winery and Figgins’ Leonetti Cellars were no flukes.

GRAPEVINES NEED TO soak up a certain number of calories of heat to produce fermentable fruit; the amount is measured in units called “degree-days,” which measure not extremes of temperature but the total amount of heat available over a whole growing season. Although normal summer highs and winter lows are close to the limits of what vines can tolerate, the valley of the little Walla Walla River and its tributary creeks offers ample degree-days to bring grapes to ripeness, while the surrounding highlands of the Snake River plateau and Oregon’s Blue Mountains squeeze ample moisture from the Pacific weather systems that blow into the valley through the Columbia Gorge.

In some lucky spots—mesoclimates, in winemakers’ jargon—it offers a bonus: a long growing season, with serious frost usually absent until December. Woodward Canyon’s Rick Small believes it’s this prolonged “hang time” that gives the best Walla Walla grapes their extraordinary character. “By the end of September you have enough sugars, and from then on, days are cool enough that you don’t get too much sugar [which produces a rank-tasting, too-alcoholic wine] and nights are cool enough that you don’t lose a lot of acid [which produces a flabby-tasting wine, short-lived in the bottle]. I’m convinced that waiting those last two or three weeks for ripening to run its course is what allows the special character of each vineyard to come through in its wine.”

It doesn’t hurt, either, that growers like Small and Figgins are ruthless about keeping fruit yields to levels that growers elsewhere consider absurdly low: One and a half tons of fruit per acre is considered suitable; 3 tons—the level usually considered minimum for economic winemaking—they look on as getting dangerously high.

Low production per acre guarantees maximum concentration of flavor; it also means a high price per bottle. Makers of premium Walla Walla wine—and that category accounts for most of the production—have had to take a lot of kidding about making wine that only wine critics and rich wine connoisseurs can afford. But given their belief that crop size is an essential key to quality, there’s no way to make their wine more cheaply.

And, unfortunately for the thirsty masses, no incentive to: Much of the best Walla Walla wine is sold direct to consumers, who vie for a place on the wineries’ mailing lists and impatiently wait for an increase in their allocation, never mind the price. A good deal more is sold to knowledgeable visitors on-site, or, for vintners who don’t want to be pestered by tourists, through tasting-room storefronts downtown.

Most irritating of all, Walla Walla wine is so much in demand that many vintners don’t even see the necessity of supplying free sample bottles to the press. How humiliating to have to attend public tastings, notepad in hand, and rub elbows with people who can afford to buy wine that you can’t!