“The hardest thing for an executive director to acknowledge is that she has not been able to keep the organization funded.” So started a surprising e-mail sent around in late December by Jean Colman, head of the Welfare Rights Organizing Coalition. Or, rather, the former head. Colman announced in the e-mail that the nearly 20-year-old organization was laying her off, along with a couple other members of its small staff, leaving only a few part-timers and volunteers to carry on its work of advocating for welfare recipients and helping them negotiate the often-maddening bureaucracy.

Already struggling with dwindling donations, the coalition suffered a fateful blow when it lost a couple of key grants. Colman’s cold comfort is the fact that almost every nonprofit in town can relate to her pain. The bruising economic climate has slowed both public and private funding, leading to sometimes-dramatic cutbacks even at institutions that have been mainstays of the nonprofit world.

“When the Casey Foundation—that hallmark of nonprofits—lays off 30 people, you know something’s wrong,” Colman observed shortly after her e-mail announcement. At the time, the Seattle-based foundation known as Casey Family Programs, which provides direct services to foster children nationwide, was laying off 30 people locally and 30 more around the country. Last week, the foundation announced much more severe cutbacks: the closure of 10 of its 26 offices, including one in Tacoma, and the elimination of 250 jobs.

THAT’S A REMARKABLE step for an entity that was endowed with billions by founder Jim Casey, the United Parcel Service magnate. All of its money is, however, invested in the stock market, which, of course, has taken a gigantic tumble. (Casey spokesperson Ida Hawkins says the stock market dive is not the only reason for the layoffs, but it is a reason.)

Another prominent institution to falter is the Lifelong AIDS Alliance, the main AIDS group in town. This month, the alliance laid off nine staffers, more than 10 percent of its workforce, and for the first time in its 15-year history (to be precise, the history of the two groups that merged to create the alliance—Chicken Soup Brigade and the Northwest AIDS Foundation) is going to cut services to clients.

In his Capitol Hill office, executive director Chuck Kuehn says that the organization is considering delivering meals less frequently or putting less in the grocery bags it gives out. It might also cap the number of people served and start waiting lists.

“We had to stop bleeding the cash,” Kuehn explains. The alliance had been raiding its reserves to cope with two years of deficits. The reserves have fallen from $1.5 million to $400,000.

“The problem for us has been reductions in individual giving,” Kuehn continues. At one time, the alliance’s predecessors raised more than a million dollars a year from direct mail. This year, the organization expects less than half that amount. The total raised from the group’s biggest fund-raiser of the year, its annual walk, dropped $100,000 last year. Kuehn believes that complacency over AIDS has been a factor in the alliance’s financial woes, but the recession has exacerbated the situation. The organization is conducting a telephone campaign targeting prior donors, and those being called are frequently saying they’d like to help but are out of work.

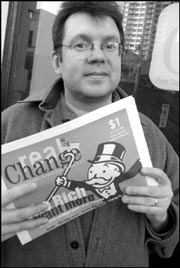

It’s a similar story, on a lesser scale, at Belltown’s Real Change, the homeless advocacy organization that puts out the newspaper by the same name. It is laying off a couple of people and closing Street Life, the studio and gallery it runs for homeless artists. “Donations are just down, really down,” says executive director Tim Harris. The holiday season of giving normally brings in about $10,000. This year turned up about $1,000. Unfortunately, the organization remodeled its office in better times and ended up spending more than it thought, eating into reserves that are now almost depleted.

Making himself at home in a little 1970s-style lounge area created by the remodel, Harris illustrates what a difference a few years can make. Not long ago, Real Change received a $25,000 check out of the blue from a Microsoft millionaire who picked the newspaper off the street and decided to help. Another Microsoft donor sent over $10,000. Neither, he says, are in a position to contribute at that level today.

In fact, the larger donor, Andy Himes, is now trying to raise money himself as the head of a nonprofit he started after leaving Microsoft, called Project Alchemy, which uses technology to help grassroots activists. He says he’s doing fine but is having a lot more coffees than he used to with potential donors to raise the same amount of money.

The good news, though, is that he’s still giving money, if a lot less of it, not only to his own organization but to a number of others. He’s one of a new generation of philanthropists born of the tech boom who see themselves as more than cash cows; they want to become personally involved in the causes they support. And Himes’ example suggests that such involvement might be an enduring piece of local philanthropy, whatever happens with the economy. “I’ll be involved the rest of my life, helping nonprofits I really care about,” he says. “That’s going to be true whether I have any money to give away or not.”

AT THE SAME TIME, individuals never rich enough to call themselves philanthropists also are continuing to give what they can. Atypically, United Way of King County is on track to raise slightly more money than last year with its campaign that concludes in June because of people like Boeing workers. Boeing has laid off thousands of workers in the past two years, and yet the company increased its contribution by $1.85 million to United Way. It’s due not to the corporate contribution, which declined slightly, but to that of employees. “A lot of their former co-workers are out of work, using the services of the agencies we support,” says United Way spokesperson Adam Bashaw. “Folks are really digging in deep.”