Why should we assume people get worse [with age]? I think you should just get on with it. Look at Paul Newman. And the Sufis think people get better, y’know? Every day is a new day, so I just look forward to it. And you can’t walk around with expectations anyway. I don’t like to know where we’re going, actually. Because you always end up somewhere interesting. If you have a specific aim or target, and then you arrive at that point—whatever, the creation of a project—it’s like, boring! There’s no fun in that somehow, is there? There’s no surprise in it. There’s no chance in it. This [career] is a construction of chaos, really.

—Joe Strummer, N.Y.C., October 2001

On Dec. 22, 2002, former Clash frontman Joe Strummer’s chaos theory—or, to put it more clinically and accurately, a heart attack—caught up with him. While early media coverage suggested that he passed away in his sleep, the latest report from the BBC indicated that he “collapsed at his home in Somerset [England] after taking his dog for a walk. . . . His wife, Lucinda, is said to have tried to resuscitate him on the kitchen floor but was unable to revive him.”

In a weird, admittedly morbid, and perverse sense, this is perfect. No doubt Joe himself, sitting up on high somewhere this very moment, is chuckling over the ludicrously middle-class nature of the circumstances surrounding his demise, this irascible, uncompromising punk firebrand decidedly not going out in a classic blaze of rock death glory. No fiery auto crash. No messy blood-and-syringe overdose. No onstage electrocution. “Bit of a cosmic giggle ‘ere, innit?” Strummer remarks, as he passes Joey Ramone a heavenly spliff. . . .

But make no mistake, the glory’s there for Strummer—born John Graham Mellor on Aug. 21, 1952—just the same. Within hours of word of his death hitting the airwaves and the Internet, tributes and testimonials flowed from the famous (Bono called the Clash “the greatest rock band. They wrote the rule book for U2”) and the not-so famous (the fan Web site Strummer News would log over 15,000 condolences from all over the world for its cybercard at www.strummernews.com). Plans for memorials and tribute concerts got under way at points across the globe, including one in New York City where a huge candlelight gathering ultimately was held the night of Dec. 26 at one of Strummer’s favorite East Village haunts, Niagara (Avenue A and 7th Street); fans would continue to flock to the site throughout the weekend, toting candles, photographs, flowers, and other symbols of their grief and affection.

Meanwhile in London, a spokesperson for Strummer’s family requested that in lieu of floral tributes, money should be donated to the forthcoming Nelson Mandela SOS concert in South Africa, which is being staged to raise funds for AIDS campaigns in Africa. (Strummer, who was slated to appear at the Feb. 2 multiperformer concert along with Bono and Dave Stewart, had already penned the song “48864” in Mandela’s honor.) At press time, no public statements had been made by any of the ex-Clash members, while on the official Joe Strummer and the Mescaleros Web site (www.strummersite.com), a posting, dated Dec. 23, read simply that “Joe Strummer died yesterday. Joe is survived by his wife, Lucinda, two daughters, and one stepdaughter. They request privacy at this harrowing time. . . . Our condolences to Luce and the kids, family, and friends.”

Media pundits, for once caught without the safety nets of their “ready rooms” (code name for where newspapers maintain extensive files of pre-mortem celeb obituaries), penned genuinely heartfelt and spontaneous memorials themselves. The one written by Milo Miles in the Village Voice seemed to best sum up Strummer’s legacy with the Clash:

“[Strummer] knew what the perfect rock band should be and lived when he could make it happen. The beat should be fast and ferocious, as hyper and relentless as the old rockabilly jitters and the new punk mania. Strummer recognized that rock had barely explored its political possibilities, and there was no reason why love-and-work tunes could not be set in English society and ripped from the headlines. Rock also provided a meeting ground for black and white sounds, and Strummer grasped that the newly militant reggae would strengthen the bones of rock as the blues had a generation earlier. . . . Strummer was the political chairman of the gang, and he made sure their activist program was vivid if vague: Be proletarian, pro-revolt of the disenfranchised in all nations; show reflexive distrust of authority leftist and rightist, savvy skepticism about mass media and willingness to co-opt it; call your blockbuster triple album Sandinista! [The] Clash made fans think about subjects unimagined in the Sex Pistols’ universe—or the counterculture’s for that matter.”

Funny how things work out. In November, the Mescaleros had completed a hugely successful U.K. tour (at a London show, Strummer’s erstwhile bandmate Mick Jones turned up for a three-song encore of Clash tunes) and were set to start working on their next album. The four ex-members of the Clash themselves had already been tapped for a March induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and were rumored to be planning a one-off set at the festivities. And Strummer, while remaining firmly anti-nostalgist and anti-reunion cash-in, had clearly come to a comfortable reconciliation with his storied past, liberally sprinkling Clash material into Mescaleros set lists.

Indeed, over the past three years there has been a massive upswing in awareness of and popularity for all things Clash, and by extension, Strummer. Sony issued a live Clash album and remastered the band’s entire back catalog; an outstanding Clash documentary film (now available on DVD), Westway to the World, appeared; and the Clash received the prestigious Ivor Novello Award in 2001 for “Outstanding Contribution to British Music.” (One sour note was struck earlier this year when the Clash approved, for a reported fee in the neighborhood of $500,000, the 45-day use of their signature song, “London Calling,” in a TV ad campaign for Jaguar cars. This caused no shortage of gritted teeth and mutterings of “sellout!” among Clash hardliners. In an online chat, Strummer defended the decision, saying, “We get hundreds of requests for that and turn ’em all down. But I just thought Jaguar . . . yeah. If you’re in a group and you make it together, then everyone deserves something. Especially 20-odd years after the fact. It just seems churlish for a writer to refuse to have their music used on an advert and so I figured out, only advertise the things you think are cool. That’s why we dissed Coors and Miller. We’ve turned down loads of money. Millions over the years. But sometimes you have to earn a bit, so everybody gets some.

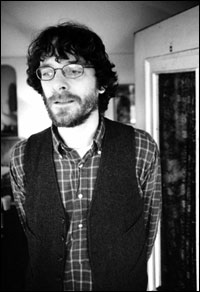

SO—WHAT BEFITS a legend most? At the time Strummer uttered the quote at the beginning of this article, he was pushing 50 but thoroughly on top of his game and enjoying a fruitful new phase in his long-standing rock ‘n’ roll tenure. The Mescaleros’ superb second album, Global a Go-Go had come out on Hellcat/Epitaph about a month earlier, and interviewed by yours truly in his dressing room a few hours before a sold-out show at N.Y.C.’s Irving Plaza venue, Strummer was the very image of sanity and health (if you don’t count a cold and bad throat picked up while on the road). In fact, he was downright feisty, fielding my questions with the fire and spunk of someone at a debating match, not another I’ve-answered-all-this-before rock-mag grilling. He was also quick with the wit, at one point derailing some of my more anal archival queries with a good-natured, “Don’t you want to know when the Clash are going to get back together?”

My most abiding memory from our conversation, however, is of when I innocently uttered the phrase “spokesman for a generation.” Strummer, who’d been sipping herbal tea and sucking on throat lozenges in between taking deep drags from his roll-ups, fixed me with a glare, walked over to a trash can and hocked up a noxious looking wad of black goo, then barked into my face.

“I’m not a spokesperson! Never was to anybody. They can hose off, man. I mean it. That’s a load of horseradish. [Pointing to guitar] I’m happy to get that box and figure out something to do with it. I get rid of my opinions! Because some clever guy said, ‘If you have opinions, you cannot see.’ Meaning that opinions will kind of horse blinker you to see the truth about any situation. [Cackling, with evil journalist-baiting twinkle in his eye] Opinions aren’t worth the paper they’re written on!”

He was right. Free your mind, and the rest will follow. An outspoken, big-hearted, enlightened rock ‘n’ roll patriarch to the end—that’s the Joe Strummer I’ll always remember. Veteran rock photographer Bob Gruen, who published a book of his Clash photos in 2001, recently posted the following brief but heartfelt testimonial on his Web site. I think it’s fitting that it be the last word here.

Writes Gruen, “I’m in shock over the sudden death of my friend Joe. He was the strongest of men, a real inspirational leader, a guy who never seemed to tire of listening to people and talking to them, learning and teaching all the time. He had true compassion for everyone he met. He was the nicest and also the most fun loving person I have ever known.”

![Strummer: "I'm happy to get that [guitar] and figure out something to do with it."](https://www.seattleweekly.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/1167511.jpg)