ABOUT SCHMIDT

directed by Alexander Payne

opens Dec. 20 at Uptown

ALEXANDER PAYNE opens this toxic, rewarding character study with a tour of downtown Omaha guaranteed not to cheer the Visitor’s Bureau. The architecture is gray and unpromising, although the camera’s prowl accelerates as it circles Woodmen of the World Towers, Omaha’s Taj Mahal of insurance.

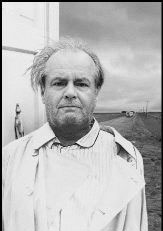

Inside the building, watching a grim-faced Warren Schmidt (Jack Nicholson) sit out the last second of his 40-some-year career gauging the life expectancy of others, the camera’s relentless scrutiny almost slams him back in his chair.

It’s not a bad metaphor for how retirement hits Schmidt, leaving him with a faintly queasy “What now?” To his doll-like wife, who has ruled his life with a porcelain fist (the man has been trained to pee sitting down), it’s the dawn of a whole new chapter: just Helen and Warren with their new 35-foot Winnebago waiting in the driveway.

To Schmidt, the idea is living death, since he’s decided that he hates everything about his wife of 42 years—the way she sits, smells, eats, and interrupts. (Payne demonstrates each of these irritations.) Still, her sudden death from a blood clot early in the movie is Schmidt’s second massive shock within weeks. For all his bravado, it leaves him rudderless.

The funeral brings home only child Jeannie (Hope Davis) and her Colorado water-bed-salesman fianc鬠Randall (Dermot Mulroney). He’s an erstwhile booby brimming with schemes to double Schmidt’s—or anyone’s—money. Just thinking about Randall, with his mullet, his 3-inch-wide mustache (outdoing Elliott Gould’s in M*A*S*H), his platitudes, and Jeannie gives Schmidt a reason to live: He’ll break up this marriage and, incidentally, bring Jeannie home to keep house. (Under the widower’s care, every once-immaculate surface is now buried under Hungry Man dinner debris and worse.)

SO BEGINS SCHMIDT’S Denver-bound Winnebago road trip across America, fueled with rage from his discovery of a mild little secret of Helen’s and guilt that, at 66, his freedom now feels as empty as it does.

All this, and way too much more, Schmidt confesses in a series of “Dear Ndugu” letters to the 6-year-old Tanzanian orphan he has impulsively adopted through a television appeal. For $22 a month, it’s the cheapest therapy around. In voice-over, Schmidt pours out the tamped-down emotions of a lifetime to this uncomplaining, if baffled, nonreader half a world away, whom he’s seen only in a photograph.

For this look into the abyss, Nicholson slips out of the shell of mannerisms that have become his identity and refuge for so long, and the results are towering. Yet in the rush to praise Nicholson’s strength and simplicity here, it’s fair to remember that Sean Penn has directed him into this kind of honesty twice before, in The Pledge and The Crossing Guard.

The wild inappropriateness of the Ndugu letters, written partly in the business-speak of Schmidt’s old world, partly in pure bile and bewilderment, are actually the film’s gentlest humor. Its widest stripe of contempt is saved for Randall’s family, who seem never to have left the ’70s.

Headed by Randall’s twice-divorced mother (an impeccable Kathy Bates), who confuses confession with conversation and is proudest that her son has inherited her own lusty sex drive, they are a noisy, cheerful gang of low-rent self-helpers, and Payne shows them no mercy.

Mullets, water beds, hot tubbing today? It’s a peculiar feeling to be so uncertain about a film’s period, but Payne and his usual writing partner, Jim Taylor, who sharpened every point in their earlier, brilliant Election, must know something we don’t—that Denver is its own Glocca Morra.

It’s certainly another world for Schmidt, who seems about to implode when he must finally speak up about Jeannie’s place in Randall’s graceless clan. If Payne only had Schmidt’s charity, it might soften the film’s bitter aftertaste of condescension, gold-standard acting notwithstanding.