Paige Elizabeth Miley was a 21-year-old prostitute back in 1983. It was a cloudy fall night when, Miley says, she talked briefly with a man who would later be accused of four of the 1982-84 Green River murders. The man asked where her “tall, blond friend” was, and Miley guessed then and there that he probably was the abductor of fellow prostitute Kim Nelson two days before. That was the only time they had worked together along the so-called Sea-Tac Strip—the commercial area east of Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, along what is now International Boulevard in the city of SeaTac.

Today, Miley is a 40-year-old heroin addict with more than 300 arrests behind her, a prison inmate doing 12 to 34 months for burglary and forgery in Nevada. She also is about to become a key witness in one of the nation’s most notorious murder cases. Authorities want to depose Miley before the trial. Among other reasons, they fear she might be a possible future victim of homicide or drug overdose and not live long enough to testify against Gary Leon Ridgway, the Auburn man the King County Sheriff’s Department and the King County Prosecutor’s Office hope to prove was the one and only Green River Killer. By including Miley’s story and similar other collateral evidence, the prosecutors suggest that Ridgway alone was responsible for all 49 Green River murders, even though he’s charged with only four.

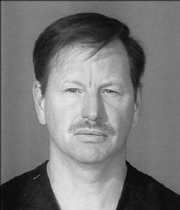

Now 53, Ridgway was a longtime employee at the Kenworth Truck factory in Renton when he was arrested on Nov. 30, 2001. Based on a saliva sample he gave in 1987, police had obtained new DNA test results that tied him to sperm found in three of the victims—Marcia Chapman, 31, Cynthia Hinds, 17, and Carol Christensen, 21. (DNA tests of sperm found in Opal Mills, 16, were inconclusive, but her body was found near Chapman’s and Hinds’.) The authorities have argued that the DNA results are accurate far beyond any random chance, given that the women were killed so soon after the sperm were deposited. The defense intends to attack the science of the new DNA technology used in the case.

Officially, King County authorities say the Green River Killer claimed the lives of 49 women during an 18-month period in 1982, 1983, and early 1984. (See list, page 23.) The death toll could be far higher. An almost equal number of similar unsolved murders are under review by the defense. Like Nelson, most of the official 49 victims disappeared from the Sea-Tac Strip.

The decision to include Miley’s claim of her brief encounter with Ridgway and evidence from the 45 Green River cases in which he is not charged is one of the main reasons Ridgway’s defense could cost King County as much as $4 million to $6 million. Costly, too, is the related decision by the King County Prosecutor’s Office to seek the death penalty.

“We will not plea bargain with the death penalty,” King County Prosecuting Attorney Norm Maleng said last December. Maleng might have thought he was seizing the moral high ground. But the consequences of that posture are profound: Without a confession in exchange for a life sentence instead of death, the community might never know what really happened in the worst serial-murder case in American history, because a cogent case can be made that Ridgway might not be the only person responsible for the murders. While putting Ridgway to death would satisfy some narrow—in some cases, political—ends, it would leave unresolved the question of whether someone else is still out there, still killing.

IN NOTIFYING THE COURT last April that his office would seek the death penalty, Maleng veered sharply from the course adopted in a similarly horrific murder case in Spokane. There, prosecutors assessed the costs and benefits of seeking the execution of Robert Yates and decided that bargaining for information, by granting him his life, was worthwhile to establish what happened to 13 women who were his victims between 1975 and 1998. Yates did eventually receive the death penalty, last month in Pierce County, for two other murders. The uncertainties are even greater in the matter of the State of Washington v. Gary Leon Ridgway. There are, for example, seven women among the official 49 who are still missing, as well as four whose skeletal remains have never been identified. There also are as many as 52 other women who might have been killed by the person or people responsible for the Green River murders—many after Ridgway was first identified as a suspect in 1986. This is according to the police themselves, who long ago admitted that, barring a truthful confession from the actual killer or killers, there is no certain way to know who should be on the list.

The prosecution of Ridgway is an unmistakable attempt by authorities to close the book on the Green River case once and for all, so they can say to the public that the nightmare is finally over. The outcome has political consequences for Maleng as well as Sheriff David Reichert, both of whom are elected officials. By implying that Ridgway is the killer, Maleng’s office can be seen as finally having brought the nation’s worst serial killer to justice. Reichert, the first detective on the scene when the case began two decades ago, who eventually served as lead investigator on the multijurisdictional Green River Task Force and who has kept in touch with some victims’ families ever since, could brandish Ridgway’s scalp as a satisfying personal and professional accomplishment that couldn’t hurt if he decides to run for governor. (Neither Reichert nor Maleng would comment for this story.)

The prosecutor’s office thinks that Miley’s story and the evidence of several other so-far-uncharged Green River disappearances might prove two major components of the state’s case: the identity of the perpetrator, of course, and “aggravation,” the element necessary to seek the death penalty. The state has argued that the multitude of murders shows a “common scheme or plan,” an effort by Ridgway to become a successful serial killer of women. And by serving notice that it intends to use evidence from uncharged crimes, the prosecutor’s office has required the defense, too, to investigate all of the Green River murders, as well as all other similar slayings. That covers a wide swath of recent history, and it’s one of the main reasons the defense is costing so much. So far, the documentation provided to the defense includes details on more than 100 cases. Ridgway’s team is spending a lot of time and money to prove that he could not have committed most, some, or even any of the Green River murders. His lawyers are Anthony Savage, Mark Prothero, Todd Gruenhagen, Michele Shaw, Eric Lindell, Fred Leatherman, and Dave Roberson.

If at least some portion of the high defense cost is the result of the no-plea- bargain decision made early by Maleng, public comments last June by his chief deputy, Dan Satterberg, are particularly unpalatable. Satterberg thrust the responsibility for the high cost of trying Ridgway onto Ridgway himself by characterizing his taxpayer-financed defense as “not just a Porsche [defense], it’s an entire Porsche dealership.” Satterberg glossed over the fact that the prosecutor’s office had an opportunity to obtain a plea bargain that, besides possibly clearing up numerous mysteries, might have saved taxpayers millions of dollars. Rightfully, the defense team howled: They contended that Satterberg was trying to poison the jury pool by implying that Ridgway was the proximate cause of the county’s current budget woes—the implication being that Ridgway’s right to a fair trial had caused the county to close its parks and cut social services. Doubtless, Satterberg would have preferred a “Chevy or Ford defense,” as he termed it, because that would have made it far less likely that some of the many holes in the state’s case would be exposed. Satterberg declined to comment for this story because, he said, “a trial date has now been set.” That date is March 16, 2004.

MILEY’S STORY IS illustrative of some of those holes, but it’s not the only weakness in the case. Several former prosecutors from Maleng’s office have privately said they would love to defend Ridgway, particularly as long as the prosecution seems bent on establishing that Ridgway is the one and only killer.

Miley’s story seemed straightforward enough, at least at the time: In 1986, she was interviewed in Las Vegas by two detectives of the Green River Task Force, Matthew Haney and Randy Mullinax. She identified Ridgway’s photograph from a montage and told the detectives that around the first part of November 1983, the man in the photograph had asked her where her “tall, blond friend” was. This encounter took place only two days after 6-foot prostitute Kim Nelson—”Star” to her friends—disappeared from the so-called Sea-Tac Strip of motels and other businesses near the airport, when Miley left her alone for half an hour. Since this was the only time she and Nelson had worked the strip together, Miley claimed, that suggested that the man was responsible for Nelson’s disappearance. That half-hour window is vital evidence for the prosecution because it supports the notion that Ridgway was in potentially deadly proximity of a victim.

At the time, Miley told the detectives, she assumed that Nelson had been taken by the Green River Killer. The killer’s depredations were the talk of the Strip, and she almost immediately called the police. A detective associated with the then-small task force led by Reichert interviewed her in the first week of November 1983. Almost three years later, in the Las Vegas interview with Haney and Mullinax, Miley claimed that she told this detective of her suspicions and provided the number of the man’s license plate.

If such a license-plate number was in fact provided by Miley, the police had a potentially vital clue to the identity of the killer as early as November 1983, whether it was Ridgway or someone else. However, either Miley was wrong about providing the plate number, or it got lost in the paperwork blizzard that was swirling around Reichert at the time, because neither Haney nor Mullinax had any record that Miley ever gave a tip on the plate. They tried to induce Miley to recall it, eventually resorting to hypnosis, to no avail.

It is as obvious today as it was in 1986 that such a license-plate number would be quite useful in either linking or ruling out Ridgway, at least in connection with Nelson, both then and now. The detective who first interviewed Miley, now retired, says he doesn’t remember whether Miley gave him a plate number or not and, in fact, doesn’t remember Miley at all. This is either an important impeachment of Miley’s credibility or the effectiveness of the police investigation, or both, and it could damage the state’s case significantly.

“What did the detective say when you gave him the license-plate number?” Haney asked back in 1986.

“He said he’d check it out,” Miley said. “Then I got back with him, and he said it wasn’t anything.”

JUST BECAUSE SOMEONE saw Nelson with Miley doesn’t necessarily mean he is the killer, of course. But including Miley as part of the evidence against Ridgway assists the prosecution in a critical area. Nelson’s skeletal remains were found near the junction of Interstate 90 and state Route 18 in June 1986. Miley’s story provides the prosecution with a way to link Ridgway to the so-called I-90 “cluster” of victims.

That appears to be the state’s strategy—to find ways to link Ridgway to each of eight “clusters” of victim remains. Once a link is made to a cluster, it logically follows—if you believe Ridgway is the only perpetrator—that Ridgway is likely to have killed all the victims in the cluster. And having established Ridgway’s links to each of the clusters, it follows that Ridgway must be the one and only. To that end, the state has sent a plethora of physical evidence to various laboratories in an effort to link Ridgway to the various clusters. But even if evidence tying Ridgway to some or all of the clusters is finally unearthed, it doesn’t mean that Ridgway alone is the killer. It’s possible two or more killers, each knowing of the other or others, could have used the same locations to dispose of bodies.

THE IDEA THAT there is one killer stems from police analysis in 1982, when the first dead women were found in or near the Green River in Kent. At the time, police concluded that the modus operandi associated with the river victims showed that there was a single person responsible. That analysis has been maintained in primacy to the present day, and it has formed the basis of the prosecution’s theory of its case, even though it has been severely tested by subsequent discoveries of the skeletal remains of so many other dead women.

Several experts, including Pierce Brooks, a Los Angeles Police Department serial-murder expert, and John Douglas, the FBI’s storied profiler, repeatedly cautioned that more than one killer might be involved. Douglas, in fact, eventually concluded that a pair of so-called “tandem killers”—similar to Angelo Buono and Kenneth Bianchi, who were cousins—were most likely to be involved. On this note, it is worth recalling that King County Detective Tom Jensen, who has laboriously accumulated and maintained the Green River files for the past decade, tried to prick the balloon of official euphoria that attended Ridgway’s arrest last year.

“There’s one thing people keep leaving out,” Jensen said at the time. “What if he didn’t do them [all]? If it turns out there’s more than one killer out there, we’d be derelict in our duty to not try to find them.”

THE SINGLE-KILLER theory was powerfully bolstered by the analysis of former King County Police and state attorney general investigator Robert Keppel, who was one of the Green River Task Force’s primary consultants. Almost from the beginning, Keppel, who investigated the Ted Bundy murders in the years before the Green River crimes, insisted that the Green River murders were the work of a single person—someone very much like “Ted,” Keppel said, someone who was motivated by a desire to humiliate his victims.

There are problems with Keppel’s analysis, however. For one thing, Keppel based his assessment of the killer’s motivation on his own experience with Bundy. Just because Bundy wanted to humiliate his victims (who were not at all like the Green River victims in background and lifestyle) didn’t necessarily mean that the Green River Killer wanted to do the same thing. Indeed, an assessment of most of the Green River crimes seems to indicate that the killer or killers wanted to conceal the victims, rather than display them, which is more often the situation among murderers who seek to humiliate.

Even more problematic with the single-killer theory is the pattern of disposing of the bodies. Initially, when the river victims were discovered in July and August 1982, Keppel believed that the perpetrator was a person who had familiarity with the so-called Atlanta child killings attributed to Wayne Williams. “The guy’s a reader,” Keppel said at the time, meaning that the Green River Killer had read of Williams’ supposed penchant for putting the bodies of his victims in water to destroy trace evidence. (It’s therefore ironic that some of the strongest pieces of evidence against Ridgway come from the DNA contained in semen that was not washed away by the river.) But Keppel’s pronouncements came before any of the other, non-river victims were discovered. Indeed, the supposed single-killer pattern appears to evince a killer who put the first supposed victim, Amina Agisheff, who was not a prostitute, on dry land near Interstate 90; the second victim, Wendy Coffield, in the river; the third victim, Gisele Lovvorn, on dry land south of the airport (and not in a cluster); the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh victims (Debra Bonner, Marcia Chapman, Cynthia Hinds, and Opal Mills) in or near the river; and almost all of the rest, with the rather glaring exception of Carol Christensen, on dry land and in clusters.

This actually shows that a strong argument can be made that there are at least two distinct, discernible patterns to the murders: the dry-land killings, on one hand, and the water victims plus Christensen. Hers is the only case in which authorities claim to have a 100 percent DNA match with Ridgway.

The murder of Christensen in May 1983, in fact, was so far off the original Green River modus operandi that Reichert, then the lead investigator, didn’t want to include her on the official Green River victims list. She was only added when then-task force commander Frank Adamson insisted, and only because Christensen—who, like Agisheff, had no involvement in prostitution—was last seen on the Sea-Tac Strip where so many of the other women disappeared.

Adamson, who is now retired from the Sheriff’s Department, always insisted that the process of listing murdered women as Green River victims involved an arbitrary assessment and reflected a continuum of criteria. According to Adamson, one end of the continuum reflected the river victims, by definition the work of the “Green River Killer,” while the other end of the continuum was represented by Christensen, who, as many people now know, was found fully dressed and with a wine bottle among other props left by the killer. (In Keppel’s view, this was “humiliating.”)

As a result, the most striking aspect of the DNA case against Ridgway is that it represents the two extremes of the continuum—the river victims and Christensen. Some analysts see commonality among the victims Ridgway is formally accused of killing: a religious motif with water and wine, stones, fish and sausage, which were present at those various sites. But none of the murders Ridgway is charged with is consistent with the bulk of the uncharged counts, that is, those whose bodies were found on dry land and in clusters, and so far there are 37 of those. To this point, there is nothing to connect Ridgway with any of the other crime scenes, apart from accounts such as Miley’s, which only possibly place Ridgway in proximity of a victim at some point before they were killed. There are other, similar accounts that place Ridgway with victims who later turned up missing, namely Marie Malvar, Keli McGuiness, and Alma Smith. A triangular-shaped stone found at the site of Connie Naon’s body south of the airport, similar to those found with Chapman and Hinds, is unavailing. Sometimes a rock is just a rock.

What this means is that Ridgway’s defense team only needs to prove that he could not have committed the dry-land murders to raise doubts as to whether he killed anyone at all.

UNDER THESE circumstances, and with a case that might well be shaken to pieces by a vigorous defense, the issue of the prosecution’s refusal to plea bargain resurfaces. Assuming that Ridgway is responsible for the river victims and Carol Christensen—and the DNA evidence collected from those crime scenes seems very persuasive—what would tie Ridgway to the other 45, so-far uncharged crimes?

The clustering system so evident in the case now comes to work both for and against Ridgway. The argument here is that in placing the five victims in the river, a supposedly lone killer was following the same sort of clustering pattern found on dry land. In other words, with the exception of the water, it’s the same modus operandi. But that doesn’t prove that Ridgway is the one and only killer. Moreover, the clustering system of the dry-land murders shows another distinctive pattern: It appears that the dry-land killer first tested the security of a cluster by depositing an initial victim, then didn’t return to the area for a substantial period of time. If the victim wasn’t discovered, the perpetrator knew the area was safe from imminent discovery, and so he returned with numerous more dead women in fairly quick succession.

Contrast this with the river situation: The killer deposited the body of Wendy Coffield in the Green River on July 12, 1982, or so. The body was discovered three days later. Yet the river killer, assuming that the same person who killed Coffield also killed Bonner, Chapman, Hinds, and Mills, returned to the area less than two weeks later and after Coffield had been discovered. This doesn’t fit the pattern of caution seen in the dry-land murders.

There is more. Before her disappearance, Coffield was said to have been hanging out with Bonner and Chapman in Tacoma, which raises the possibility that Coffield’s killer might have been the same person who also killed Bonner and Chapman. That’s one reason the prosecutors want to include evidence from Coffield and Bonner in their case against Ridgway.

And yet, Coffield’s cousin, Leann Wilcox, was murdered six months earlier in Federal Way. That was then-detective Reichert’s first homicide case. Reichert has always insisted that Wilcox was not a Green River victim, even though she knew and worked with Coffield, Bonner, and Chapman. If DNA tests on fluids recovered from Wilcox’s body show Ridgway could not be her killer, that might indicate there is another killer involved in the murders—possibly someone known to Ridgway, in fact. If Ridgway’s DNA ties him to the river killings, the DNA found with Wilcox might lead the way to a Ridgway counterpart and the possible solution of the dry-land crimes.

FINALLY, BASED ON investigators’ valiant efforts to pinpoint where and when the 49 official Green River victims were last seen, it appears impossible for Ridgway to have committed all the murders by himself. For example, according to the police, victims Sandra Gabbert and Kimi Kai Pitsor were both last seen on the same day, April 17, 1983, at about the same time, but miles apart. And their skeletons were found in two widely separated places. If the police dates and times of disappearance are correct, it would have been logistically implausible for one person to have committed both murders.

A similar situation arises when one examines the last-seen dates and times for all 49 of the women. If the police data are correct, at least 18 of the women were taken on either the same or the day following another’s disappearance. This is powerfully suggestive of tandem killers, each egging the other on.

This is where a truthful statement from Ridgway would have been most helpful. By offering a life-without-parole plea bargain, prosecutors might have induced Ridgway to accept responsibility for those murders he might actually have committed, thereby clearing the decks for an intensive reinvestigation of the unclaimed crimes—and with Ridgway’s assistance. No such offer was ever made, according to the defense. Should evidence have emerged showing that Ridgway was involved in murders he did not confess to, there would have been no bar to seeking the death penalty for those crimes, thereby helping to ensure Ridgway’s candor.

In one important sense, one can sympathize with Maleng: As he has said repeatedly over the years, there are some crimes that simply demand the death penalty. As he once put it, “Jesus may have taught forgiveness, but he didn’t say you don’t have to pay the price.” The price of serial, random, so-called “recreational” murder in any civilized society ought to be the most severe sanction available, and in this state, that sanction happens to be death.

Maleng doesn’t want to be in the position of seeming to reward murderers for killing more, rather than fewer, victims. By agreeing to not seek the death penalty for Ridgway in return for his wholehearted, truthful, verifiable cooperation, Maleng has said, he would be sending a signal: The more you kill, the more we’ll deal. That’s why he rushed to the podium to give his we’ll-make-no-deals assertion so early in the game.

But there are larger issues at stake than just the conviction of one man, a possible multiple killer, however significant that might be. There is an issue of clarity— determining if the public-health problem of a wanton serial killer is really resolved. There is the issue of true finality for the dead women, and especially their families—true even more for those whose loved ones are still among the missing. And there is the issue of whether the community—which so courageously took this case on by assigning precious public resources to it at a time when it would have been so much easier to walk away, ignoring those who did not vote, like Paige Miley—ought to settle for a partial truth.

THE OFFICIAL VICTIMS

This list is organized by the eight clusters in which most of the bodies were found. Numbers indicate the probable order of disappearance, based on the reported date the person was last seen. Pacific Highway South is now called International Boulevard near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

A. GREEN RIVER CLUSTER

[2] WENDY LEE COFFIELD, 16. Last seen July 8, 1982, at a Department of Social and Health Services receiving home in Tacoma. Found on July 15, 1982, in the Green River in Kent.

[4] DEBRA LYNN BONNER, 23. Last seen July 25, 1982, at 27th Avenue South and South 216th Street, south of Sea-Tac Airport. Found Aug. 12, 1982, in the Green River in Kent.

[5] MARCIA FAYE CHAPMAN, 31. Last seen Aug. 1, 1982, near 30th Avenue South and South 188th Street. Found Aug. 15, 1982, in the Green River in Kent.

[6] CYNTHIA JEAN HINDS, 17. Last seen Aug. 11, 1982, at South 200th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found Aug. 15, 1982, in the Green River in Kent.

[7] OPAL CHARMAINE MILLS, 16. Last seen Aug. 12, 1982, at South 193rd Street and Pacific Highway South. Found Aug. 15, 1982, on the bank of the Green River in Kent, not far from Chapman and Hinds.

B. STAR LAKE ROAD CLUSTER

[8] TERRY RENE MILLIGAN, 16. Last seen Aug. 29, 1982, at South 144th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found April 1, 1984, at Star Lake Road in South King County.

[15] ALMA ANN SMITH, 18. Last seen March 3, 1983, at South 188th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found April 2, 1984, in the Star Lake area.

[16] DELORES LaVERNE WILLIAMS, 17. Last seen March 8, 1983, at South 188th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found March 31, 1984, in the Star Lake area.

[17] CARRIE A. ROIS, 15. Last seen March 18, 1983, in Seattle when she ran away from a receiving home. Found March 10, 1985, in the Star Lake area.

[18] GAIL LYNN MATHEWS, 24. Last seen April 8, 1983, Sea-Tac Airport. Found Sept. 18, 1983, in the Star Lake area.

[20] SANDRA KAY GABBERT, 17. Last seen April 17, 1983, at South 139th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found April 1, 1984, in the Star Lake area.

C. SOUTH AIRPORT CLUSTER

[10] MARY BRIDGET MEEHAN, 18. Last seen Sept. 15, 1982, at South 165th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found Nov. 13, 1983, at South 192nd Street and 27th Avenue South.

[19] ANDREA M. CHILDERS, 19. Last seen April 16, 1983. Found Oct. 11, 1989, in the 2700 block of South 192nd Street.

[26] CONSTANCE ELIZABETH NAON, 21. Last seen June 8, 1983, at South 188th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found Oct. 27, 1983, at South 191st Street and 25th Avenue South.

[28] KELLY MARIE WARE, 22. Last seen July 18, 1983, near 22nd Avenue and East Madison Street in Seattle. Found Oct. 29, 1983, near South 190th Street and 24th Avenue South.

D. MOUNTAIN VIEW CEMETERY CLUSTER

[21] KIMI-KAI PITSOR, 16. Last seen April 17, 1983, at Fifth Avenue and Blanchard Street in Seattle. Skull found Dec. 15, 1983, near Auburn’s Mountain View Cemetery. Rest of remains found Jan. 3-4, 1986, about 300 feet from where skull was found.

[ ] UNIDENTIFIED BONES. Found Dec. 31, 1985.

[ ] UNIDENTIFIED BONES. Found Jan. 2, 1986.

[ ] UNIDENTIFIED SKULL. Found January 22, 2002.

E. ENUMCLAW CLUSTER

[23] MARTINA THERESA AUTHORLEE, 18. Last seen May 22, 1983, near South 188th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found Nov. 14, 1984, 10 miles east of Enumclaw, about 20 yards south of state Route 410.

[30] DEBBIE MAY ABERNATHY, 16. Last seen Sept. 5, 1983, when she left her apartment to go to downtown Seattle. Found March 31, 1984, 12 miles east of Enumclaw, just south of Route 410.

[33] MARY SUE BELLO, 25. Last seen Oct. 11, 1983, leaving her grandparents’ home in Seattle, headed for the Sea-Tac Strip. Found Oct. 12, 1984, eight miles east of Enumclaw, just south of Route 410.

F. NORTH AIRPORT CLUSTER

[12] SHAWNDA LEEA SUMMERS, 17. Last seen Oct. 9, 1982, near Yesler Way in Seattle. Found Aug. 11, 1983, near South 146th Street.

[24] CHERYL LEE WIMS, 17. Last seen May 23, 1983, in Seattle. Found March 22, 1984, just north of Sea-Tac Airport near a baseball field.

[ ] UNIDENTIFIED BONES. Found March 21, 1984, at South 146th Street and 16th Avenue South.

G. INTERSTATE 90 CLUSTER

[1] AMINA AGISHEFF, 36. Last seen July 7, 1982, leaving a Seattle apartment. Found April 18, 1984, south of I-90 near North Bend.

[29] TINA MARIE THOMPSON, 22. Last seen July 25, 1983, leaving a motel along Pacific Highway South. Found April 20, 1984, at Southeast 104th Street and Route 18.

[32] MAUREEN SUE FEENEY, 19. Last seen Sept. 28, 1983, leaving her Seattle apartment. Found May 2, 1986, off I-90 near North Bend.

[34] DELISE LOUISE PLAGER, 22. Last seen Oct. 30, 1983, near 15th Avenue South and South Columbian Way in Seattle. Found Feb. 14, 1984, near Exit 38.

[35] KIM NELSON, 26. Last seen Nov. 1, 1983, near South 141st Street and Pacific Highway South. Found June 14, 1986, near Exit 38.

[36] LISA YATES, 26. Last seen Dec. 23, 1983, in Seattle’s Rainier Valley. Found March 13, 1984, near Exit 38.

H. OREGON CLUSTERS

[11] DENISE DARCEL BUSH, 22. Last seen Oct. 8, 1982, at South 144th Street and Pacific Highway South. Body apparently placed in a wooded area at South 137th Street and 144th Avenue South near Pacific Highway South in Tukwila. Skull found June 12, 1985, in Tigard, Ore.

[13] SHIRLEY MARIE SHERRILL, 18. Last seen between Oct. 20 and Nov. 7, 1982, in Seattle’s Chinatown. Found June 14, 1985, in Tigard, Ore.

[27] TAMMIE CHARLENE LILES, 16. Last seen June 9, 1983, at Third Avenue and Pine Street in Seattle. Found April 23, 1985, in Tualatin, Ore.

[ ] UNIDENTIFIED BONES. Found April 23, 1985, near Tualatin, Ore.

SINGLES

[3] GISELE LOVVORN, 17. Last seen in July 1982. Found in August 1982, near South 200th Street. Could be part of the south airport cluster.

[9] DEBRA LORRAINE ESTES, 15. Last seen Sept. 20, 1982, at a motel at Pacific Highway South and South 333rd Street. Found May 30, 1988, at South 348th Street and First Avenue South. Could be part of the south airport cluster.

[14] COLLEEN RENEE BROCKMAN. Last seen about Dec. 24, 1982. Found May 26, 1984, near Sumner in Pierce County. Could be part of the Mountain View Cemetery cluster.

[22] CAROL CHRISTENSEN, 29. Last seen May 3, 1983, at South 148th Street and Pacific Highway South. Found May 8, 1983, near Southeast 244th Street and the Maple Valley- Black Diamond Highway.

[25] YVONNE SHELLY ANTOSH, 19. Last seen May 31, 1983, leaving a motel near South 141st Street and Pacific Highway South. Found Oct. 15, 1983, at Southeast 316th Street and the Auburn-Black Diamond Road.

[31] TRACY ANN WINSTON, 19. Last seen Sept. 12, 1983, at Northgate Mall in Seattle. Portion of her remains found near Cottonwood Park in Kent, near the Green River, in 1989.

[37] MARY EXZETTA WEST, 16. Last seen Feb. 6, 1984, near Rainier Avenue South and South Ferdinand Street in Seattle. Found Sept. 8, 1985, in Seattle’s Seward Park.

[38] CINDY ANNE SMITH, 17. Last seen March 21, 1984, leaving home in South King County to hitchhike to a sister’s home in Seattle. Found June 27, 1987, off Route 18 near Green River Community College.

MISSING

These women are believed to be victims.

[ ] Kase Ann Lee, 16. Last seen Aug. 28, 1982, on Pacific Highway South near South 208th Street.

[ ] Rebecca Marrero, 20. Last seen Dec. 3, 1982, in West Seattle.

[ ] Marie Malvar, 18. Last seen April 30, 1983, on Pacific Highway South near South 216th Street.

[ ] Keli McGinness, 18. Last seen June 28, 1983, on Pacific Highway South.

[ ] April Buttram, 17. Last seen Aug. 18, 1983, in Seattle’s Rainier Valley.

[ ] Patricia Osborn, 19. Last seen Oct. 20, 1983, possibly in downtown Seattle.

[ ] Pammy Avent, 16. Last seen Oct. 26, 1983, possibly in the Rainier Valley.

Carlton Smith

Carlton Smith covered the Green River murders for The Seattle Times from 1983 to 1991. He is the co-author, with Tomas Guillen, of The Search for the Green River Killer (Penguin-Onyx, 1991). Since leaving The Seattle Times, Smith has written 14 other books about homicide, including five about serial-murder cases. As part of the research for this article, Smith reviewed his own files and the court filings in the Gary Ridgway case, and conducted interviews with a variety of people, including members of the Ridgway defense as the team viewed some of the crime scenes. Smith lives in San Francisco, where he is completing a book on accused Oregon family killer Christian Longo.