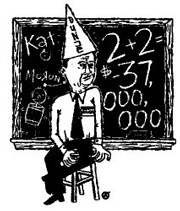

THE BLACK HOLE in the Seattle School District budget is worse than announced. Called a $33 million “shortfall” by Supt. Joseph Olchefske on Oct. 4, the district’s mind-boggling budget mistakes and flawed projections for the current and past school year now total $35.4 million. Narrowing the gap could require substantial additional money in financing costs. Some officials at the Stanford Center school-district headquarters predict the deficit and recovery tab will top $37 million once a district audit is completed. “We don’t yet know how deep a hole it is,” says one.

Many are still astonished that the district operated with such faulty controls and permitted corporate-style practices—balancing and closing the books by quietly shifting losses to the next year. In conversations with Seattle Weekly, some officials say the critical miscalculations, blamed principally on former chief financial officer Geri Lim, were part of a system that Olchefske allowed, despite criticism. A former investment banker, Olchefske has controlled the purse strings since coming to the district in 1995, at first as chief financial officer. In the time since, the district has racked up six straight critical audits by the state auditor. Though the reports are based on just a sampling of district programs, the state questioned hundreds of thousands of dollars in spending and losses.

State auditor Brian Sonntag repeatedly told the district that if it took care of its nickels and dimes, the dollars would take care of themselves. But the state says the district sometimes seemed disinterested in repairing its systems or helping auditors track down missing money. In a recent instance, district officials wouldn’t schedule a requested auditor’s interview with an employee, though the worker was suspected of being “overcompensated” by as much as $46,000 through forged time cards.

That reluctance, the lack of oversight and controls, and the apparent cover-up of the deficit has parents and others pressing Olchefske to resign. (Petition-gathering opponents are also now raising a variety of leadership issues as well). Judging by their e-mails, many were already incensed about a lack of oversight after Seattle Weekly quoted Lim’s reaction in August to the latest state audit. Asked how concerned she was about $70,000 in questioned funds, Lim suggested it wasn’t a major deal (see “Missing Money,” Sept. 5). “We have to weigh costs . . . of making sure all things run correctly vs. taking money out of the classroom,” she said.

AS WE NOW KNOW, Lim was at the time weighted with the bigger problems of the secret deficit, which she discovered in June 2001. A computer “information gap” allegedly led to a $7 million mistake and another $5 million in 2000-2001 debt had simply been shifted to the 2001-2002 budget. Lim kept that quiet, hoping it would smooth out—the school board unwittingly approved a budget with a $12 million hole in it. But the gap grew to $21.9 million by year’s end, due to other errors, overspending, and the economy. Last month, with the crisis certain to eventually leak out, the district confessed, saying the shortfall had also caused a $13.5 million (and counting) deficit for the current year, and that it will affect next year’s funding, too.

Olchefske says he knew nothing until August. That’s when Lim, a week after talking with Seattle Weekly, resigned, saying she needed more time to aid her ailing parents in Hawaii. Back then, chief operating officer Raj Manhas told Seattle Weekly that Lim did “wonderful” work. In a statement, Olchefske said she played a key role in improving fiscal and public credibility. Today, Olchefske, while accepting a share of responsibility, has fingered Lim as the mother of the deficit. (Lim has said little and couldn’t be reached for further comment.) The district says the money wasn’t misused and at least went toward fulfilling its mission to teach. But the district’s teaching/learning division will be hit hard by new deficit-caused cutbacks—about $6 million this year alone. The district hopes to make up some of its other losses by drawing on reserves, undercutting the district’s ability to respond to new crises and extending its loan costs. It plans to replenish those funds with the sale or lease of excess properties—although some are already dedicated to paying off the new $52.4 million Stanford Center. Actually, no one is certain yet how the tab will be paid, and the frustration is palpable. “Everybody,” says school board member Mary Bass, “really should be outraged.” Everybody, it seems, is.

‘I Made Mistakes’

One of the mysteries of Seattle School District finances has been the “financial improprieties” that caused popular middle-schools director Donna Hudson to lose her job in September. According to district officials, Hudson chose to resign in the middle of an ethics probe rather than face being fired for cashing her $5,185 district payroll check and claiming it had been stolen and forged, then obtaining a replacement check. Hudson, 49, who earned $108,000 annually, also ran up a $5,000 tab using a co-worker’s credit cards, officials say.

Documents from the case file state that Hudson signed a notarized affidavit to the district claiming her July 1 payroll check had been lost or destroyed. The district’s policy is generally to withhold a replacement check until an investigation is complete. But it issued a new check July 22 after Hudson offered her unused vacation time as collateral.

The district’s investigation began to turn up discrepancies. The first check had apparently been signed and cashed by Hudson, though she maintained it must have been forged. The district decided to withhold her August check as it probed further, causing Hudson to complain about a policy “that would assume the worse about [district] employees.”

She produced purported letters from the bank, dated July 2 and July 16, citing an “error” in her account that caused checks to bounce, including one to her landlord. Eventually, she turned over a copy of her bank account showing the deposit and offering to pay it back.

Documents show Hudson apparently got $1,500 cash back when she deposited the check July 1 and took a separate withdrawal of $2,500 from the check and/or other funds. After that she had $3 in the bank. By July 22, a dozen of Hudson’s personal checks had bounced and her account was overdrawn by $394. “She was having money problems, but we don’t know why,” a district official says.

In the course of the probe, officials also learned of Hudson’s apparently unauthorized use of a co-worker’s credit card for gifts and travel. She has settled that dispute by promising to repay the person. Hudson’s final paycheck—minus what she owed the district—was $544, which the district turned over to the former co-worker “in partial consideration” of Hudson’s $5,000 obligation to her.

The well-liked ex-administrator could not be reached for comment. But in a letter to the district, she says: “I made mistakes. I hope to repair my life in a manner of which I can be proud.”

Rick Anderson