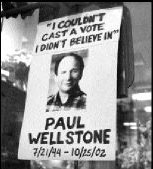

THE TRAGIC DEATH last week of Minnesota Sen. Paul Wellstone is convulsing liberals and progressives all out of proportion to Wellstone’s actual influence in the Senate. Wellstone had an unusual impact for a two-term senator from a midsized state, but in the end, he was only one senator of 100, one congressperson of 535.

To some left-of-center folks, however, he was far more, and the canonization got under way within hours of the plane crash. Every four years, progressives seem to anoint one or another hot name as their Democratic savior: Jesse Jackson. Jerry Brown. In the run-up to 2004, it’s Dennis Kucinich. And four years ago—before health problems nixed his exploration of a presidential candidacy—it was Wellstone. That cycle and years of national fund-raising based on his populist image have made Wellstone a well-known and (usually) loved figure in liberal circles.

This, along with a tight re-election bid that suddenly morphs into a crisis that could again swing control of the Senate, makes Wellstone’s death a particularly newsworthy national story. But there is another way, beyond his liberalism and the Democrats’ razor-thin Senate majority, in which Wellstone will be sorely missed. Wellstone himself identified it in an NPR interview last week, in a story that focused on his race this year against former St. Paul mayor Norm Coleman and Coleman’s characterization of Wellstone as out of step with the Senate. Coleman’s campaign has championed the notion that he would be a consensus builder who would “get things done.” In response, Wellstone said scornfully, that Coleman was all about getting 51 votes. Wellstone preferred to reserve the right to do what he believed was right, no matter who did or didn’t agree.

I ADMIRED WELLSTONE on some points, disagreed on others, and that’s the point. There were actually policy stances, consistent ones that I could identify and respond to. Members of Congress, like presidents, increasingly are poll driven; there are very few who are consistently willing to take unpopular stands. Two of the most notable, Cynthia McKinney and Bob Barr, both representatives of Georgia, were drummed out by faceless “moderates” in their own parties in September. Now Wellstone is gone. Not many remain. Republicans and Libertarians have Texas maverick Ron Paul; liberals and progressives have—well, in the Senate, nobody, really.

Wellstone will be missed precisely because of the party he leaves behind: a collection of poll-dependent, colorless pols who probably wouldn’t endorse motherhood unless it tested well in focus groups of probable voters. Obits this week usually noted that Wellstone was the only Democratic senator in a tough race this year who voted against Bush’s war proclamation, but that speaks more to the rest of his party—and the lack of competitive races in our incumbent-friendly system—than it does about Paul Wellstone’s legacy. The shock that greeted Sen. Patty Murray’s anti-war vote speaks to the same point; Maria Cantwell and especially Murray, Washington’s senators, have been prototypes for the new, timid Democrat of which Wellstone was the antithesis.

Next week’s election, in the tradition of off-year federal elections, should be a referendum on George W. Bush’s presidency, but public interest seems tepid because there’s so little identifiable opposition to rally behind. The Democrats’ across-the-board timidity in the face of Bush’s presidency has enraged much of that party’s constituency and left it, essentially, without representation in Washington. Likewise, conservatives’ timidity in the face of an assault on the Constitution and a militarily unsound invasion plan has a similar pedigree; if Ron Paul could stand on the House floor and reel off 35 reasons why invading Iraq was a bad idea, how telling was it that fewer than a dozen other Republicans could bring themselves to agree?

FOR MOST congresspeople, taking a righteous stand can never be justified, because it’s always too great a risk right now, there’s always too much at stake this time around. Wellstone was willing to be the “1” in a 99-1 vote, and that’s why people mourn him so. Politicians who can’t identify their own nonnegotiable core moral values shouldn’t be in high public office. Politicians who can identify those values but discard them at the drop of a hat shouldn’t be in office, either.

The entire Democratic party has constructed itself in recent years by trying to appeal to new swing voters, and by telling its past supporters: Be patient. Now’s not the time. The lesson for Wellstone’s colleagues, as they see the reaction to his passing and the disinterest in an election that will determine control of Congress, is short and simple: Life is short. Take risks. Be for something.