CIRCLE OF FIRE

Biringer Farm Bagley Wright Theater, 4:45—5:15 p.m. Mon., Sept. 2

CENTERCIRCLESPIN

Snoqualmie Room, 12:30 p.m., 2 p.m., 4 p.m., and 6 p.m. Fri., Aug. 30-Mon., Sept. 2

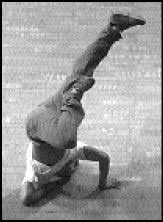

If you wanted to see it, you had to go to the street in the beginning. It has gone by several different names over its lifetime—breaking, b-boying, hip-hop, urban dance, street dance, break dance. Whatever you choose to call it, back in the early ’80s—on the streets of Brooklyn, perhaps, or in the Bronx—it involved watching young men spinning, twisting, and jumping as they invented a new glossary of movement.

Their dances were like their signatures, unique to themselves, a declaration of their personal style and a challenge to all comers. Combining elements of social dance, tap, and gymnastics, those youthful pioneers developed an intense kind of close-quarters dancing, often bounded by the edges of the cardboard or linoleum square they brought along as a floor. The basic structure was clarified, alternating between quick, bouncy footwork and virtuosic explosions, frequently upside down. The dancers would surround the performance space, with observers behind their circle, like traditional dances from around the world. As the group maintained a kind of rhythmic undercurrent, never really losing the beat, soloists would enter the middle to take the floor.

By the mid-’80s, this all had a name—break dancing—and was soon taken up as the “next big thing” in popular culture. After a quick series of increasingly unbelievable films (Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, anyone?) and broad media attention, the dance style was labeled a faded phenomenon and relegated to the list of the over-and-done-with (where the Lambada would soon join it). But instead of folding up and crawling away, b-boys and girls kept right on dancing, on the streets and in the clubs, forging a tight relationship with the MCs running events and music producers. A complex subculture was developing outside standard dance venues, with extensive competitions and appearances at concerts, so that the style most dancers thought was over began to make itself known again.

Today hip-hop dance is back with a vengeance—music videos, concerts, and clubs, even concert dance, where it’s been combined with everything from modern and tap to ballet. As the style has moved from the street to the stage, though, it’s had to accommodate the picture-frame organization of the theater, to open up the circle and show the audience what’s inside. Different artists have solved this puzzle in different ways: some taking the movement itself and using it like any other vocabulary; some more intent on re-creating the group experience and structures; some making a theater out of the street, staging competitions in big arena spaces like the gladiatorial battles they are.

We’ll see a bit of everything at Bumbershoot. The ongoing CenterCircleSpin brings the street to the Seattle Center grounds, staging a traditional battle for all comers. When local crew Circle of Fire performs in the Bagley Wright Theater, however, they’re trying for a middle ground, keeping the integrity of their dancing in a formal environment. The constant in all of this remains the dynamism of the movement, the commitment to rhythm, and, above all, a fine disdain for what other people might call it.