DRAWINGS PLEASANT & UNPLEASANT

Elliott Bay Cafe, 101 S. Main, 682-6664 7 a.m.-9 p.m. Mon.-Fri.; 9 a.m.-9 p.m. Sat.; 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Sun. ends Sat., Aug. 31

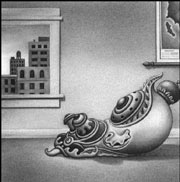

Jim Woodring’s charcoal drawings aren’t exactly well suited to a dining establishment like the Elliott Bay Cafe. His subjects include a toothed jellyfish hat, a fork-bodied slug thing holding a scaly scepter, and—in a grotesque reversal of the birth process—an oozing, multiappendaged sea creature ingesting an obese man (title: Afternoon). Not exactly the kind of thing you want staring down at you while chewing your ham sandwich.

Unappetizing as they may be, Woodring’s images are compelling, as even nonfans like me must admit. They get under your skin and change the way you see things. After several days of immersing myself in his drawings and comics, I found that everyday objects, such as my daughter’s rubber bath toy, began to glow with an obscure malevolence. Woodring’s pictures are effective in part because the artist is steeped in comics and animation history and speaks to us in a familiar visual vocabulary of stylized critters. Creepy subversion of the cute may by now be a standard trick, but in Woodring’s hands it becomes something extraordinary. He is able to communicate a profound yuckiness that is all his own.

What’s disappointing is that Woodring doesn’t choose to refine his tremendous rush of terrible images into some greater whole. He seems content instead to be a master of the fragment.

Woodring got into cartooning as he was recovering from years of alcoholism. His early work, published by alternative L.A. newspapers, was competent enough to land him stints at both Disney and Hanna-Barbera. The success of Jim #1, published by Fantagraphics Books, allowed Woodring to quit his day job in 1987, when he moved to Seattle. Woodring has not had any major gallery shows, but in the circles in which he is known, he is held in awe, and he attracts uniformly reverential prose in comics journals and other alternative venues. He counts among his fans Laurie Anderson and guitarist Bill Frisell, with whom he recently collaborated on Mysterio Simpatico, a multimedia performance that played in New York and Seattle. In perhaps the ultimate tribute, his work appeared in the background of the comic book store on The Simpsons earlier this year.

According to the account on his own Web site (www.jimwoodring.com), Woodring’s imagery originates partly in the delusions and apparitions that tormented him in childhood. He believed his parents were planning to murder him in his sleep and suffered from what he describes as “waking nightmares.” The artist’s raw material is his great strength, but also his limitation. While he is undoubtedly successful at imparting his childhood feelings, he is unwilling to go beyond these momentary flashes of horror to craft something of greater substance. The goal seems to be to present the material he dredges up from Jungian depths unmediated by conscious artistic choice. He has described the ideal creative process as “meat falling off a bone.”

In the introduction to The Book of Jim, a compilation of his comics, Woodring wrote, “I grew up believing that horror is not only fun, but sacred. Horror for me was a divine emotion which accompanied the reception of oracular tidings.” But in his work, the tidings never arrive, the mystery is never solved. There is nothing more than the immediate emotion produced by the images; it’s all pathos, no ethos.

Even judged by the limited goal of producing a sensation of horror, the charcoal drawings in the current exhibit are less successful than Woodring’s work on the printed page. Seeing the drawings in person adds exactly nothing to seeing them in reproduction. Woodring has great facility with charcoal, creating volume and weight with meticulously executed shades of gray, but his drawings have a fussy, labored quality. Unlike some of his comics, which have a warm funkiness reminiscent of Robert Crumb, these drawings are choked with a brittle virtuosity. (Nine of the drawings were used in Mysterio Simpatico.)

Though often described as “whimsical,” the drawings look to me like the product of a control freak. Looking at them, you are not exactly riding the winds of fancy—it’s more like being shot along a track into a house of horrors. Woodring’s quest to capture a particular dreamlike atmosphere leaves no room for the play of the viewer’s own imagination. His work has no greater resonance beyond its immediate (admittedly powerful) effect. It leaves me longing for old-fashioned virtues like humanity and a broader perspective on the world that incorporates dreams but is not comprised solely of them.

What is behind Woodring’s visions? He is apparently too committed to mystery for its own sake to ever seriously pursue the question. And he obviously relishes the effect his art has of short- circuiting rational analysis. In The Book of Jim, he tells the story of how two psychologists in succession refused to treat him after seeing his art. But I’ve got my own ideas. If I were his analyst, I’d wave my pipe in the air and tell him, “Just draw your mother’s vagina and get it over with! Then you can show us what you can really do.”