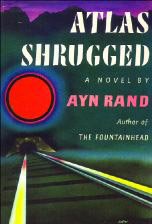

TWELVE

by Nick McDonell

(Grove/Atlantic, $23)

Zeitgeist Art & Coffee, 171 S. Jackson,

624-6600; 7:30 p.m. Wed., July 31

Nick McDonell is very young and will soon be very famous. His segment on The Today Show went well. He’s been extolled in The New York Times and compared to Bret Easton Ellis. Hunter S. Thompson says, “Nick McDonell is the real thing.”

Since his debut novel was published three weeks ago, the story in Twelve has come to be overshadowed by the story of Nick McDonell.

Whatever Thompson means about McDonell being the “real thing,” that can’t be the most apt way to describe a writer who, weeks in advance of Twelve‘s publication, apparently misled The New Yorker. The 18-year-old author told a New Yorker reporter that Details had asked him to remove his shirt when he posed for a photo, but he refused. “Nobody from Details ever asked him to disrobe,” the editor of Details shot back in a letter The New Yorker printed the following week. “We don’t know much about his writing,” the letter went on, “but he seems to have an extremely productive imagination.”

What McDonell meant to say—the message was clear, though he stumbled over its execution—was that too much attention is being paid to his boyishness and not enough to his book. The fact that everyone’s making so much of the book because of his age seems lost on him.

The main character in Twelve is a teenage drug dealer named White Mike who doesn’t drink and never does drugs. This is supposed to amaze and endear you to him, but it’s implausible, so it doesn’t. How does someone who’s never so much as tried drugs find himself with the connections to become a dealer? Holes like that are everywhere in Twelve.

White Mike has pale skin and no close friends. He is thoughtful and lonely, an interloper at parties, an outsider on the inside. In many ways, he is Nick McDonell—they both intellectualize things; they are both observers. McDonell is a precocious novelist; White Mike, we come to learn, is a genius.

Not so genius, though, is McDonell’s decision to employ White Mike—the only character developed with acuity and a measure of depth—as a device: an iconoclast among his peers, the only teenager in the book not thoroughly consumed with drugs and fucking. Thus, McDonell unwittingly perpetuates the idea that drugs and sex overwhelm every other aspect of teenage American life. That perception is a commonplace of our culture; it’s also a clich頡nd untrue. A more honest young author might expose this new myth. Teenagers care more vigorously about poetry and music than most adults, and when I was in high school (four years ago), more of my friends were scared of having sex than were having it.

The standard rap on this book is that a prodigy has captured the experience of his generation, but McDonell hasn’t captured anything—he’s merely thrust the generic characterization of young people onto a new generation. He portrays girls who wear FUBU and get nose jobs for their birthdays, boys who suck down “doobies” and talk “mad smack” and aspire to be “niggas.” Reviewers and other writers eager to be perceived as vital and in touch and “getting it” applaud his work.

To McDonell’s credit, the language in his book is fresh and intelligent. He moves at a remarkable pace. If, at times, it progresses like a movie—chapters are rarely more than two pages, each one complicated and predominantly visual—the fractured story lines do for the most part come together rewardingly, if you can follow them.

McDonell, clearly informed by nonlinear cinematic postmodernism, sat down to write an ambitious novel. He confined the action to the course of just five days leading up to a raucous—and disastrous—New Year’s Eve party. (What these characters manage to pack into five days, you wouldn’t believe.) What he achieved is a narrative velocity that builds like a quickening bullet—and that makes sudden impact, and stops short, in the last few words. His characters are funny and lonely and charged with a terrifying, intractable anger. Even if you end up feeling manipulated, you will appreciate McDonell’s attempt to get at deeper issues than he had ever let on.

Courage is required of any person who sits down to write a novel this focused and fierce—no matter their age—and with the publication of Twelve, McDonell has proven that he has more courage than most. He will get better.