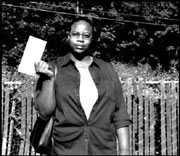

Two weeks ago, Latoya Smith, a 30-year-old mother of two, met with her welfare caseworker, who sternly reminded her that she had eaten up considerable time on her welfare clock. “She let me know I had used up 40 months, that 60 months was all we were going to get, and that the best thing I could do was get off [welfare] and get a job,” Smith recalls, taking a break from a job-hunting class outside the Rainier Valley welfare office.

Two fellow welfare moms taking a break with her, Tianna Hicks and Lisa Williams, have received similar reminders over the past few weeks about their time on public assistance (27 and 53 months, respectively), in the form of letters from the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS).

All of this would make sense except for one thing: In the words of Chet Linowski, deputy regional director for DSHS in King County, “the five-year limit, as it was, no longer exists.” And no one at all is being cut off completely from public benefits.

You would think this news would be getting out now that the five-year anniversary of state welfare reform is around the corner—Aug. 1. That was when a beginning group of long-term recipients was supposed to be kicked off. Strangely, the change has attracted little notice or controversy.

Even welfare recipients aren’t being told. “What we’re seeing is caseworkers not giving people information and still trying to scare people with time limits,” says Megan Donahue, an advocate with the Welfare Rights Organizing Coalition. DSHS responds that it sent letters in June explaining the new policy, though they would seem to be contradicted by subsequent communication to some clients.

The turnabout in policy happened in November, when Gov. Gary Locke utilized his prerogative under federal law to set rules for who could be exempted from the clock.

As expected, Locke offered a reprieve for those who are disabled, those taking care of disabled or vulnerable relatives, and older folks looking after kids. Locke gave them a permanent exemption from the time limit. Equally important, he relieved them from participation in the arduous WorkFirst system, a series of caseworker meetings, job readiness workshops, job-hunting requirements, and constant documentation that can be a perpetual struggle for people having a hard time just making it through the day.

The governor then went further by saying that anyone who is “playing by the rules,” that is, satisfactorily participating in the WorkFirst system, can also continue to get benefits indefinitely. His thinking was to remove the “arbitrary” nature of the time limit, according to Ken Miller, the governor’s top welfare adviser.

More generous still, Locke determined that even those who weren’t playing by the rules would still receive money, albeit a reduced amount that wouldn’t actually go to them. Instead, it will go to a “protective payee,” an entity empowered to use it only for basic living expenses like rent and utilities as well as approved needs of children. This system kicks in at the five-year mark.

“The governor didn’t want to cut off assistance to children; on the other hand, he wanted to make clear that something would happen,” Miller explains.

The Legislature, when it went into session that winter, let Locke’s plan ride without serious debate. In a somber climate forged by Sept. 11 and the recession, state legislators were preoccupied with the budget and transportation. Conservatives who might be expected to protest seem to have been pleased enough with the mileage already achieved from welfare reform not to bother haggling over the revisions. “A lot of us have bragged about that bill,” says archconservative Sen. Harold Hochstatter, R-Moses Lake, referring to the original welfare reform bill. “We figure at least it’s gone in the right direction.” In any case, the governor’s plan is in line with what a lot of states around the country have done.

Further deflecting controversy, DSHS avoids explaining the new leniency in a direct way. Linowski, of the King County office, may declare that the five-year limit of old is no more and that any caseworkers who say otherwise are doing so “incorrectly and illegally.” But DSHS rules continue to say that there is a five-year limit. You have to read on to discover that “exemptions” and “extensions” are available on a renewable basis, and it’s almost impossible to discern from the literature that benefits could be paid indefinitely.

This is surely not just a question of confusing bureaucratese. State officials are leery of taking the pressure off welfare recipients to find jobs. Miller, of the governor’s office, says, “We were concerned that the message would be, ‘Look, we didn’t mean it after all.’ “

Accordingly, in addition to being indirect with its language, the state has toughened requirements for WorkFirst participation. As of next month, welfare recipients will have to job hunt or engage in related activities close to full time. Until now, they could do so for as little as 24 hours a week. What’s more, many people will be required to check in at a DSHS or an Employment Security office every day. Welfare advocates worry that the stringent rules will be tough to abide by, putting more people into the not-playing-by-the-rules category.

That’s a valid fear, given the results of a pilot implementation of the new program at the Kent welfare office. Mike Morris, the administrator there, says that while he’s getting more job placements from the program, he’s also having to sanction more people by reducing their money. Before the program went into effect in March, the office was sanctioning 50 people. Afterward, the number jumped to 200 but has gone down to 120 as people have adjusted to the new program.

Congress, currently debating bills on the next phase of welfare reform, may add more requirements yet.

The women taking their break at the Rainier Valley welfare office are, however, much more relieved than alarmed by the new system. “So you can keep getting money as long as you’re playing by the rules,” repeats Latoya Smith, marveling at this unexpected piece of news. “OK, sounds good.”

nshapiro@seattleweekly.come

Good News

Every now and then, Dolores Wilson takes her 10-year-old son, Eddie, out to a sit-down dinner at someplace like Red Robin or Azteca. It may not sound like much, but to Wilson, whose life in recent years has been consumed by looking after her other son, a profoundly disabled 7-year-old named Joshua, it’s sheer luxury.

Wilson has gotten a series of breaks since Seattle Weekly wrote about her struggle with welfare reform last fall. [“Does This Family Deserve Welfare?” Oct. 4, 2001] Then, she had spent four years trying to comply with welfare’s new demanding regulations while caring for a son who couldn’t speak or use the bathroom, who roamed around constantly creating chaos, and who liked to strip naked at every opportunity. The welfare workers handling Wilson’s case had come to the conclusion that she needed public assistance indefinitely, not just for the five years then allowed.

Now Gov. Gary Locke has permanently exempted people like her from the welfare time clock. As it happens, however, Wilson got herself off welfare last December.

She says she worked up the nerve to ask the Seattle School District for a job looking after Joshua on his bus rides to and from school—a job usually done by a nurse but which the district was having trouble filling. The district agreed. “I got myself a good wage, too,” Wilson says—$15 an hour for 20 hours a week (the hours include the time Wilson spends in school waiting for Joshua to finish).

That’s doubled Wilson’s monthly income from when she was on welfare, allowing her treats like dinners out. She now has time to spend with just her older son, because she finally found a reliable respite worker—a college friend with whom she had studied childhood education—to look after Joshua. Paid by the state, the friend comes three or four days a week, for four- or five-hour stretches. Previously, Wilson could measure her leisure time in seconds.

“I feel a lot better about my situation,” Wilson says. Even so, she’s glad welfare will be there if she needs it. “I might have to fall back on that,even though I’m trying really hard not to.”N.S.