With the recent release of Heathen, his latest dip into a pool of prescient lyrics and dramatic melody, David Bowie walked out the front door of self-publicity and wound up in the smudgy, aged hell Mick Jagger wakes up in every day of his tiny, ugly touring life. The one where, no matter how relevant your new music is, all is put asunder to sweat to the oldies. Three incidents surrounding Heathen‘s promotion should have scared Bowie worse than his Andy Warhol wigs in Basquiat did the filmgoing public.

1. On the day Heathen debuted, a BowieNet show at New York City’s Roseland drew a glut of spandex-wearing housewives. That these ladies chanted along to “Warsawa” was no consolation.

2. As he sang on a Manhattan street for The Today Show, a woman held up a sign bearing a Labyrinth-visaged Bowie from the Jim Henson movie of the same name. Underneath, it read, “I NAMED MY DOG JARETH,” after Bowie’s Muppet king in the film.

3. Joining past guests such as Michael Bolton, Barry Manilow, and Kenny Loggins, Bowie appeared on A&E’s Live By Request. Amiably facing the numbest of hosts (Mark McKuen), Bowie smilingly fielded phone calls from longtime fans and their children requesting “Ziggy” and “Starman” as if they were asking Santa for toys.

That Heathen is Bowie’s finest work in more than two decades won’t matter to many fans, at least not to the folks who yearn for glam’s stammering (but hardly steamy) past. The cold sexuality of glam, despite its Quaalude-fueled hedonism, felt as flashy as it looked. Truth was, no one wanted to smear their makeup. These aging acolytes are looking to Glitter Grandpappy Bowie like Calgon, to wash away the years and transport them back to a sexier, savvier, self-assuredly pouting past. (One where cellulite and stretch marks didn’t meet would be a nice start.)

It’s to Bowie’s credit that he’s still making crucial new music. Though he retreaded catalog material with his Sound + Vision tour and sold tunes like stock options, he’s never come off as an oldies acts. (Then again, seeing him warble “Space Oddity” with Adam Sandler for the latter’s new movie, Mr. Deeds, doesn’t help that argument.)

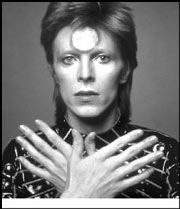

Amid publicity for Heathen, the concepts of age, sex, and fashion form a nexus of sorts for Bowie, his fans, and critics as his earliest, most famed creation peeks a henna-head from his crammed closet: Ziggy Stardust.

Marking the album’s 30th anniversary, EMI offers a dashing new two-CD set of The Rise and Fall Of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders of Mars, complete with outtakes, demos, and never-before-seen pics. Coinciding with this is the publication of photographer Mick Rock’s book Moonage Daydream: The Life and Times of Ziggy Stardust. The appearance of both is auspicious, despite—or perhaps because of—Bowie’s apparent disinterest in publicizing either.

Of course, Bowie’s had little use for Ziggy since discarding him in front of documentarian D.A. Pennebaker’s jittery cameras back in 1973. In a recent interview, Bowie seemed ambivalent— dismissive, touched, and even surprised—that people are still interested in his Zig-creation of liberation.

“I have incredibly fond feelings for that project and that particular time,” he said, taking a long pause. “Maybe I just can’t get excited about it right now—despite it being 30 years—because it’s only time that somehow makes it . . . bigger in people’s minds.”

Perhaps what confounds Bowie most is that Ziggy doesn’t seem to need him anymore either.

Recent cinematic escapades prove Bowie’s martian king/queen of androgyny lasted long enough to influence young filmmakers to create their own pansexual rock works. Pictures like Velvet Goldmine and Hedwig and the Angry Inch are literal—and perhaps more fully realized—retellings of the Ziggy myth: Hope to God you’re an alien baby, live fast, define your own sexuality, die young—but don’t really die, just transmogrify.

Androgyny was Ziggy’s first calling card. Not since Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel had pop culture witnessed such a facile flow of sexual identification complication. After that, add some theatrically Artaudian bloodlust, some Brechtian pragmatism, a little Rilke—all combined with Bowie’s heady musical mix of Little-Richard-meets-Dylan-meets-the-Velvets—and audiences back in 1972, including 10-year-old me, were set to follow.

Like Ian Fleming’s James Bond, Ziggy has a life of his own, apart from Bowie. Without smothering its maker, a cult of personality built up around this singular character, far beyond the intentions of its initial phase. Ziggy, like Bond, is independent: No matter what else his master does, Ziggy has never remained chained to his boss’ call for starshine.

The entirety of rock, from punk to new wave and beyond, has taken its cues from the fashion and fussy sounds of Ziggy. The iconic spike of feathered hair (conceived by Bowie, then-missus Angie, and Brit hairdresser Susie Fussey), the dyed-color wrestling boots, and flashy femme-jumpsuits can be seen across the pop panoply—from chart queen Pink’s coiffure, to rapper Eve’s look, to everything electroclashers Fischerspooner do.

Ziggy ushered in fashion flamboyance at a time when kids were, in the post-Woodstock era, sadly all about blue jeans and slack hair. Ziggy made clothing, makeup, and flash—personal style, really—accessible to girls and boys (and boygirls and girlboys) by making costumes colorful and lean. All of it achieved through keen calculation and high levels of sophistication and awareness; a merger of Japanese kabuki, American rock ‘n’ roll, and European theater into one.

More importantly, he preyed on an audience who, like Ziggy himself, were outcasts. Look back at fan footage from the era: Few of us were anything more than mawkish children with poorly applied rouge and clumped mascara atop pimply faces and chunky bodies.

Ziggy/Bowie knew this. He told us we were “beautiful” and “wonderful” and to give him our hands. Despite his innate nihilism, he would take us off to space with him in Christlike fashion.

So obviously then, Ziggy wasn’t just about the outfits. He was about fine- tuning and turning your life around, making you yours; anyway you wanted to be.

After Ziggy you no longer had to walk a straight line, literally or figuratively. Ziggy/Bowie gave his children—these tigers on Vaseline—a way to be radical in their approach to life, sexuality, and dress. Before Ziggy, said Bowie, “the idea of self invention, or reinvention, whatever, hadn’t ever really been postulated by anybody before.”

For some, it’s Bowie/Ziggy upon whom they hang the mantle of gay liberationist. Yet, that’s one of his greatest canards. For Bowie, all politics is personal. He’s never written an explicit protest song. And though there’s enough anthem and feyness on Ziggy to sink a cruise-ship dinner-theater version of The Boyfriend, Bowie didn’t intend to empower people to rise up. As it stands, he’s never marched for any cause but his own—not gay rights not flower power. The same then is true of Ziggy. The effect on audience lifestyle was gleaned merely by following Bowie’s example, not his powers of uplift/uprise. In fact, neither Bowie nor Ziggy—to the righteously queer men and women I knew back-in-the-day—were gay icons. Yet, I heard other straight men repeat one phrase over and over: If they had to sleep with one guy, it would be Bowie.

No gay man I knew ever said that. Bowie’s freakish femininity warded off most gay men, except those who were identifiably camp. As Bowie stated in “The Prettiest Star,” his sexuality was a “cold fire.” His Ziggy may have gnawed on Mick Ronson’s strings in that famous fellatio captured by Mick Rock. But he never swallowed. He just sort of devoured Ronson’s guitar.

Yet, Ziggy inspired genuine social change by altering how audiences and artists responded to rock, clothing, and sexuality. Neither the pens of Dylan nor Lennon, nor the swagger of Jagger nor the supple roar of Marvin, ever really did that.

Bowie continually and constantly reinvented himself and everyone followed. When Ziggy couldn’t keep up, Bowie destroyed him in a rock ‘n’ roll suicide, leaving little but brittle memory, big changes, and surprisingly innocent music.

George Martin, Brian Wilson, and Phil Spector made rock ‘n’ roll in gracious Technicolor and elegant Cinemascope. Bowie—as if Noel Coward in a leather bar—made it graceful without losing its sizzling heft. Credit Mick Ronson for the razor burn. Yet for all its bristling guitar, Ziggy was always a gently twee rock record. It’s never been my favorite Bowie album. Not as hedonistic or ferocious as The Man Who Sold the World, not as brightly beautiful as Hunky Dory, not as spectral and funky as Diamond Dogs, nor as elegiac as his Low/Heroes/Lodger/Scary Monsters quartet. It is, gently, in between all that.

Yet hearing Ronson’s riffs and Bowie’s oxygenated bitchy squeal—that tenor-to-alto leaping fleece of a voice— remastered for maximum volume, it all becomes clear once again. Dig the tart demo of “Sweet Head,” the preachy servitude of “Moonage Daydream,” the salacious cabaret of “Lady Starman,” and the apocalyptic message of “Five Years.” These are the things that made me want to be a Bowiekid in the first place. Death. Sex. Salvation. Theater. High cheekbones. Laughing gnomes.

I’m sure knowing that Ziggy gets audiences all misty and nostalgic—a kind of cornball sentiment—is the thing, deep in Bowie’s Heathen-istic mind, that he fears most.

But I bet Ziggy would love the drama.