ON AN UNSEASONABLY cold Tuesday night last week, in the pale-green basement of the Grace Apostolic Temple on Martin Luther King Jr. Way, hundreds of people crowded together to talk about Sound Transit’s plans to take their property and businesses for its proposed light-rail line through the Rainier Valley. The room, flanked on three sides by a stiff phalanx of suited, smiling Sound Transit staffers, was filled with a cacophony of voices asking similar questions in eight languages (including Vietnamese, Mandarin, and Cambodian): What’s going to happen to my property? When will we know? How much will I be paid? Can I have a lawyer?

But before any of those questions could be answered, there were egg rolls, fried rice, noodles, and fried chicken to consume.

A smiling King County Executive Ron Sims presided over the multiethnic feast (provided by Martin Luther King Restaurant), encouraging attendees to “eat, and take some home with you.” The message got through to some—although others, eager to find out the fate of their properties, were clearly in no mood to nosh.

Welcome to Sound Transit’s latest public relations nightmare. Over the next 12-18 months, the transit agency plans to begin purchasing all or a part of some 300 properties for its troubled 14-mile, $2 billion light-rail line from Seattle to SeaTac. Many of the purchases will impact struggling immigrant-owned businesses in the Rainier Valley.

Before the meeting, Sims, the new chair of Sound Transit’s board and a resident of the Valley since 1971, said he wanted to talk to property owners and tenants face-to-face before the agency started buying properties. “Sound Transit was going to send letters notifying property owners that we’re going to move to the acquisition stage, and I said, ‘We’re not going to do that. We don’t do things that way anymore,'” Sims said.

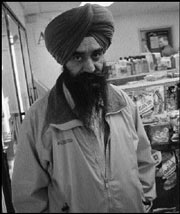

Sims’ assurances didn’t do much to impress folks like Gurdev Singh Mann, who came to the meeting hoping to find out what would happen to his gas station, a large, brightly lit Union 76 at MLK Way and Graham. Gurdev and his wife, who moved here from India with their two children, spent their life savings on the franchise, which cost them $450,000. Now, because Mann doesn’t own the property his station sits on, he worries that he could lose it all. “When we bought the station, we didn’t know what was going on. Every penny we have, we spend to pay off our loan,” Mann says. Mann says he and his wife spent another $85,000 to expand the station into “a nice store with a good location and a good clientele, [where] all the customers know me by name.”

LIKE MOST OF those who spoke at Tuesday’s meeting, Mann doesn’t want to be uprooted by light rail, which would run directly in front of his business. As a tenant, Mann is in a particularly unstable situation; he won’t get compensated until property owners, like the gas company that owns the land his station sits on, get their dip into the till. “There’s a lot like me who don’t own the property, but they have a business and are making a good living,” he says. “It’s hard to start from A, B, C again.”

If he thought it would do any good, Mann says, he’d tell Sound Transit exactly that. “I think it’s worthless to talk to these people,” he says. “There’s nothing written down—it’s always, later on, later on,” he says.

That was a common refrain during the meeting, as Sound Transit executive director Joni Earle, Sims, and agency staffers scrambled to answer questions about individual properties and bounced queries from one staff person to another.

Access—customers’ ability to get into businesses that remain open, both during construction, which is slated to start in 2004, and afterward—is another crucial concern for businesses. Properties slated as “partial takes,” as well as those scheduled to be partly blocked or closed during construction, could lose business as traffic—and customers—move to other avenues. Mann worries that if Sound Transit blocks access to his gas station, the car traffic that fuels his business could migrate to nearby arterials. “With all this construction, there will be no business,” he contends. But Sound Transit spokesperson Lee Somerstein said the agency has promised to do everything it can to avoid blocking businesses, and will only shut off lanes for 1,000 feet at a time.

Mann’s concerns are echoed by another MLK Way business owner, David Tran, whose printing shop at the corner of MLK Way and Henderson sits in the path of Sound Transit’s planned Henderson Street light-rail terminal. Like Mann, Tran leases the 3,000 square feet he needs to run his print shop, subletting another 1,700 square feet to a furniture store. And like Mann, Tran says he relies heavily on neighborhood drive-by traffic. He moved his business to the Rainier Valley from Kent—at an estimated cost of $10,000—because he wanted to serve the Asian community. “I’d rather close my shop than move out of this area,” Tran says. But he worries he may have no choice; already, Tran says, landlords have started raising their rents in anticipation of the increased demand. “Light rail will force everybody out of this area—they know people are going to look for space to move their shops, so everything in this area has gone up [in price],” Tran says.

If he does have to move, Tran says, the sooner Sound Transit lets him know when—and how much he can expect to get—the better. “They know we’ve got no choice, because they’re the government, and if they say we have to move, we have to move,” Tran says. “We have to just accept it and ensure that they pay us quickly and let us know quickly, so we can go and look for other properties.”

Tran and other business owners got at least a partial answer to those questions at Tuesday’s meeting, when Earl informed them that Sound Transit would start buying properties in the next year to 18 months. The agency is also offering to pay for independent appraisals on the 300-plus properties it plans to acquire in whole or part over the next few years. But that won’t do much to help folks like Mann, who worries that everything he’s worked for years to acquire may be crushed by Sound Transit’s bulldozers. “I was really enjoying my life. I love where I’m living, my kids are studying hard, and we want to send them to good universities,” Mann says. “Now I don’t know if we’ll be able to do that.”