JITNEY

Seattle Center, Seattle Repertory, 443-2222, $10-$44 Previews begin Wed., Jan. 23 7:30 p.m. Tues.-Sun.; 2 p.m. matinees Sat.-Sun. runs Mon., Jan. 28-Sat., Feb. 23

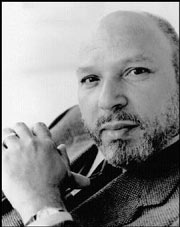

AUGUST WILSON tells stories. He likes to talk, and the real desire to connect that accompanies his intellect makes you want to listen—it’s certainly one of the reasons the playwright is a two-time Pulitzer winner (for Fences and The Piano Lesson). Over a series of eight works, he’s told the tale of what it meant to be black and American in the 20th century in nearly every decade, up through the ’80s milieu of King Hedley II. He recently refurbished his first play, 1979’s Jitney, about the valiant struggles of a community of men working for an unlicensed taxi company in Pittsburgh. The piece comes to the Rep, long an artistic home for the Seattle resident, in its new form this week, true to its young heart but polished by his constantly evolving art.

Seattle Weekly: How much do you see your craft as having changed?

August Wilson: I’m a much more confident playwright. Confidence is very, very important; it does something to you. I think this is one of the things, for instance, that Muhammad Ali carried into the ring with him, you know? He was scared every time he went in—you know, anything can happen. But he was confident in his skills, and it was the confidence that allowed him to rise to a certain level of performance. So when you sit down and write, if you have that confidence, you [have] a systematic way of going out and executing it.

What were your first thoughts on re-examining something you’d written so long ago?

I thought it was a pretty solid play. Of course, one of the actors came up to me [after the first new reading in 1996] and said, “Man, they ain’t gonna know this is your play.” And I said, “What you talkin’ ’bout?” And he said, “Ain’t got no monologues in it.” And I said, “I’ll have one for you tomorrow.” But that was one of those things—it didn’t have the monologues like my other work had. So I wrote him a monologue that night and then went back and wrote some monologues for the other characters, and then it began to take on a shape. But I didn’t want to destroy what it was, you know? If I were to write that play today, [it] would be totally different. So I wanted to preserve it as my first play, but enhance it with the stuff I had learned in the interim.

Was it hard to go back over it because your technique had changed?

Well, yeah, I was a better playwright by the time I went back to it. And it was just hard getting into the emotional heat of the moment, and I felt like it was already written and everything was set. I couldn’t get in, you know? We did the production in Pittsburgh, and [then] we were up in Boston, and I told [director] Marion McClinton, “Man, I feel like I’m in a box.” And Marion said, “Well, it’s your box.” And that was liberating. I thought, “Oh, it is my box—I can break it if I want.”

Toni Morrison was being interviewed by Charlie Rose a while back and he very ingenuously asked her if she was ever going to write something that did not deal with the black experience. Do you still, even this late in the game, have to confront people who somehow count your subject matter as lesser?

Oh, sure, yeah. For instance, after I wrote The Piano Lesson, they’d go, “Mr. Wilson, now that you’ve written these plays and exhausted the black experience, what are you going to write about next?” Well, maybe I’ll contribute to the thousands of books, plays, puppet shows, operas, and whatever about the white experience. Shucks, four plays and [the black experience] is done.

You’ve called writing a “remaking of the self.” Do you mean personally, professionally . . . ?

As a person, you evolve, your beliefs change, your knowledge about the world changes through your experiences—that’s the well, that’s the stuff, right? So it’s like I have an opportunity with a play to “concrete-ize” where I am now in my evolutionary process, in my understanding of life. So the self that I made when I wrote King Hedley II, I’ll remake when I write my next play, because I’m a different person having written that play. You might say “reannouncing the self.”

Do you feel that you’re becoming a larger person with each new thing?

The whole purpose of life, I believe, is to make your spirit brighter and stronger and larger, so that when you go to the other world you’re as bright and as strong a spirit as you have to be in order to deal with whatever is there. When I’m on my deathbed, I want to be able to say that I’m still in the process of learning, but I understand some things and got this much of it, and some I missed, but I’m kind of glad with what I did learn.