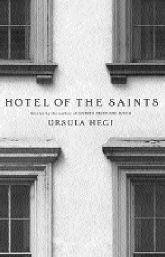

HOTEL OF THE SAINTS by Ursula Hegi (Simon & Schuster, $23)

A DYING dog, a pair of doves, a woman’s perfume, the first moon walk—such are the devices that Ursula Hegi employs to underscore isolation in the workmanlike, deceptively light stories of Hotel of the Saints. These are tales of ordinary people leading ordinary, attenuated lives when a pivotal change crystallizes their estrangement from society, from relatives, sometimes from themselves; they’re left to forge an uneasy peace with a sorrow-tinged existence.

Absence and loss are prominent here. In “The Juggler,” a woman’s grown daughter brings home her new lover, a man who’s losing his sight; the mother’s anxiety about her child caring for this soon-to-be-blind man quickly leads to conflict about the nature of their own mother/daughter relationship. The question of what it means to rely on another too much still hangs in the air as the daughter leaves again, the single mother left to wrest meaning out of the visit in isolation. In “For Their Own Survival,” a man revisits the site of a vacation he took with his wife as he struggles with why she left him; her absence is weighty, and he is completely unmoored until catching and releasing a fish symbolically (and terribly tidily) brings him full circle.

Those who do not find a strange comfort in solitude here carve lives out of unconventional relationships. Lenny, a discontented seminarian, goes to the aid of his Aunt Jocelyn, who has long been on medication of an uncertain nature—she’s too delicate to even use the phone; together they find the wherewithal to give her newly inherited Hotel of the Saints an unusual overhaul, forging a new, shared life in the process. The woman with the dying dog in “Lower Crossing” comes to realize that her life—bounded by trips to the local cafe, working in her plant shop, living with her also middle-aged sister, and occasionally picking up men at the hardware store for sex—is sort of a full one, or must be made to be so, as her best friend slips away from her.

AT ITS BEST, Hegi’s writing has the truth of simplicity; in “Hotel of the Saints,” for instance, Lenny “begins with the renovation, starting in the last room down the hall. Soon, his eyes ache from the relentless gray, and his arms feel heavy. . . . He wishes he could accept everything about the Jesuits. Or nothing. . . . Yet, whenever he pictures himself leaving the order, he gets sweaty and afraid that his faith is not strong enough to stand on its own. . . . ” Another passage, from “Freitod,” brilliantly encapsulates the “tragic, unrequited” nature of parental love. But often a sense of humor goes missing in these perverse paeans to alienation, one that the characters and the stories need to be fully fleshed out, less static, more memorable.

Last lines in this volume also suffer from a ponderousness, providing a more pat and self-conscious closure than the stories need or deserve. In “Doves,” for instance, a quiet, lonely single woman finds herself in a country bar; in the end, “A lean-hipped man asks her to dance, and as she sways in his arms on the floor that’s spun of sawdust and boot prints, she becomes the woman in every song that the men on the platform sing: the woman who leaves them; the woman who keeps breaking their hearts.” Lenny has a similarly excessive revelation at the end of his tale: “For an instant there, it feels as though the ground were tilting beneath him—a seesaw kind of tilting—and as he instinctively braces it with his body, Lenny knows this is the kind of tilting that may happen to you again, and all you have is your faith that each time your body will find some new balance.” With more faith in the reader, Hegi’s fine work would also find some new balance.