SPIRITUALIZED, DJ ASHLEY WHALES

Showbox, 628-3151, $16.50 adv. / $19 8 p.m. Tue., Nov. 6

IN NEW YORK CITY, miles and miles of skyscrapers stand at erect attention like a battalion of obedient glass-and-iron soldiers. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, a tunnel of wind will gather on one of the avenues and send a slight stream of relief along with the flow of traffic. But for the most part, the air—bitter cold in the winter and cripplingly hot in the summer—gets trapped in small spaces much in the same way New Yorkers, living hand-to-mouth and at the mercy of the last stop on the D train, get trapped within the five boroughs. There’s no getting out, nowhere to go, and no way of getting there even if there were.

In the balmy cage of July 1997, two records preached the beauty of open air. The first was Radiohead’s OK Computer, a record so vast, cinematic, and sweepingly inculcating that you couldn’t help but confront your own hopes and fears about information, alienation, and distrust upon the very first listen. I recall lying very still in my basement bedroom as a rickety old fan did its best, imagining myself as a bland subject in the subterranean alien’s homesick home movies. The second record was Spiritualized’s Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space. Miraculously even more oblique and evocative than OK Computer, Ladies and Gentlemen was a trippy trip into awed wonderment. Beginning with the opening title track, a dizzying round of ache and longing hitched on the line “All I wanted in life’s a little bit of love to take the pain away,” the record suggested unshackled freedom and earnest honesty in an era that seemed to reward only those tethered numbly to newly installed T-1 lines. With its conceptual packaging and drifting, symphonic rock arias, Ladies and Gentlemen released cool, cool air into the hot summer heat.

When, during the winter following those releases, the chance came to see Spiritualized and Radiohead together at Radio City Music Hall, my friends and I gathered wool scarves and pea coats and stood in line for hours, braving the tight frosty air and unscrupulous scalpers, to secure tickets for both shows of the two-night engagement. Two weeks later, with a head full of chemicals both organic and otherwise, I watched as the legendary venue buzzed with celebrities, musicians, and ardent fans.

Like an unashamed clich鬠I sat perched on the edge of my seat as Jason Pierce and crew created a wash of sound. The magical, spookwave-producing hand at the theremin captivated my attention while drummer Damon Reese galloped through drum-fills, taking the pace of each song up a notch with each passing phrase. Pierce’s patient timbre sliced the room’s air like a child’s arm roller coastering out the window of a car. The slide guitar on “Shine a Light,” off the previous year’s Lazer Guided Melodies, meshed with a stunning light show and melted the remaining defenses of all impatient Radiohead fans. By the time Yorke and Co. took the stage, there was nary a shoe ungazed upon, no rock not thrust into space and exalted, no ear unawed by the juxtaposition of jarring riffs and gospel- worthy choirs over symphonic, operatic openness and jazz-inspired movements. The entire set was, in a word, magnificent.

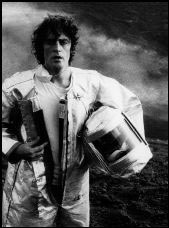

The recently released Let It Come Down marks the return of J. Spaceman. Ever insistent that he is as inspired and informed by bands like the Cramps as he is by bluesman Robert Johnson or any postmodern composer, Jason Pierce continues to push and punch at the confines of rock and roll. Let It Come Down was created with the idea that it would be executed live by no less than a 17-piece orchestra. (Several songs were recorded with a full orchestra.) Pierce wrote all 11 songs—each containing numerous elements and movements. Remarkably, this sprawling and expansive release can be called a solo effort. Let It Come Down is the work of one man without anyone’s filters. Though his drug use has been well-publicized (and was, in fact, central to his earlier band’s creative output), and his reputation for being a difficult frontman is an even greater element of the Spaceman 3/Spiritualized lore, there is an almost lighthearted grin present in every hint of seriousness. Double and triple meanings lurk behind psychedelic guitar lines, ironic sarcasm rips at every vocal strain, and it is possible at several precise moments to detect an air of resolute peacefulness in the face of uncertainty. And here, as in New York City or really anywhere these days, an air of peacefulness is a beautiful thing indeed.