VIK MUNIZ: REPARTɍ

Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington 543-2280, $6 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Tues., Wed., Fri.-Sun.; 11 a.m.-8 p.m. Thurs. ends Sun., Dec. 16

THE NEW YORK-BASED artist Vik Muniz, who was born in Brazil, first worked in advertising. Now, after almost two decades of work, he has emerged as an international art star.

Last spring, Muniz had a solo show at Manhattan’s Whitney, and he is featured in the Venice Biennale. His new exhibition at the Henry, “Repart鬢 is one of three concurrent Muniz retrospectives (the others are in New Orleans and Rio de Janeiro). Muniz is also a presence on the Internet; he advises art site www.mixedgreens.com, which is making a documentary on him.

The modern art world has, since the late 1950s, produced celebrities who could appear in Interview as well as ArtForum. But often their personalities prove larger than their talents. Vik Muniz, by contrast, offers a happy synthesis. Although he knows his way around both the media and the academy, his work communicates both inside and out of the art-world context. A Muniz piece can speak to a broad audience very directly.

In 1984, Muniz moved from Brazil to New York. He started making sculpture, then was sidetracked by the process of documenting it. After creating three- dimensional pieces out of wire, he would take their photographs—and then destroy the statues. Muniz liked, he says, “both the mystery and the joke” involved when such reproductions altered the nature of his works.

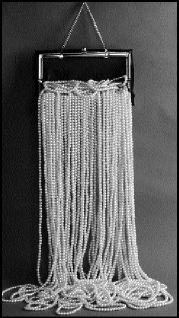

Now he has become both a draftsman and photographer, one who uses familiar—often iconic—images. He transforms these using humble, yet unusual, stuff; Muniz draws with dust, creates with Pantone color chips, paints in syrup. He reinvents a shot of Jackson Pollock at work in viscous Bosco, deepens the angst of Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” with pools of indigo ink.

Viewers are left looking at two things in one: both a photograph and an image they may recognize. Muniz plays with our ideas and memories of art history and with our thoughts about history itself. Are his versions of Tiananmen Square or Brady’s Lincoln really faithful copies of the photos we remember? Or are they just similar drawings Muniz has created, using different twists and perhaps a new perspective?

One thing is clear up front: The works he makes are physically beautiful. Whether his photographed pieces were drawn in dirt or shaped from coils of thread, the results are luscious and deeply sensual. What makes them compelling as art is what they say about change— and the variations that accrue through seeing and making copies.

Because every Muniz is at once a facsimile, a memory, and a string of questions, each makes us ponder what forces shape our observations.

“REPARTɢ DISPLAYS the art along with 19th-century photographs, etchings, prints, and optical toys that Muniz has collected over the years to “document the chronological history of reproduction.” Like his art, however, none of these is what it seems. What looks like an etching turns out to be a photo of one; an “antique” machine for seeing is, in fact, a modern replica.

All underscore the Muniz version of art history, which holds that—despite mechanized reproduction—standardizing images has never stopped the eye from changing them. Like Werner Heisenberg, the guru of quantum mechanics, Muniz believes that every look at an image changes it. “Heisenberg proved that perception alters phenomena,” he says; “that every time you see the same picture, you’re seeing a different one. That’s what my work is about.”

This ambitious show about context suffers from a contextual lapse, however. When “Repart颠premiered in Atlanta, the Muniz works were hung on tall white walls; a separate deep-red room was built in the center of the gallery to house the artist’s own collection of artifacts. But the Henry has scrambled those artifacts in among the Muniz works, often making a viewer assume—incorrectly—that a given piece or pieces acted as direct inspiration. This approach also crowds the large Muniz pieces, which require adequate viewing distance to appreciate.

Six other pictures in the exhibit have a different problem. These are portraits—in sugar—of Caribbean children whose families work in the fields cutting sugar cane. From a distance, they are smiling black faces; closely viewed, each exudes individual charm. A wall text explains the motive behind “Sugar Children”: to contrast the “sweetness” of such innocent youth with the bitterness awaiting them with age.

From a UNICEF-active artist who is committed to helping children, this is clearly a work of good intentions. But the sugar trade is one of the world’s most notorious; it has given us racial inequities, vast corruption, colonial tyranny. Can one sense that kind of subtext in six modest portraits? Using sugar to draw black children caught in its web presumes that we will. Despite the loveliness here, the parable is far too simplistic.