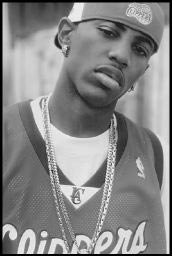

FABOLOUS

Ghetto Fabolous (Desert Storm/Elektra)

Twenty-plus years of hip-hop evolution—a steady, sometimes seismic process of natural selection—and at the beginning of rap’s third decade, out pops Fabolous, the ber MC who’s got a little bit of everybody in him but still miraculously sums up to a whole lot of nothing

As a counterpoint to Fab’s financial success—his album debuted at no. 4 on the Billboard chart during the week of the terrorist attacks—it’s worthwhile to enumerate the things, both tangible and intangible, that the 21-year-old sudden star lacks. First of all, for an MTV-friendly rapper, Fab ain’t easy on the eyes. The inside of his CD booklet finds him track-suited and in various states of snarl, though he does sport female-friendly high cheekbones (more on that later). He’s got a chipped tooth, and that ain’t cute unless you’re Jewel. And considering the alleged maturity of his rhymes, Fabolous on the whole looks like a lanky JV basketball player who’s just now coming off the bench.

And those rhymes are another thing altogether. Give Fab credit for coming this far by standing on the shoulders of giants. He raps like a well-trained machine that’s been programmed with the flows of a hundred MCs and distills them into one metastyle that references them all and somehow sounds like them all, as well (though he sounds like no one more than he does like Mase, the one time Bad Boy shill who watched Biggie die, promptly found God and got the hell out of hip-hop Dodge. He had chipmunk cheeks, too).

It’s that instant recognizability, though, that’s allowed Fab to leap from obscurity to pop rotation in a near instant. You listen to Fab and you swear you’ve heard him before, so comfortable, effortless and easy is his flow. Less than a year ago, Fab was weaseling his way onto DJ Clue tapes. Now, he’s the first artist released on Clue’s Desert Storm imprint. He has, as Biggie Smalls once put it, gone from ashy to classy in no time flat.

So of course he would name his album Ghetto Fabolous, because what other title could truly represent his unexpected, or is that inexplicable, rise? Predictably, his debut teems with paeans to ice and brain—diamonds and fellatio—that do little to add to rap’s long fascination with those subjects (though referring to diamonds as “O’Shea Jacksons” merits a congratulatory pat) but indicate that he’s content to play the seasoned vet, even though he himself is little more than a bagman.

Such obsessions aren’t necessarily rookie mistakes. Rather, the glaring things on Ghetto Fabolous are not those that appear en masse, but those that appear in twos. Two lyrical references to New Jack City. Two bites of Junior Mafia: reinterpolating the hook of “Player’s Anthem” and revisiting the Lisa Lisa-inspired hook of “Need You Tonight.” Two uncredited bonus tracks. Two mentions of his purported ability to acquire select Nikes months before commercial release. In each of these cases, the fragile seams that hold together an album, especially one pulled together so quickly, come undone. It’s as if, in a hurry to complete yet another track, Fab forgot what he did on the previous ones. Laid side by side, their frailties are exposed.

So why does Fabolous still compel? A careful listen to his stunning first single, “Can’t Deny It,” bears all the disappointment of Geraldo Rivera’s Capone vault fiasco. Propelled by Rick Rock’s post-G-funk pop and Nate Dogg’s incomparable hooks, Fab sounds magnificent, but only musters the barest of clever rhymes. He’s partial to two-syllable rhymes, and his sense of timing allows him to impart wit without actually possessing it: “The kid pull the four out a little quicker. You might end up the reason your homies will have to pour out a little liquor”; “It’s nuthin’ but a g thing, I thought you knew/And I’m ’bout to do the numbers that they thought you’d do.”

If it’s possible, Fabolous may well be the first rapper in history to have so thoroughly inculcated the lessons of his forebears that his tendency toward the dispassionate isn’t a liability. On “Ryde For This,” he threatens to “leave niggas on the ground, like tire prints,” but he’s more interested in the punch line and cadence than the sentiment itself. It’s all refined posture, lyrical autopilot. So honed, Fabolous ends up nihilistic but not angry. Slick but not horny. Breathing but not alive.