WILL THE REAL monorail opponents please stand up?

So far, monorail is proving to be—and we do not make this statement lightly—the single most boring major story of the year. Everyone—from former monorail opponent Paul Schell to Sound Transit boosters like transportation consultant Roger Pence—has gotten behind the quirky, once-embattled elevated transit system, which would run from Ballard to West Seattle. At a press conference last Tuesday, Schell (who last year helped persuade Sound Transit to withdraw a $50,000 grant to the Elevated Transportation Company, the group behind the monorail proposal) stood before the press, God, and everybody and said that based on his three-year Seattle Transit Study, “elevated transit appears to be one of the best ways to link downtown, Ballard, and Northgate”—and potentially the best way of moving commuters from West Seattle to downtown as well. Why? It’s all in the numbers: According to the study, monorail would be faster and have higher ridership than either streetcars or buses, two other local transit options the study considered.

Ignoring the timing of Schell’s deathbed conversion (two days after one poll showed monorail supporter Greg Nickels scooting ahead of Schell by six points in the mayoral race), the moment was nonetheless a watershed. Suddenly, monorail seemed respectable.

What happened? No one can deny that much of monorail’s enduring support can be attributed to a growing collective rage against Sound Transit, whose overstudied, overbudget light rail won’t even start being built, even under the most optimistic predictions, until 2009. People are unhappy with the routes, unhappy with the technology, and—most importantly—unhappy with the cost, which, for the original 24-mile route from the U District to Sea-Tac rose $1 billion higher than estimates predicted before Sound Transit decided to go back to the drawing board.

All of which should serve as a warning to monorail boosters, who’ve managed so far to gloss over concerns about view corridors, costs, and potential disruptions to homes and businesses by pointing out that, so far at least, nothing’s certain: not the technology, which could look much like the existing monorail downtown or something sleeker and completely different; not the cost, though estimates released by Schell’s office as part of his study range between $79 million and $82 million a mile; and not the routes, which still form a spiderweb of possibilities on monorail proponents’ map.

Of all the concerns facing monorail supporters, funding is the most problematic. Though supporters hope to secure state and federal funds, those are, according to ETC Executive Director Harold Robertson, at least a couple of years off—and considering the trouble the state Legislature has had getting any transportation proposal through, the prospect for monorail funding “looks pretty bleak” at the state level, Robertson says. That leaves local dollars; currently, monorail proponents are looking at the possibility of redirecting existing taxes or dedicating a new tax, such as a parking tax, to monorail. Initiative 53, the monorail proposal approved by voters in November 2000, set aside $125 million in bonding capacity for the monorail; that money would come from property taxes, which would have to be redirected or increased. Any bond money above that amount would have to be approved by 60 percent of Seattle voters, or about three percent more than voted for Initiative 53, which gave monorail proponents $6 million to come up with a proposal by August 2002. And that, says the still skeptical Pence, “is going to be a huge, huge hurdle.”

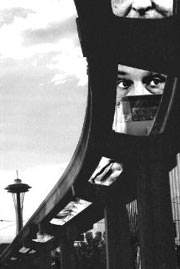

Views are another issue. As monorail supporters pointed out on a recent tour of potential routes from Ballard to West Seattle, the views from the monorail are terrific. And, when you consider that both monorail bridges (across the Ship Canal from Ballard and across the Duwamish to West Seattle) will have to be almost as tall as the Aurora Bridge to accommodate underlying boat traffic, the “view appeal” of monorail becomes apparent.

But what about curb appeal? Under the most likely technology, the columns supporting a monorail system would be at least 16 feet wide at the top. And the trains themselves, while not as obtrusive as elevated light rail or streetcars, wouldn’t exactly be silent—or invisible. “People value their views,” Pence warns. Dan Williams, an architect working with the ETC to flesh out their proposal, brushes that concern aside. “One of the neat things about Seattleites is their relationship to light, and this lets the light shine through, which is very important.”

Public comments, solicited as part of the ongoing Environmental Impact Statement process, indicate that people (those who aren’t just griping about Sound Transit, anyway) are concerned about what the monorail will look like and how it will fit aesthetically into the cityscape. Although everybody loves monorail now, it’s clear that its proponents will have to answer some tough questions—and make some even tougher decisions—before the final proposal comes to a vote in November 2002.