WHY? WHY? WHY?

Consolidated Works, 410 Terry N., 381-3218. $12-$14 8 p.m. and 10:30 p.m. Fri.-Sat ends Sat., June 23

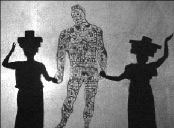

FIRST PIECE of advice: Dress warmly. Second: Don’t wear a short skirt. Third: Drink coffee. Fourth: Come prepared to giggle. All in all, think camp—in the bonfire-and-tent sense, not the Liberace way. It’s chilly in Consolidated Works’ warehouse space, even in the fairly cozy confines of the ample tent raised for Scot Augustson’s latest shadow puppet production. You’re politely asked by a man in a toga to remove your shoes, and then you find a place to recline on the plush coverlets and make your nest of thick pillows. Unfortunately, you can’t just lie back and watch the 80-minute production (though moving does prevent dozing off). To get the 360-degree view (the action is visible on all four walls and the ceiling), you’ll need to turn and flip—hence the short-skirt warning.

The production combines shadows of live actors and puppets that tell Greek myths of debauchery, mayhem, and misery as the narration (done in a variety of amusing, familiar accents) comes from a far corner of the tent. The interaction between the humans and drawings is especially clever and well done. The three Why?’s refer to the agony of Achilles, who’s tormented by the capriciousness of life, death, and love (wait till he finds out about his heel). The gods respond with that answer beloved by parents of toddlers everywhere: “Just because.” Still, the stories of tongues hacked, livers pecked, and lovers turned into cattle are entertaining in a “and did you hear the one about the . . .” kind of way. Audrey van Buskirk

CITIES: CONVERSATIONS IN THE COURT OF KHAN

On the Boards, 100 W. Roy, 217-9888. $16-$18 8 p.m. Thurs.-Sun ends Sun., June 24

THE SIGNIFICANCE of Marco Polo, it might be argued, isn’t that he journeyed to China, but that he came back to Venice, widening the world with his fantastic tales of that faraway land. The always daring UMO Ensemble reworks Italo Calvino’s novel, Invisible Cities, in which Polo entertains Kublai Khan with stories of the places he claims to have visited during his 17-year service, such as the City of Desire and the City of Courage. To call it an adaptation would not be accurate. It’s more of a riff, forsaking Calvino’s text for author Martha Enson’s abstract approach, and UMO’s trademark hybrid of circus acrobatics and modern dance. The result is an enchanting if sometimes perplexing evening that explores the nature of cities and the meaning of home.

To make the material more stage-worthy, Enson invents the Remnants, a set of four fallen amnesiac angels who, in their quest to return to heaven, help Polo realize the cities he describes. To an enveloping live musical score by Amy Denio, these helpers writhe, pantomime, walk tightropes, hang on bungees, tango, trapeze, sing, and ululate to help the story along.

The relationship between Polo and the Khan deepens with each tale, and the Remnants grow ever more frustrated with their banishment. This split may be the work’s chief weakness: It’s uncertain whose story is being told. Nevertheless, the effect is exotic and riveting, even when it sails past without comprehension. Like Polo’s fanciful cities, mere words can’t capture the sad, vicious beauty; you have to go see it for yourself. Gianni Truzzi

DINNER WITH FRIENDS

A Contemporary Theatre, 700 Union, 292-7676. $10-$42 7 p.m. Sun. and Tues.-Thurs.; 8 p.m. Fri.-Sat.; 2 p.m. matinees select Sat.-Sun. and Thurs., June 14 ends Sun., July 1

TOM (Mark Chamberlin) just left his 12-year marriage to Beth (Kristin Flanders) for a more exciting affair with a travel agent, a fact that disturbs the upper-middle-class comfort of Gabe (John Procaccino) and his pristine wife Karen (Janet Zarish), supposedly cozy companions to the couple. Donald Margulies’ Pulitzer-winning Dinner with Friends looks at the fallout and finds that there is more than meets the eye in most romantic commitments.

This isn’t new territory, and the dark humor it inspires (it is very funny) has been handled many times before with far more cutting results. But Margulies distinguishes himself with benevolence; he’s genuinely worried about these people. You could fault his decision to stack the deck against Tom, who seems too irredeemably the weak chump (Chamberlin, however, is dead-on). This production also has bouts of excessive spotlessness—some of the attempts at reproducing the ebb and flow of natural conversation are squeaky-clean—but director Gordon Edelstein is expert at mining the messy silences crouching in everyday chitchat, and his cast is ideal (Zarish’s vulnerability is revealed with particular craft). Beneath the perfect bedsheets of this polished play is a shuddering, humane consideration of how scary it is simply to love and be alive in a world full of necessary ambiguities. That we cling to each other in the gray areas of our mutual fear is captured here with true class. Steve Wiecking

PORCELAIN

Northwest Asian American Theatre, 409 Seventh S., 325-6500. $12 7:30 p.m. Thurs.-Sat.; 4 p.m. Sun. ends Sun., July 1

WRITTEN BY NWAAT’s new artistic director Chay Yew, Porcelain tells the story of John Lee (Ray Tagavilla), a young Asian man who murders his white lover in a public washroom in London. The production relies strictly on a black-clad chorus of four actors (Gavin Cummins, Brandon Whitehead, Conor Duffy, and P. Adam Walsh) to create the multi-faceted and -accented strata of British laborers, policemen, and professionals who comment on the crime.

The four-man tag team has quite a challenge, which director Valerie Curtis Newton has assured is met with passionate restraint. Cummins gets stuck with a bunk role as the stereotypical psychologist assigned to the case—he’s given hoary dramatic clinkers like “I want the truth!”—but he’s quite convincing as other London denizens, as are the rest of the chameleonic ensemble (Whitehead even pulls off a difficult turn as Lee’s father, and Walsh is dynamic as Lee’s brutish beloved).

Though the inherent racial issues aren’t explored with enough subtlety (there’s a clunky dependence on the word “chink”), Yew is devastatingly accurate with the slippery hatred and hypocrisy found in any public discussion of gay sexuality. The play has a crisp intelligence that never becomes aloof, furthered here by Newton’s elegant compassion and the anchor of Tagavilla’s performance. He’s very good, steely and smirking yet still able to communicate the ache for intimacy that Lee’s lavatory prowlings (the “marriage of dirt and desire”) illustrate with such raw tenderness. He spends the play surrounded by squares of red paper that he is methodically folding into origami swans. By evening’s end, it seems as though he’s making something memorable out of blood—a graceful, brutal task that Yew’s play, and this fine production, also accomplishes. Steve Wiecking

GREAT MEN OF SCIENCE, NOS. 21 & 22

The Empty Space Theatre, 3509 Fremont N., 547-7500. $18-$28 7:30 p.m. Sun. and Tues.-Thurs.; 8 p.m. Fri.-Sat.; 2 p.m. matinees select Sat.-Sun ends Sun., July 15

WHEN ACTOR Burton Curtis, an always reliable source of local comic revelation, seems at a loss, something is amiss. Playing Jacques de Vaucanson, an impassioned 18th-century inventor intent on proving the idea that “nothing is random” by building a mechanical duck, Curtis is oddly removed throughout Glen Berger’s charming Great Men of Science, Nos. 21 & 22. The intentionally thick lingo that Berger uses to both gently mock and celebrate grand human achievement is awfully sticky on Curtis’ tongue, and as the rest of the entertaining, lopsided evening runs its course it’s clear that he couldn’t help it: The production is suffering from a schizophrenia that must have left him puzzled.

Berger sees the inventor’s experience, and that of Lazzaro Spallanzani (Eric Ray Anderson), who later in the century (and in the play’s second act) attempts a heroically ludicrous experiment mating frogs, as courageous folly. He’s admiring the strength it takes to bend life to one’s will, while simultaneously grieving and laughing at the obvious human discoveries that are missed along the way.

Dan Fields’ production is comfortable with either grieving or laughing, but doesn’t quite grasp how to achieve both at the same time. The first act with de Vaucanson has an eccentric appeal, yet seems stilted and unsure of just how funny it’s supposed to be, while the production’s concluding section is built on guffaws and little else. The show is blessed with a fine cyclorama set by Louisa Thompson and two perfectly ripe comic turns by Anderson and, as his love-struck housekeeper, Lori Larsen; Larsen, don’t get me wrong, has enough to serve as an intelligent distraction. Taken as a whole, however, Great Men is as messily ambitious as its protagonists. Steve Wiecking