WEEKEND

written and directed by Jean-Luc Godard with Mireille Darc and Jean Yanne runs May 25-31 at Grand Illusion

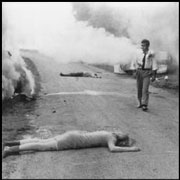

WHAT MOST REMEMBER about Weekend is the famous traffic jam with its seemingly unending tracking shot down the line of cars (horns blaring triumphantly), its occupants’ funny antics, and their indifference to the corpses and flames. Roland and Corrine are driving to the country to visit—and poison—her parents, hoping to collect on the will. Reminiscent of Ionesco or Bu�, Weekend‘s an avant-garde twist on the road movie in a brutal, hellion world of mad materialism, where people wave guns at the least provocation. It definitely isn’t a popcorn flick or a date film.

While critics laud Jean-Luc Godard for his creative excitement during the French New Wave, most people find him challenging at best, and more likely baffling, irritating, and offensive. Here, one might grasp the metaphor of Marxist hippie cannibals (at least as Godard indicates it’s a metaphor), but what are we to make of the dull, spinning camera that shows nothing of interest? Or the static shot of one workman while a second speaks his thoughts off-screen?

In an early scene that seems deceptively out of place, Corrine, curled in bra and panties, makes an engrossing erotic confession to fully clothed Roland—quelle Fran硩s!—of her sexual domination by another couple. She speaks flatly; he listens distantly. We’re drawn in, and we squirm. Yet two later sentences leave us tottering, unsure if the event was real.

Of course it’s not real, Godard says, it’s a film. Repeatedly, we hear his dissatisfaction with the medium he once boasted could convey “the truth 24 times a second.” When the couple tries to hitch a ride, Roland asks each driver if they are real or a film character. To the latter, he snarls, “No, you lie too much.” He sets one character ablaze—no matter, he shrugs, she was fictional. Then Godard unflinchingly shows us the very real slaughter of a pig, as if to ask, “Do you prefer it?”

It’s easier to recognize Godard’s crisis of faith in hindsight now that we know this as his last energetic work before 18 years of cinema atheism. (1985 marks his next interesting effort, Hail Mary.) To those who chafe at auteurist arrogance, his shaken belief may appear to be rough justice. But the impact this 1967 film still has suggests that Godard was right about the power of cinema in the first place. The muddled, perplexing, outrageous, maddening, brilliant, stumbling Weekend still provokes. Its daring brings our speeding attention to a standstill.