SIMON MAGUS

written and directed by Ben Hopkins with Noah Taylor, Ian Holm, and Rutger Hauer runs May 11-17 at Varsity

CAUGHT AT THE CROSSROADS of magic and realism, Simon Magus unfolds like a Yiddish folk tale, yet it’s inspired by a minor New Testament parable and laced with Shakespearean intrigues and gothic stylings. A morally hefty comedy, it pits Jews against Christians as both groups battle for the soul of the titular half-wit in whose grimy hands lies the economic fate of his dying village. If all that sounds confusing, it is. The debut of director/screenwriter Ben Hopkins is an ambitious mess—an atmospheric allegory in which the story is far less compelling that the cinematography.

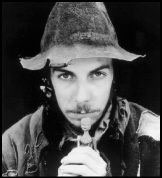

In Hopkins’ gloomy vision of 19th-century Poland, the eponymous Simon (Shine‘s Noah Taylor) is a scapegoated outcast and suspected sorcerer—an object of fear and loathing among his superstitious people, who refuse to let him pray in their temple. He’s visited by the Devil (Ian Holm), whose provocations force Simon to abandon his faith and convert to Christianity. Holm’s spooky appearances, brief as they are, are the only sharp, unambivalent moments in the film.

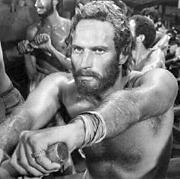

Simon’s religious betrayal makes him a pawn in a landgrab between a young Jewish scholar (Stuart Townsend) and a racist businessman caricature (Sean McGinley), both of whom appeal to the local squire and poet (Rutger Hauer) for justice. A pair of cursory love stories adds even more to the mix (too much, in fact), which Hopkins can’t hold together. The actors themselves seem to have different ideas about what they’re doing. Taylor’s almost too comically inspired to shoulder the fable’s moralism, while a Goethe-spouting Hauer struggles mightily with Hopkins’ stilted, quasi-archaic language.

Simon‘s visual power nearly salvages its contextual collisions, embodying precisely what Hopkins can’t state clearly. Misty, muted landscapes and crude architecture evoke a society of superstition, where monsters could lurk in the shadows or spring from the muddy earth itself (both of which they do). Lingering images, though, can’t provide cohesion, movement, or a deeper spirituality to a film that, at its core, lacks essential unity.

The one time the ragged Simon gels is during its climax: a creative use of the medieval Jewish blood libel. (That myth of Jews killing and eating Christian babies was a common pretext for anti-Semitic violence.) Unfortunately, the scene still carries the offensive, implicit connotation that Christians are evil. That’s not Hopkins’ intent, of course, but with an excess of elements working at cross-purposes, his mythic ambitions remain garbled. He’s nailed the darkness at the heart of our most cherished fairy tales; he would have done better to recall their deceptive simplicity as well.