DRUNK ON ADRENALINE, the publishing industry has but a few criteria for its newest class of best-selling nonfiction authors. One, be brave. Two, overcome adversity. Three, travel to remote, dangerous places. Four, come back not unscathed and not unchanged, since readers are not interested in a concomitant lack of personal growth. Fifth (and this is optional but desirable in the marketing of said tome), could someone in your party preferably die on your adventure so that we might extract a valuable lesson from their demise? (Your crying would also help in this regard.)

Touch the top of the world

by Erik Weihenmayer (Dutton, $23.95)

Along the Inca Road

by Karin Muller (National Geographic Adventure Press, $26)

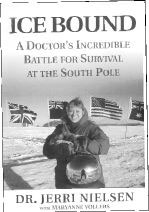

Icebound

by Dr. Jerri Nielsen (Hyperion/Talk Miramax Books, $23.95)

Quest for adventure

by Chris Bonington (National Geographic Adventure Press, $35)

That’s not too much to ask, is it? Hey, we’re not even bothering with a thesis or rudimentary grasp of style! Certainly not since Into Thin Air, which surpassed those standards and spawned dozens of imitators of far less merit. In this light—at this altitude?—a foot-high stack of four exotic adventure books reveals as much about readers’ appetites as it does about the exploits detailed within.

In blind mountaineer Erik Weihenmayer’s admirable Touch the Top of the World, we’re thus treated to both his alpine exploits and family woes, which began a generation back on his mother’s side. She grew up poor, Southern, and unhappy, we learn, but still recovered herself in a second marriage, which produced a son with a congenital eye defect that would leave him legally blind by age 14. Worse lies ahead. How does our hero cope? After a period of adolescent rebellion, he discovers climbing and, with it, the heady rush of publicity that only sponsored mountain climbing can produce. The summits of Rainier, Kilimanjaro, McKinley, and Aconcagua topple to his feet. He even scales the storied multi-day Nose route on Yosemite’s El Capitan, producing a peak-bagging list that many sighted climbers would envy.

IN THE EXPANSIVE view of Karin Muller (Along the Inca Road), sponsorship by the National Geographic Society allows her to plan an itinerary that’s Packed. With. Color. Her breathless narrative style is accordingly Guaranteed. To. Annoy. Pick a festival, any festival, along her route and she’ll eat or drink what’s handed her (dysentery? ha!), dance with the locals, protest their government, plow their fields, and carry their 200-pound sacrificial pigs. (Anything for a story, particularly since she’s accompanied by a cameraman to chronicle her exploits.) The book’s sub- title, A Woman’s Journey into an Ancient Empire, explains the historical digressions (tolerable) and reiterates that Inca Road is presumably worth reading because it’s By. A. Woman. (After trekking some of the same route, Weihenmayer’s account is mercifully short and lacking in detail by comparison; it shows the value of occasionally closing your eyes and field journal.)

Ripped from the headlines, Dr. Jerri Nielsen’s Icebound basically expands her 1999 ordeal as the sole doctor and sole breast cancer patient at McMurdo Station, Antarctica. Then front-page news in The New York Times, the story is fleshed out but familiar (especially after being televised on ABC’s Prime Time this January), detailing her self- diagnosis, self-biopsy procedure, self-administered chemotherapy, and eventual airlift evacuation. Fortunately, her postscript notes, treatment seems to have been successful—although at the cost of her becoming a reluctant object of media scrutiny, she says. (While you can understand why Nielsen fled an abusive marriage for the South Pole, that doesn’t excuse a book mostly made up of reprinted e-mail.)

By contrast, the second edition of Sir Chris Bonington’s Quest for Adventure concerns those who willfully seek out perilous situations, usually calculating fame as part of the bargain. He’s added a few new stories since the book’s original 1981 publication, which emphasizes its anthology nature. It’s a collection, not a sustained narrative, offering snapshots—of a fairly high quality—from Everest, the Blue Nile, the polar regions, the seas, and El Cap again (you remember, the one the blind guy climbed). There’s nothing new, but thankfully, being British, Bonington mostly abstains from the touchy-feely stuff. Men climb, die, shed a few tears, then move on. (Mountaineers will chiefly appreciate the account of a brutal ascent up the north face of Changabang from ’97.)

SO WHY BOTHER? (The adventures, we mean, not the books, which you’re free to read at your leisure.) Why go, and why write about it afterwards? If you solo a peak in some remote wilderness, unobserved by anyone, doesn’t the feat exist? Are these volumes about self-validation, self-aggrandizement, or pure publicity?

Or are they really about us and our perceived needs? Do we, Walter Mitty- like, fuel the progressively wilder and more whacked-out excursions of these intrepid authors only because of our own supposedly thwarted, cubicle-dwelling lives? We read the books, watch the appearances on Oprah, buy the tickets to the slide shows and motivational speeches, but do we really absorb the uplifting messages into the fabric of our own quotidian lives?

So the next time you’re slogging up Mt. Si (Girl Scouts and golden retrievers blithely bounding past you), ask yourself how much of the “follow your bliss” stuff makes the trail any less muddy, the skies any less wet, the picnic spots any easier to find on top? How much book-learned endurance and stoicism did you really need to reach the bloblike summit? Surveying majestic North Bend—home to mighty outlet malls!–from this sublime perspective, you’re not likely to recite inspirational passages from these books (or any other).

Instead, as you zip up your Gore-Tex parka against the chilly descent, take consolation from the fact that someone someplace far away is suffering far worse conditions, taking notes, rehearsing anecdotes, preparing their pitch to a literary agent for yet another adventure book that you don’t actually have to read. Then get yourself a pastry in town before turning back onto the freeway.