The pocket of the Blue Ridge Mountains where my parents dwell—and where, consequently, I am spending the holidays—is isolated. Mom and Dad live on a winding country road that has never known streetlights. The nearest neighbors are well out of earshot of even the most bloodcurdling scream. The other morning I awoke to discover the electricity was out and thought of the Donner party.

In a word, it’s spooky out here. No wonder I’ve been seeing ghosts everywhere. Not in the Scooby Doo, floating-sheets-and-clanking-chains sense, but palpable spirits from bygone eras nevertheless.

My parents’ digs serve as a family museum. Each corner showcases artifacts imbued with historical significance, from an antique desk rescued from a one-room schoolhouse to my great-aunt’s lamps, to even the syrup decanter waiting next to my oatmeal. Generations of meticulously dusted knickknacks are evenly spaced on every surface, and black-and-white photos run the length of the main hallway.

Dad’s hobby, genealogy, only heightens my sensation that there are more than three of us here. He’ll settle down to dinner after hours in his study and announce proudly that he’s found Uncle Fred. Who? Then he’ll add, “He’s buried in Fremont, Ohio,” and I’ll realize Dad’s talking about a distant relation who hasn’t drawn breath since the 1800s, as if he just ran into him at the Shell station.

Also haunting the house is the youngster I used to be, which, in Dickensian fashion, I’ve dubbed the Ghost of Kurt Past. My mother may have recently confessed that she’s given up on trying to change me, but she also seems to have overlooked the fact that I’ve changed, period, in the 15 years since I left home. The cupboards are stocked with snacks I haven’t craved since high school. Christmas morning, I unwrap a replacement for a long-lost necklace I wore religiously when I was 13 and have not missed since; catching a glimpse of it later in the bathroom mirror, gleaming in my chest hair, I’m reminded of Boogie Nights.

Desperate for a respite from these restless spirits, I visit the sole independent record store of note in the region. Yet ghosts haunt Safe as Milk (20 Kirk Avenue, Roanoke, Va. 24011, 540-982-7789) too. Flipping through the used vinyl bins, I am unnerved by how many of these platters were recorded by artists who died in 2000: Ian Dury; “Philosopher of Soul” Johnnie Taylor; Vicki Sue Robinson.

I’ve never come across a solo single by Benjamin Orr of the Cars in my hunting before, but today I find several. Despite years of disdain for Foghat, I get misty thinking about poor dead “Lonesome” Dave Peverett. Still reeling from the fact that Kirsty MacColl, Roebuck “Pops” Staples, and guitarist Rob Buck of 10,000 Maniacs all passed away within hours of each other a couple of weeks ago, every piece of wax I pick up represents another reminder of my fleeting mortality.

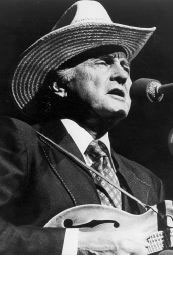

And then I recall a moment I’d all but glossed over the day before. My brother had driven out to visit. At a loss for music I could play that wasn’t another one of Dad’s blasted Christmas choral collections yet wouldn’t drive my parents into conniptions (i.e., anything in my CD wallet), I’d popped in The Music of Bill Monroe (MCA), a four-CD anthology celebrating the bluegrass great, which I’d given my father for Christmas in 1996, the year Monroe died.

I’d always assumed that, like every other record I’ve given Dad, from the Charles Ives string quartets to the Henry Mancini collection, the Monroe set had remained neglected in the darkest recesses of the stereo cabinet since he unwrapped it. Maybe it has. Regardless, my father sat there, singing along with song after song: “In the Pines,” “Footprints in the Snow.” His familiarity with the hokey “Y’all Come” left me embarrassed yet transfixed, like stumbling across Hee Haw while channel surfing.

In between tracks (and sips of Chivas Regal), my normally reticent dad told my brother and me tales we’d never heard before: of his mother inflating family insurance rates by wrecking their only car, three times, on the same hairpin curve; of entertaining college classmates by playing banjo at parties; and how, when he dies, I will inherit a 1-square-foot plot of Tennessee real estate bequeathed to his hard-drinking father (my grandfather), as part of a long-forgotten Jack Daniels promotion.

Often when I’m listening to old records, I’m reminded of friends no longer shaking their groove things on this mortal coil. Songs conjure up a lot more spirits than lamps or syrup decanters, but those ghosts rarely startle me because I take them for granted. Now the music of Bill Monroe will forever summon memories of that rare hour with my father at his animated best.

I knew there had to be a friendly ghost kicking around these mountains somewhere.